Court watch movement is growing in numbers and public attention

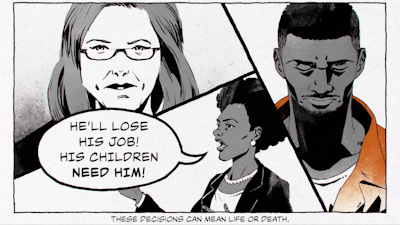

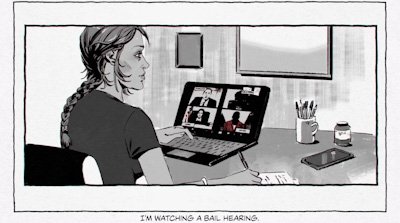

As part of a launch of the National Courtwatch Network in February, the animated short film "The Court Watchers" was released. (Stills from the film provided by Zealous.)

Four squares pop up on a computer screen. A prosecutor, a public defender and a judge occupy three of them. In the fourth, a man wearing an orange jumpsuit appears.

Singer-songwriter Fiona Apple, who narrates the opening scenes of this animated short film, tells us we are watching a virtual bail hearing.

A still from the animated film The Court Watchers shows Fiona Apple at her computer.

A still from the animated film The Court Watchers shows Fiona Apple at her computer.

“Within two days of someone’s arrest, they are brought before a judge like this one, who will decide whether they will be released or incarcerated in jail while their case proceeds,” says Apple, who also provides the film’s score. “These decisions can mean life or death, and they are made within minutes with little information.

“All over the country, thousands of people go through these hearings each day as if in a national assembly line of injustice. But in a growing number of places, people are beginning to hold actors accountable by showing up in court and documenting what they see.”

Related resource: ABA Court Watching provides information on the association’s court watch efforts and training materials for people interested in becoming court watchers.

Apple is one of these volunteers, known as court watchers. For the past two years, she has volunteered with Courtwatch PG, the largest court watch program in the country, to observe legal proceedings in Prince George’s County, Maryland, from her home in Los Angeles.

Apple also has joined a group of advocates calling attention to the concept of court watching and aiming to get more people involved. As part of their launch of the National Courtwatch Network in February, they released the short film The Court Watchers—which is additionally narrated by actor Jesse Williams and Courtwatch PG director Carmen Johnson.

Carmen Johnson is the director of Courtwatch PG, the largest court watch program in the country.

Carmen Johnson is the director of Courtwatch PG, the largest court watch program in the country.

The goal of the network is to bring together individual court watch programs, such as Courtwatch PG, Court Watch Los Angeles and Court Watch NOLA in New Orleans, so they can collaborate and share resources. It also provides information on how people can start their own court watch programs or get involved with existing programs.

“[Protecting] the Sixth Amendment right to a public trial is one of, if not the most, direct, powerful actions that everyday people can take if they are interested in justice, accountability, transparency and the proper functioning of the court system,” says Scott Hechinger, founder and executive director of the advocacy organization Zealous, who helped launch the network.

“But we know this important constitutional right isn’t being fully realized for a range of reasons, and we know court watching is not really at the top of people’s list of racial and social justice imperatives. So how could we make that issue and this intervention engaging and accessible? That’s how this evolved.”

Roots of the movement

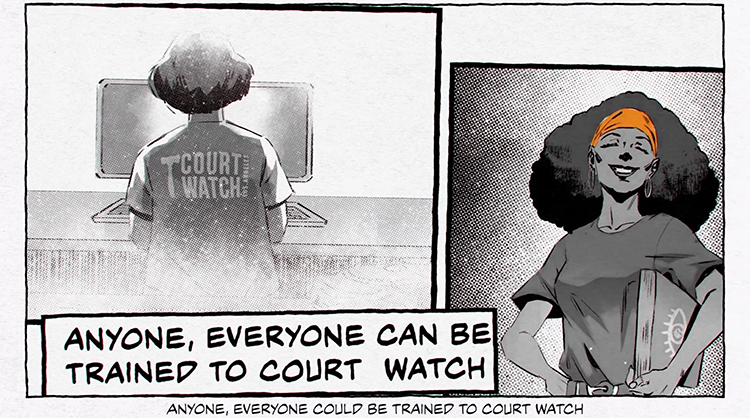

“Court Watch is unique because these are not lawyers,” says Scott Hechinger, founder and executive director of the advocacy organization Zealous. “They are high school students, they are retired librarians and everything in between who are trained in the language of that particular court.”

“Court Watch is unique because these are not lawyers,” says Scott Hechinger, founder and executive director of the advocacy organization Zealous. “They are high school students, they are retired librarians and everything in between who are trained in the language of that particular court.”Hechinger, who worked as a public defender in Brooklyn, New York, for nearly a decade, remembers the first time he saw someone wearing a Court Watch NYC T-shirt in the courtroom. Before that, he says, he rarely saw anyone other than attorneys and court staff attend proceedings.

“If family, friends, citizens wanted to come to court, the door was wide open,” Hechinger says. “You just have to go through a metal detector, and you can go to any courtroom and observe. But no one was there.

“And the reason no one was there is because it’s tough to get to court. It’s tough to take time off from work. And even if you get to court, there is legalese. Folks are talking in penal codes.”

What Hechinger learned about the concept of court watching amazed him, he says. A coalition of volunteers, most of whom have no prior legal experience, are trained to sit in on bail hearings and other court proceedings and document what happens in each case. They share their notes in reports, on social media and in letters meant to hold attorneys, judges, police and jail staff accountable for any problems.

“Court Watch is unique because these are not lawyers,” Hechinger says. “They are high school students, they are retired librarians and everything in between who are trained in the language of that particular court.”

In September 2019, Hechinger started Zealous, a national advocacy and education initiative that helps public defenders, community leaders and people with lived experience challenge injustice through media, storytelling and the arts. Several months later, at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, he received a call from Claire Glenn, then a public defender in Prince George’s County, who was trying to get her clients released from pretrial detention before they contracted the virus.

Several of Glenn’s clients did get COVID-19, and once they could communicate with her, they told her about “horrific” conditions at the jail, she says.

“I found out my clients had been locked in isolation cells for days,” says Glenn, who now works as a staff attorney with the Climate Defense Project. “They were not provided fresh clothing or a bar of soap or a toothbrush for days. They were in the clothing they had been vomiting in and having fever sweats in. And they were denied access to counsel. They wouldn’t even let them use the phone to call their attorneys, let alone their loved ones.”

By this time, Johnson—who was then Courtwatch PG’s sole court watcher—started showing up at bail hearings. Hechinger brought together a group that included Glenn and Johnson as well as attorneys from Civil Rights Corps—who in April 2020 filed a class action lawsuit against the Prince George’s County Department of Corrections—to brainstorm what else they could do to bring awareness to the situation.

They decided to launch a campaign called “Gasping for Justice” to amplify dozens of sworn statements that were collected from prisoners inside the Prince George’s County Jail. Apple and Williams as well as other singers, actors, academics, advocates and public defenders, read those statements in filmed segments that were shared on social media. Hechinger says the campaign went viral and millions of people heard these previously unknown stories. (The civil rights lawsuit later settled.)

“The call to action among sharing it was to sign up for court watch virtually in Prince George’s County,” Hechinger says. “Within four days, Carmen, this lone court watcher, was joined by over 200 volunteers.”

Calling for accountability

Johnson brings lived experience to her work with Courtwatch PG.

In 2015, she was sentenced to nearly five years in prison for conspiracy, wire fraud and making a false statement on a loan application, which arose from two residential mortgage fraud schemes. Johnson, who was then housing chair for the NAACP Maryland State Conference, still says she was not involved in those schemes. She maintains she was targeted and wrongfully convicted after speaking out about illegal foreclosures in Black and brown communities at the start of the foreclosure crisis.

Johnson served three years, and in December 2019, she was approached by Qiana Johnson, the executive director of Life After Release, an advocacy organization led by formerly incarcerated women. Qiana Johnson had founded Courtwatch PG and asked her to come on board.

Since then, Carmen Johnson has observed more than 5,600 bail hearings and other court proceedings, including waiver hearings for juveniles, in Prince George’s County. She also has trained more than 400 volunteers and 100 law students to court watch.

A still from the movie The Court Watchers depicts Carmen Johnson’s first time as a court watcher.

A still from the movie The Court Watchers depicts Carmen Johnson’s first time as a court watcher.

“I don’t want what happened to me to happen to anyone else,” says Johnson, who is also a paralegal and an ABA member. “I had no idea this ‘injustice’ system works the way it works, and we get a lot of people who for the first couple of months are just shocked at the things they are hearing that are happening in the courtroom.”

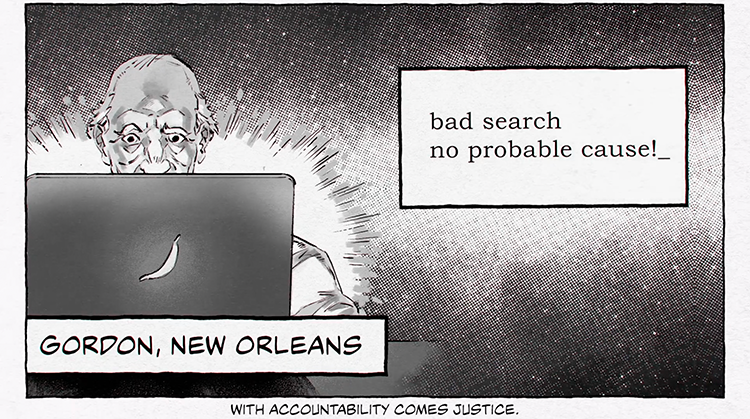

Johnson says one of court watchers’ primary purposes is to ensure court officials are following Maryland Rule 4-216.1, which promotes affordable bonds, including release on personal recognizance and unsecured bonds. Court watchers also report constitutional violations.

Courtwatch PG posts the accountability letters it sends to court and county officials on its website.

In a recent letter, Courtwatch PG asked a judge to correct an error in the record that kept a defendant from being released. According to the organization, a commissioner set a $2,500 secured bond that the defendant could not afford. The judge granted a request to set the bond at 10% since the full amount was unaffordable, but the court’s written records did not reflect the ruling.

Courtwatch PG sent another letter to the police chief raising concerns about police procedures its court watchers encountered in bail hearings. In one case, a defendant was searched by police after a confidential informant claimed a few days earlier that he possessed an illegal firearm. “Stopping and frisking people without sufficient cause violates their constitutional rights,” the letter says.

A third letter involves a woman who Johnson describes as “double victimized.” Courtwatch PG notified several county officials that she was held for public intoxication, but asked repeatedly for a rape exam once she was lucid. Police and jail staff ignored her request. “We feel that this young woman was failed by the police who arrested her, the commissioner’s decision to hold her without bond, the jail’s lack of attention to her request and its medical system, and her judge’s comments in her bond hearing,” Courtwatch PG says.

Courtwatch PG often follows its letters with calls to public defenders and defense attorneys to track what happens in cases. Johnson says she has talked with judges, who told her they not only read the organization’s letters but also act on many of them. Because some courts have limited remote hearings in recent months, she is also advocating for Maryland House of Delegates and Senate bills that would require each court in the state to provide remote audio-visual access to all public proceedings.

For Johnson, being involved in The Court Watchers film and campaign is another way to tell her story and explain why she feels court watching is vital. She is joined in the film by other court watchers who also share what they have seen and heard.

“Injustice happens in empty courtrooms,” Johnson says in the film, which has been viewed more than 200,000 times. “Honestly, I knew I had to be a court watcher because words that are spoken are only in the air. Words that are recorded remain for all to see.”

The Court Watchers from Zealous on Vimeo.

Write a letter to the editor, share a story tip or update, or report an error.