Lawyer-turned-playwright celebrates Broadway debut with powerful legal drama

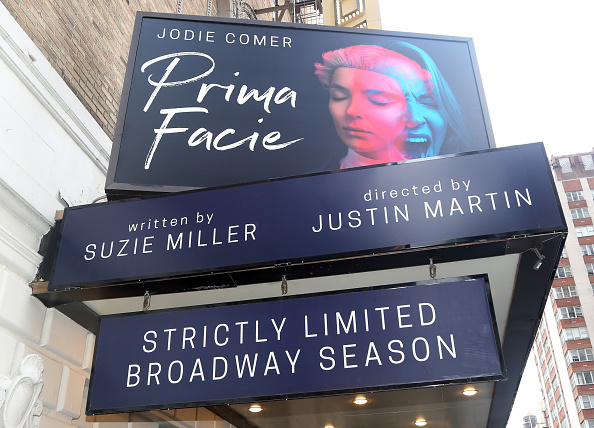

The opening night of the new play "Prima Facie" on Broadway at the John Golden Theatre on April 23 in New York City. Photo by Bruce Glikas/WireImage via Getty Images.

A new play on Broadway is redefining the meaning of authentic dramatic experience. Prima Facie is a one-woman play centered on an ambitious lawyer who, after building her reputation representing men accused of rape, must navigate the same legal system to seek justice for herself after her sexual assault. What adds resonance to this drama, however, is its author—a former criminal lawyer who worked with sexual assault survivors.

Suzie Miller worked with crime victims, children and marginalized communities in her native Australia before transitioning full time to playwriting. Critical acclaim followed, and she earned a spate of international awards for her work. Today, Miller writes for the stage, the screen and most recently the page—her first novel drops later this year. Prima Facie was first staged in London’s West End, where it earned myriad awards and rave reviews. Now, the play has a 10-week run at the John Golden Theatre on Broadway.

Q. How does it feel to have a play opening on Broadway?

A. Fantastic! I am such a lover of New York and everything about New York. I have actually had another play on in New York years ago, and it went really well. Fast-forward almost 15 years, and now I am back but on Broadway, and it’s a whole different gig. Even in the rehearsal room, you know that the walls are infused with the voices of great actors, and you feel like you’re part of theater history, which is such a lovely feeling.

Q. How much of Prima Facie is pulled from your personal experience?

A. When I was at law school, I was really struck by the sexual assault cases we’d read and by the transcripts and the kinds of questions asked of the women. It’s such a difficult area for women to be vocal about because there is so much unwarranted shame attached to it, there are so many rape myths that go to the heart of what the community thinks, and the law is a reflection of the community. This is a really serious crime against a person—the body of the woman is the scene of a crime. I looked at consent law, and it comes from generations and generations of a male perspective. You wonder whether the courts of law have actually thought about what the crime of sexual assault is and the weight of it on the victim. There are laws of affirmative consent, but it still is a he-said-she-said.

Suzie Miller worked with crime victims, children and marginalized communities in her native Australia before transitioning full time to playwriting.

Suzie Miller worked with crime victims, children and marginalized communities in her native Australia before transitioning full time to playwriting.

Q. And the justice system can be even more harrowing for women of color.

A. This play speaks to class and gender because those are my lived experiences. But I did work as a criminal and human rights lawyer in Australia, and I took many statements of sexual assault from women every week, and I can tell you, when you add race to the mix, there’s a whole new level of discrimination and lack of belief—especially when the perpetrator is a white man. Those issues coalesce, and you start to realize the weight of disbelief that women have to carry. I worked at the Aboriginal Legal Service for a long time, back in the days when there were very, very few indigenous lawyers—there are more now—and remember thinking at the time, it was like going back in the ages in terms of how the police treated indigenous people, the courts treated them, and in terms of the way women were utterly disbelieved.

Q. What inspired you to go into public-interest law instead of going the law firm route?

A. I did a year of my law degree at the University of Toronto through a law school exchange, but I wanted to finish my degree in Australia, so I did go back. Having said that, when I was in Canada, I met … lawyers who particularly changed my life and, looking back, impacted my move to theater. One of them was Catharine MacKinnon. She gave a lecture about feminism and law, and that was mind-blowing for me as an Australian law student in my early 20s. When you look at the law through the lens of feminism, there is so much wrong, and there is so much that needs to be fixed. I got to the end of my law degree and realized I was going to be a criminal lawyer, [but] I also realized I didn’t want to do rape cases. So I decided to become a solicitor trial advocate, where I could actually refuse to take some cases if I wanted to. I did no sexual assault work at all, but I did take sexual assault statements from victims, and I would take those to court in civil matters and try to get compensation from the government.

Q. How did you get into playwriting? You are a lawyer, and your undergraduate degree is in science. Where in there did you realize you had a talent for creative writing?

A. I did my honors degree in immunology, and I was going to do a PhD in immunology, and I also majored in mathematics, which I loved. But then I decided I wanted to do something more vocational—that had a job at the end of it. And I was a real talker, as you can tell, so I thought, “I have to do something where I can speak and read and really be engaged with words.” So I did a law degree, but while I was working on the law degree, I did a masters in theater and film because I’ve always loved them. When I did my theater and film degree, I thought, “I really want to write.” I then went to the National Institute of Dramatic Art in Sydney—they have seven people they train a year in playwriting—and after that, there was no looking back.

Q. In 2010, you moved to London to pursue playwriting, and now you divide your time between London and Sydney. That sounds very glamorous! Is it?

A. It’s not glamorous, let me tell you. My husband is a judge in Australia, but he comes to London, I go there; and our two children, who are now adults, go in between. You give up a lot for your career, but so do all women. All of us have pumped milk in some random place somewhere. All of us who have traveled for work know it’s an act of trust—you have to trust that your partner is able to step up to the plate, to actually be a parent, not a babysitter, and that everything will be OK in your absence. I started writing plays after I had my first child, and when I first started leaving to do work in theater in London, people would rush over with meals for my husband. I’d say, “Don’t do that! They’re his children; he knows what to do!” And they’d say, “But he works full time!” And I’d say, “So do I!”

Q. And now you’ve added a third continent to the mix!

A. Yes, and my husband and children are arriving soon. Everyone here has been so amazing. The great thing about Americans is this sense of can-do and optimism. Even when things are tough, they’re like, “We’re going to work even harder to make things better!”

Playbills at the opening night of the new play “Prima Facie” on Broadway at the John Golden Theatre on April 23 in New York City. Photo by Bruce Glikas/WireImage via Getty Images.

Playbills at the opening night of the new play “Prima Facie” on Broadway at the John Golden Theatre on April 23 in New York City. Photo by Bruce Glikas/WireImage via Getty Images.

Q. You’ve written a lot of plays. You even had a play staged here in New York in 2008, Reasonable Doubt, for which you won the New York Fringe Overall Excellence Award for Outstanding Playwriting. But did you think that Prima Facie would be the one to go the distance, to have a sold-out run in the West End and come here to Broadway?

A. When I wrote it, I didn’t think it was. I always had my eye on New York and Broadway specifically, but I hadn’t actually formulated which play would be “the one.” I wrote this play in a burst of passion. I wasn’t thinking about taking it on the road or that it would even be sent anywhere, to be honest. In many regards, it’s this beautiful gift of a play. But the other thing is so many people have written to me after they’ve seen it. Like, thousands and thousands of people—DMs, emails through my agent, even hand-written letters left at stage door—to share their experiences. They have said things that were so moving, like, “I’ve never, ever told anyone, and after I saw the play, I went home and told my mum.” The relief and their sense of being supported was astonishing. Other women said, “I always wanted to go to the police but didn’t, but after I saw the play, I thought, I at least want to make a statement so his name was on a statement somewhere, so if it happened to someone else, it would be appropriate that he would be called up.” Just this solidarity of sisterhood that came about, I was really astonished that a play could do that. The play was also seen by judges from the Old Bailey in London. One of the judges called me and said, “I am the judge who writes the directions to the jury, and after I saw the play, I redrafted it and sent it to all the judges.”

Q. That’s amazing. And an impact you probably couldn’t have achieved as a lawyer.

A. The irony was that I went to law school because, perhaps naively, I wanted to change the world, and I think with playwriting, I can still change the world. I can create a sense of empathy for a character that people can’t dismiss. They have to think about it, and then the next time they think about it in the real world, that empathy will come to bear. I know that sounds naive too, but it comes from that same place—it’s the same passion I had as a young lawyer when I thought, “I have this a tool that I can use to change the world.” Now, I have both tools—theater and law together.

Q. What advice would you give to a lawyer who’s dreaming of writing and perhaps wants to do that full time instead of practicing law?

A. People think I left my job as a lawyer because I didn’t like it. But I loved my job as a lawyer. I loved going to court; I loved fighting in court. I just loved theater that much more. It was so much more of a personal expression to be able to get a pen and play with words. But until I actually left the law, I worked like an absolute dog on weekends writing. People who are lawyers don’t realize that their capacity for working long hours is really high, their ability to focus is really high, and the quality of what they write is already higher than that of a person who just decides to write because they’ve already been trained to write. I think what makes you a writer is writing. That’s all it is. It’s not a mystery to tell a story. Anyone who has ever litigated and stood up in a courtroom or put together submissions for court is a born storyteller.

The play has since been nominated for four Tony Awards.

Updated May 8 at 1:48 p.m. to add information about the play’s four Tony Awards nominations.

Write a letter to the editor, share a story tip or update, or report an error.