The job is killing them: Family lawyers experience threats, violence

Photo illustration by Sara Wadford, Paola Crash, Andrey_Kuzmin, Silvabom, Ola Naami/Shutterstock.com

The threat isn’t limited to attorneys, either. In Arizona in June, Dwight Jones killed two paralegals, Veleria Sharp and Laura Anderson, who worked for the law firm that represented his ex-wife in their divorce. Authorities believe the ex-wife’s lawyer was the intended target. Jones also killed psychiatrist Stephen Pitt, who had evaluated Jones at the request of the divorce court, as well as three other people, one of whom might have been mistaken for a counselor who had evaluated Jones’ child by court order. Jones ultimately fatally shot himself in a hotel room.

While Jones’ motives remain unknown, acrimony in family law cases can be reason enough for caution, especially when children are involved. California attorney Stephen Zollman’s practice includes representing parents whose children might be taken away from them. Even as a former public defender, he thinks family court carries more risk than criminal court.

“You can take a lot from people, but when you start talking about taking their children … there is no greater loss and greater trigger,” says Zollman, a solo in Guerneville in Sonoma County.

The threat is also elevated for lawyers who represent victims of domestic violence. There, the opposing parties have a history of violence—but they’re less likely than criminal defendants to be locked up. Vivian Huelgo, chief counsel for the ABA Commission on Domestic & Sexual Violence, says they’re also used to having power and control over victims. They might see lawyers as a threat to that control.

“I felt way more threatened and kind of menaced by the batterers ... as a family law attorney than ever in the years that I spent as a prosecutor,” Huelgo says.

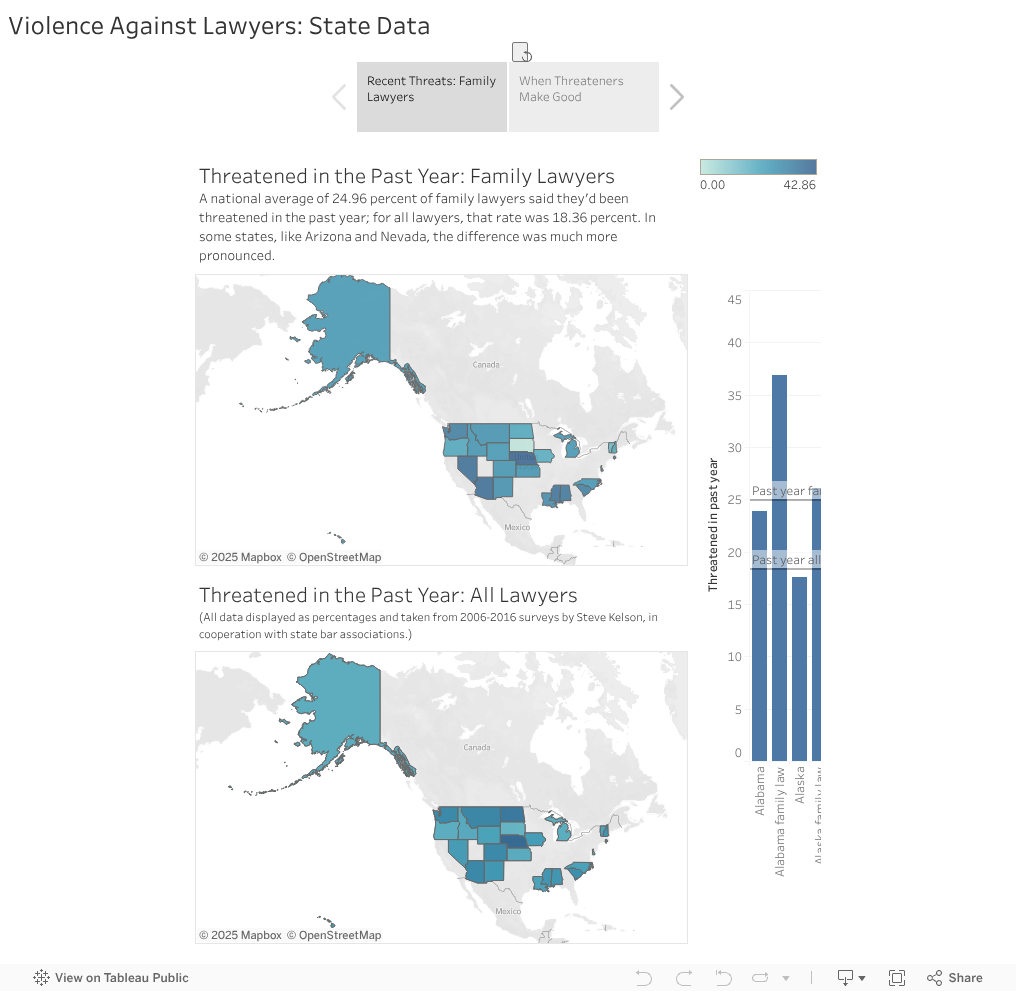

In some states, threats to family lawyers are more pronounced. Charts by Lorelei Laird.

Vexatious Litigants

Despite getting threats, practicing family lawyers say actual violence isn’t frequent—even for people who regularly represent domestic violence victims, such as Allen Bailey of Anchorage, Alaska.

“It’s not a weekly or monthly or annual occurrence,” says Bailey, a solo and the ABA Section of Family Law’s liaison to the Commission on Domestic & Sexual Violence.

But it does happen. Bailey keeps a gun in his desk because of a former client’s ex-husband who he suspects stalked him. The man had stalked the former client, filed a baseless bar complaint against Bailey, and tried to frame him for a financial crime. Bailey has never used the gun, but he has called the police on a few clients’ exes who refused to leave his office.

Comments on Kelson’s surveys suggest some of Bailey’s experiences are common. Family lawyers frequently said angry parties left negative and often-false reviews on lawyer rating websites or social media and sometimes filed frivolous ethics complaints. Confrontations in court or at the office also were widely cited, as were bricks, rocks and bullets through windows.

Survey respondents had some hair-raising stories. An Iowa lawyer wrote in 2013 about receiving a call at home from someone threatening to rape the lawyer’s preschool-age daughter. In Kansas, a lawyer wrote in 2013 about helping a client divide marital property at the home of the client’s estranged husband when he pulled out a gun, threatened the lawyer, killed his wife and then killed himself.

Although many of the survey comments cite male aggressors, there are plenty of stories about women. In the 1990s, a female former client of Bailey’s killed Jim Wolf, an Anchorage municipal prosecutor as well as a friend and former colleague of Bailey’s. Madeline Marzano-Lesnevich, president of the American Academy of Matrimonial Lawyers, says a lawyer at her firm had all four tires slashed by a woman the firm had dropped as a client.

During one divorce case, Marzano-Lesnevich recalls being approached by an opposing counsel in such a threatening way that courthouse personnel intervened. “He was a criminal law attorney who was acting as an attorney for his friend in this arena,” says the founding partner at the Hackensack, New Jersey, firm of Lesnevich, Marzano-Lesnevich, Trigg, O’Cathain & O’Cathain. “I guess he just let his closeness to his friend get the better of him when he was not prevailing.”

Assessing risk

Vivian Huelgo: “I felt way more threatened and kind of menaced by the batterers ... as a family law attorney than ever in the years that I spent as a prosecutor.” Photo courtesy of Fordham University School of Law.

Despite stories such as these, relatively few lawyers seem to be worried about safety. Marzano-Lesnevich says she hasn’t heard it discussed much, even in family law circles. Kelson’s surveys show a majority of lawyers in general don’t change how they practice law in response to threats, although family lawyers are more likely to.

“It seems as though upfront, many people said, ‘Well, it’s part of the practice—you need to expect it,’ ” Kelson says. “There’s also kind of an impression ... ‘Yeah, there’s a lot of threats, but nothing will happen about it.’ ”

That’s a mistake, says Dr. Jimmy Choi of My Occupational Defense, a San Francisco company that provides self-defense training for the workplace. Choi, who sees his share of threats through his work as an emergency room physician, says the first step is to realize a threat can be dangerous. Human beings tend to think everything will stay normal, he says—which can lead people to dismiss the danger.

The ABA domestic violence commission’s standards of practice say safety planning should be used in every domestic violence case. This is mainly for the client’s safety, but it can be useful if there’s a threat to the lawyer. One tool the commission recommends is a questionnaire that assesses danger, created by Johns Hopkins University nursing professor Jacqueline Campbell.

Huelgo says lawyers should look for recent changes or escalation of the violence—more serious injuries, more frequent attacks, attempted strangulation, new abuse of children and pets. Stalking, threats to the victim and threats of suicide also can be red flags. Violence often escalates when the abused partner leaves, she says, because abusers feel their control slipping.

Stephanie Tabashneck, a psychologist who routinely handles child custody evaluations in Boston, performs formal risk assessment in some of her cases. She looks at any past history of violence and the nature of that violence, any mistreatment as a child, the person’s attitudes and beliefs, any substance abuse, and recent changes in the person’s support system. Research shows that being male contributes to risk, she says, as does access to guns.

The details matter. If a threat includes a specific way to do the harm, such as a gun, and a specific time, such as that evening, “that’s a really high risk of violence, and I’d be deeply concerned,” says Tabashneck, who recently graduated from the Northeastern University School of Law.

Huelgo also advises lawyers to determine whether information about them is available to strangers. Lawyers who own houses, for example, might be easy to find through local land records and might consider putting their property into a trust or a business with a different name.

The internet is another place to tighten things up. Ian Harris, technology safety legal manager at the National Network to End Domestic Violence, says angry parties sometimes go on “electronic sprees,” in which they trash the lawyer on every platform they can. They also could hack into the lawyer’s business records, which could lead to unauthorized access to client information.

The best defense is prevention, says Harris, a former family lawyer from New York City who’s now based in Washington, D.C. He suggests lawyers start each case by talking to clients about what platforms their exes use, how they use them and how frequently. This is focused on the client’s safety but also might help identify ways technology can be used against the lawyer.

“If somebody hacks into your account or starts a process of trying to take you down online, it’s hard if you haven’t prepared in advance for that,” he says. “Learning how technology is misused against the client is probably the best opportunity to start thinking about [how] somebody might use it against you.”

Sidebar

Steps to protect against violent clients

While family law practitioners face violence more often than other lawyers, office security and personal safety are important issues for all attorneys. Practicing lawyers and experts in the field of workplace violence have suggestions on how to protect yourself and your practice from a potentially violent client. The following ideas came from interviews with attorneys Steve Kelson, Stephen Zollman, Vivian Huelgo and Allen Bailey; psychologist Stephanie Tabashneck, and safety experts Jimmy Choi and Ian Harris.

Jimmy Choi: In the office, make sure there’s more than one way to get out of every room.

Stephen Zollman: Meet with clients who concern you at the courthouse so that they have to go through security and a bailiff is close by.

Vivian Huelgo: If you’re worried about an opposing party confronting you outside the courthouse, talk to courthouse security about alternative entrances. Ask for an escort (from courthouse security) if you feel you need it. You can sometimes get clerks to drag their feet on paperwork to keep a batterer busy while you leave.

Zollman, Stephanie Tabashneck: Listen to upset clients with sympathy.

Choi: Recognize that it is possible that somebody who is upset enough will try to hurt you.

Choi: Try verbal de-escalation first. This means giving the other person a way to get out of the situation or save face without hurting you. There are scripts in use in some professions that deal with vexatious patients, customers or clients.

Choi: Never watch your phone in a situation you believe is high-risk. Look for escape routes on the street, like businesses open to the public.

Choi: It’s best to avoid getting physical, but if you want to be able to defend yourself, get serious about training. It’s hard to remember complex things under stress.

Tabashneck: One red flag is if someone makes a specific threat that includes a time and a place. Ready access to a gun is also a concern.

Huelgo: With domestic abuse, escalating violence and stalking are both signs of danger. The time right after the abused partner leaves is also, statistically speaking, the most dangerous.

Ian Harris: Secure your computer systems and social media accounts, and talk to your domestic abuse clients about what kind of social media their abusers use.

Huelgo: Think about opportunities to make your office more secure.

Choi: If you carry a gun, it’s most effective when the person you feel is a threat knows you have it. This means it’s more effective in states with widespread concealed carry, and for people who can communicate clearly that they have the gun without escalating the situation.

Allen Bailey: Keep a gun it in a desk drawer, because carrying it could escalate a situation.

Lawyers aren’t the only targets of violent clients. Judges must face the possibility of attacks as well.

Nathan Hall, security consultant for the National Center for State Courts, says the state courts have a wide variety of approaches to security, including a few (generally smaller) with not much security at all. Federal courts, because they are all one system and security is handed over to the U.S. Marshals Service, do better.

All state courts should all have a security plan, with responsible parties on a standing security committee. Courthouse personnel should be trained, and the NCSC does offer training. You don’t need bucketloads of money for some of this.

State courts should have security cameras, keep their shrubbery trimmed and maybe offer call boxes at times when cellphones aren’t available.

Judges should have secure parking, and escorts should be available for judges and parties at risk.