The job is killing them: Family lawyers experience threats, violence

Photo illustration by Sara Wadford, Ivan Smuk, Daxiao Productions, Anastasiya Aleksandrenko, Silvabom, Olaf Naami/Shutterstock.com

After lawyer Sara Quirt Sann was murdered at work, her husband evoked Ephesians 6:10-20, a Bible passage about the armor of God, to describe her.

“She had to put her armor on every day and fight for those who needed representation,” Scott Sann wrote on Facebook. “Make no doubt in your mind that she was a warrior.”

Sann, 43, was a solo lawyer, and she did a lot of guardian ad litem and family law work in Wausau, Wisconsin. In early 2017, that included representing Naly Vang in her divorce from Nengmy Vang. It wasn’t going smoothly; Nengmy Vang was pressuring his wife to speed up the process by using a traditional Hmong divorce, in which their clan elders split their property and custody of their seven children. But Naly thought the American court process would better protect her.

It all came to a head on March 22, 2017, when Nengmy stormed into the bank where Naly worked and demanded that she sign divorce papers that didn’t exist. Two of Naly’s colleagues hustled her out the back door—and Nengmy shot them. He then drove to the law firm Tlusty, Kennedy & Dirks, where Sann rented an office, and forced an employee at gunpoint to show him where Sann worked. That employee told the police she then heard a scream, two gunshots and the sound of someone running down the stairs. Nengmy would go on to kill a police officer before officers fatally shot him.

The murders shook up Wausau, a central Wisconsin city of about 40,000 that just a year earlier the FBI had called one of the safest metro areas in the Midwest.

“It was just such a shock,” says Pam VanOoyen, a friend of Sann’s and a judicial coordinator for a Marathon County judge. “We’re not as big as Green Bay or Milwaukee or Madison, even, for that matter. And so we’re all really connected.”

In response, citizens formed Wausau Metro Strong to build a safer community. Among its projects was Sara’s Law, a measure that makes the penalties for battery or threats to a family lawyer a low-level felony, as it would be for battering a police officer or a judge. In most other circumstances, battery must cause great bodily harm to carry the same penalties. The bill passed the state legislature easily; Wisconsin Gov. Scott Walker signed it April 11 in a courtroom named for Sann.

Attorney Jessica Tlusty—who runs the firm that rented Sann her office—helped lead the Sara’s Law effort. She says the law grew out of Scott Sann’s wish that his wife had better protection. Tlusty practices family law herself, and she says threats and violence are too common.

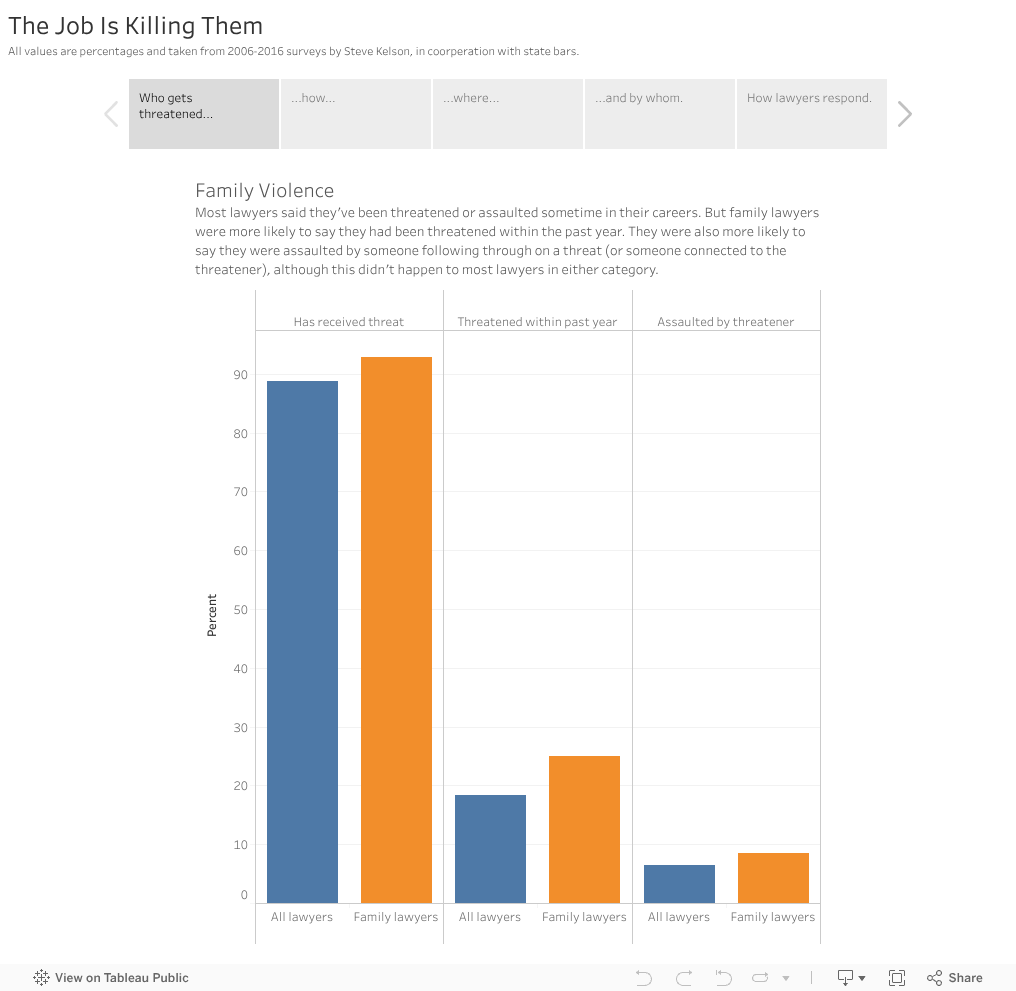

Family lawyers face disproportionate amounts of threats and violence. Charts by Lorelei Laird.

‘It’s the Risk You Take’

A series of surveys on violence against lawyers shows that family lawyers face disproportionate amounts of threats and violence compared to other lawyers. Almost all lawyers in the 27 states surveyed said they’d received some kind of threat or experienced violence. But the rate for family lawyers was higher.

Family lawyers were more likely to have been threatened within the past year and were more likely than lawyers in general to say they were assaulted, especially by someone who had threatened them before. Less than 10 percent of lawyers in both categories said they’d been assaulted.

Steve Kelson: “It seems as though upfront, many people said, ‘Well, it’s part of practice – you need to expect it.’ There’s also kind of an impression ... ‘Yeah, there’s a lot of threats, but nothing will happen about it.’ ” Photo by Busath Photography.

Lawyers have reported receiving threats about their children being raped, having their car tires slashed, and seeing clients shot to death in front of them.

“We are often looked at as the cause of many problems in custody cases because the parties want someone to blame,” Tlusty says. “So threats tend to come toward the attorneys.”

The surveys come from Salt Lake City attorney Steve Kelson, who has a full-time business litigation practice at Christiansen & Jensen. One of his law school professors had said the issue was understudied, and Kelson discovered he was right—no one was tracking it in the United States. He took up the challenge in 2006, surveying Utah State Bar members.

He has since surveyed just fewer than 12,000 lawyers in 27 states, most recently in New Hampshire in 2017. Lawyers generally are recruited by state bar associations to participate voluntarily and anonymously. Kelson provided state-by-state data to the ABA Journal, which used it to compile national numbers.

Those numbers reveal that 88.7 percent of all lawyers responding to the surveys had received some kind of threat or experienced violence. The number of all lawyers who said they’d actually been assaulted was much lower, at 8.6 percent—but 42 percent of lawyers also said they’d experienced an in-person confrontation that fell short of assault, and 6.6 percent said they’d had property damaged.

When responses are broken out by the lawyer’s practice area, family lawyers consistently have higher rates of threats and violence. Kelson says criminal lawyers also reported an above-average rate of threats and violence, as did lawyers choosing “general practice,” which could include many practice areas. This might not come as a surprise for lawyers specializing in criminal cases, whose clients or opposing parties sometimes have a history of violence.

But family lawyers’ work is civil—and 92.8 percent, more than lawyers generally, had experienced some kind of threat or violence. Family lawyers also were more likely to say they’d experienced in-person confrontations, property damage or assault. When they were assaulted, the person responsible was more likely to be someone who already had threatened them (8.5 percent vs. 6.4 percent for all lawyers). About a quarter of family lawyers said they’d been threatened within the past year; only 18.4 percent of all lawyers said that.

Kelson’s surveys suggest most of those threats are coming from opposing parties. While lawyers in general were more likely to say they were threatened or attacked by a client, only 38 percent said they were attacked or threatened by an opposing party. For family lawyers,that rate was a much higher 54.4 percent. It’s a reality for many of the family lawyers who answered Kelson’s surveys.

“As a family law attorney, there have been many times whenI have been confronted in person … and threatened,” a Nevada lawyer wrote in response to Kelson’s 2012 survey. “It seems to come with the type of law I practice.”

“It’s the risk you take when you’re involved in very high-conflict, highly emotional cases,” wrote an Alaska lawyer in 2015 who’d moved away from guardian ad litem work.

Sidebar

Steps to protect against violent clients

While family law practitioners face violence more often than other lawyers, office security and personal safety are important issues for all attorneys. Practicing lawyers and experts in the field of workplace violence have suggestions on how to protect yourself and your practice from a potentially violent client. The following ideas came from interviews with attorneys Steve Kelson, Stephen Zollman, Vivian Huelgo and Allen Bailey; psychologist Stephanie Tabashneck, and safety experts Jimmy Choi and Ian Harris.

Jimmy Choi: In the office, make sure there’s more than one way to get out of every room.

Stephen Zollman: Meet with clients who concern you at the courthouse so that they have to go through security and a bailiff is close by.

Vivian Huelgo: If you’re worried about an opposing party confronting you outside the courthouse, talk to courthouse security about alternative entrances. Ask for an escort (from courthouse security) if you feel you need it. You can sometimes get clerks to drag their feet on paperwork to keep a batterer busy while you leave.

Zollman, Stephanie Tabashneck: Listen to upset clients with sympathy.

Choi: Recognize that it is possible that somebody who is upset enough will try to hurt you.

Choi: Try verbal de-escalation first. This means giving the other person a way to get out of the situation or save face without hurting you. There are scripts in use in some professions that deal with vexatious patients, customers or clients.

Choi: Never watch your phone in a situation you believe is high-risk. Look for escape routes on the street, like businesses open to the public.

Choi: It’s best to avoid getting physical, but if you want to be able to defend yourself, get serious about training. It’s hard to remember complex things under stress.

Tabashneck: One red flag is if someone makes a specific threat that includes a time and a place. Ready access to a gun is also a concern.

Huelgo: With domestic abuse, escalating violence and stalking are both signs of danger. The time right after the abused partner leaves is also, statistically speaking, the most dangerous.

Ian Harris: Secure your computer systems and social media accounts, and talk to your domestic abuse clients about what kind of social media their abusers use.

Huelgo: Think about opportunities to make your office more secure.

Choi: If you carry a gun, it’s most effective when the person you feel is a threat knows you have it. This means it’s more effective in states with widespread concealed carry, and for people who can communicate clearly that they have the gun without escalating the situation.

Allen Bailey: Keep a gun it in a desk drawer, because carrying it could escalate a situation.

Lawyers aren’t the only targets of violent clients. Judges must face the possibility of attacks as well.

Nathan Hall, security consultant for the National Center for State Courts, says the state courts have a wide variety of approaches to security, including a few (generally smaller) with not much security at all. Federal courts, because they are all one system and security is handed over to the U.S. Marshals Service, do better.

All state courts should all have a security plan, with responsible parties on a standing security committee. Courthouse personnel should be trained, and the NCSC does offer training. You don’t need bucketloads of money for some of this.

State courts should have security cameras, keep their shrubbery trimmed and maybe offer call boxes at times when cellphones aren’t available.

Judges should have secure parking, and escorts should be available for judges and parties at risk.