Supreme Court will decide whether family can sue over mistaken raid by FBI SWAT team

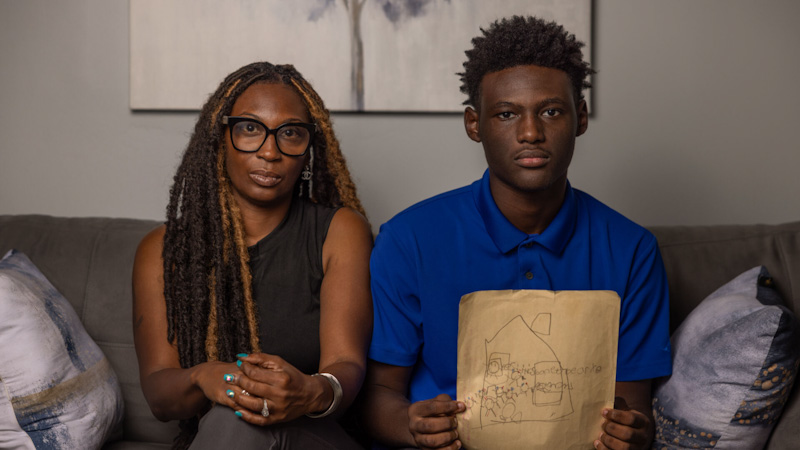

The Institute for Justice represents Curtrina Martin; her son (represented by Martin); and Martin’s partner, Hilliard Toi Cliatt, in a case about whether the U.S. Constitution prevents them from suing the FBI for its mistaken 2017 SWAT team raid of their Atlanta home. (Photo from the Institute for Justice’s Jan. 27 press release)

The U.S. Supreme Court on Monday agreed to decide whether the U.S. Constitution prevents a family from suing the FBI for its mistaken 2017 SWAT team raid of their Atlanta home.

At issue is whether the lawsuit is barred by the Constitution’s supremacy clause and by a liability exception to the Federal Tort Claims Act for federal employees’ discretionary acts undertaken to advance federal policy.

“If the Federal Tort Claims Act provides a cause of action for anything, it’s a wrong-house raid like the one the FBI conducted here,” the cert petition filed by the Institute for Justice, a nonprofit public interest law firm, argues.

The Institute for Justice represents the plaintiffs, Curtrina Martin; her son (represented by Martin); and Martin’s partner, Hilliard Toi Cliatt.

The family members were awakened before dawn one morning in October 2017 by a flashbang grenade exploding in their living room. Martin’s 7-year-old son was separated from his mother while officers stormed the bedroom with guns drawn, according to the institute’s Jan. 27 press release.

Cliatt pushed Curtrina Martin into the closet and was reaching for his shotgun when an FBI agent threw him to the ground. FBI agents soon realized that they had raided the wrong place.

The 11th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals at Atlanta ruled against the family in an unpublished decision in April 2024.

The Federal Tort Claims Act was enacted in 1946 to waive U.S. sovereign immunity and allow damages for certain torts of federal employees when there would be liability under the same circumstances in the state where the acts happened, according to SCOTUSblog and the government’s petition opposing certiorari. Most intentional torts, however, were not allowed.

The law was amended in 1974 to make clear that intentional actions of law enforcement officers could be the basis of suits, according to the Institute for Justice.

“But the FTCA includes a host of exceptions, and circuit courts can’t agree on when they apply,” the press release said.

The 11th Circuit ruled against the family on two grounds. First, the appeals court said intentional-tort claims covered by the law enforcement amendment—for false imprisonment, assault and battery—were nonetheless barred by the supremacy clause because they concern acts with some nexus to furthering federal policy.

No other circuit has taken this position, according to the Institute for Justice.

“The 11th Circuit has created a unique supremacy clause bar to the FTCA that overrides congressional intent,” the cert petition says.

Second, the appeals court barred claims for torts falling outside the law enforcement amendment—for trespass, interference with private property and infliction of emotional distress. The 11th Circuit held that the claims are barred by the discretionary function exception to the Federal Tort Claims Act, which bars claims arising from a government official’s performance of a duty or a function that involves discretion.

The appeals court reasoned that FBI agents had discretion in preparing for execution of a warrant, and their decisions are susceptible to policy analysis.

The courts are “badly split” over the discretionary function exception, the cert petition says.

The case is Martin v. United States. The SCOTUSblog case page is here.

Publications covering the cert grant include SCOTUSblog, Law.com and the Washington Post.

Write a letter to the editor, share a story tip or update, or report an error.