Biden reverses course on Trump’s immigration policies—but will high-skilled workers return?

In 2019, Chinese citizen Leo Wang's application for an H-1B visa was denied, and he had to leave California. “I still believe in the American dream,” he told the AP. “It’s just that I personally have to pursue it somewhere else." AP Photo/Ben Margot.

One of President Joe Biden’s signature campaign promises was to undo former President Donald Trump’s immigration policies. Since taking office, Biden has wasted no time, getting rid of several of his predecessor’s proclamations and orders with a similar stroke of the pen. On his first day in office, he overturned previous executive orders and presidential proclamations affecting people from Muslim and African countries.

At the beginning of June 2021, Biden formally ended the Migrant Protection Protocols—more commonly known as the Remain in Mexico program—that required asylum-seekers to remain in Mexico until their case is decided in U.S. immigration court.

On the other hand, under Title 42 of the U.S. code, another provision from the previous administration that allows customs officers to prohibit entry of any individual who may pose a communicable disease danger (like COVID-19) to the U.S. is still in effect. According to the American Immigration Council, in February, 72% of migrants at the border were expelled under Title 42. (The Biden administration exempts unaccompanied children from the order.)

President Joe Biden signs an executive order on immigration on Feb. 2. AP Photo/Evan Vucci.

President Joe Biden signs an executive order on immigration on Feb. 2. AP Photo/Evan Vucci.Nevertheless, Biden has made clear that he wishes to make it easier for immigrants to live and work in the U.S.—and he’s connecting this to America’s ability to succeed.

For instance, whereas Trump’s Proclamation 10052 stated that “admission of workers within several nonimmigrant visa categories … poses a risk of displacing and disadvantaging United States workers” during the economic recovery following the COVID-19 outbreak, Biden has criticized it for harming the country by preventing family reunification and harming “industries in the United States that utilize talent from around the world.”

As Donald Jay Wolfson, immigration practice partner at Kauff McGuire & Margolis in New York City points out, the Biden administration’s goal is “re-injecting humanitarianism into the way we approach immigration” through ending the Muslim travel ban, reinstituting and strengthening the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, or DACA, expanding employment visas and increasing refugee admissions.

Most importantly, the administration is backing the U.S. Citizenship Act of 2021, which is designed to provide pathways to citizenship and strengthen labor protections for them, as perhaps the most important signal sent by the Biden administration.

“It will provide a path forward for the millions of undocumented workers now living in the United States,” Wolfson explains. “It is estimated that more than 650,000 immigrants, both family and employment-based, were affected by Trump bans, and these immigrants will now be able to join their families and their employers in this country.” The act has been introduced in both the U.S. Senate and House of Representatives and has been referred to their relevant committees.

Supporters of immigration reform gather before marching in favor of a path to citizenship and an end to detentions and deportations on April 28 in Washington, D.C. AP Photo/Jacquelyn Martin.

Turning the pipeline back on

Most news stories focus on the influx of people coming to America to seek shelter and protection. But U.S. immigration policies were designed to also attract highly talented individuals, according to Morristown, New Jersey-based Alka Bahal, partner at Fox Rothschild and co-chair of the firm’s Immigration Practice Group.

“That talent is needed to drive innovation, business and the overall success of our economy,” she says. “The fact that some of the world’s best and brightest will now think twice about choosing to emigrate to America—or not—is a significant problem for us, in the long run.”

U.S. companies have always benefited from immigrants and those with nonimmigrant visas. A 2017 study by the National Bureau of Economic research, “Immigration and the Rise of American Ingenuity,” reveals that between 1880 and 1940, foreign-born expertise played an outsized role in U.S. inventions, accounting for 19.6% of all inventors—and by 2017, immigrants made up 30% of inventors.

And according to a 2020 report by the U.S. Census Bureau, 47% of the foreign-born population that arrived in the U.S. in the past decade had a bachelor’s degree or higher, compared to just 36.3% of native-born Americans.

Many of those degrees are in high-demand occupations in STEM, or science, technology, engineering, mathematics, areas. For example, a report by the Council of Graduate Schools reveals that international students made up 17.8% of total graduate school enrollment in the fall of 2019. However, they made up 49.8% of students in engineering, 49.0% of students in mathematics and computer sciences, and 33.9% of students in physical and earth sciences.

“For the last several years certain key industries that rely on nonimmigrant workers have been hit hard,” says immigration lawyer Michael J. Freestone, partner at Tully Rinckey in Washington, D.C., and vice-chair of the ABA Section of International Law’s Committee on Immigration. “IT businesses, financial service firms, and multinationals who rely on the L1 visa saw significant upticks in denials and requests for evidence.” (L-1A and L-1B visas authorize intracompany employees in managerial positions or with specialized knowledge to work and live in the U.S.)

And Freestone believes that perhaps the most damaging actions targeted F-1s and J-1s and their paths to H-1Bs and ultimately green cards. (An F-1 visa is for students admitted to a full-time program of study at a U.S. college or university who can show proof of funding from any source. With a J-1 visa, students must receive 51% of their financial support through a scholarship, fellowship or other direct support from an institutional or government sponsor. A H-1B is for an individual who obtained a degree in a specialty occupation and wants to stay in the U.S. to work in that area.

“These actions will have lasting consequences as an entire generation of foreign students potentially may not remain in the U.S. for post-graduate work,” Freestone says.

Karan Murgai, an IT management consultant for a multinational based in Dallas, works on his laptop in his house in New Delhi on June 30, 2020. Murgai, who returned to India to attend his father’s funeral, was stranded in India after an executive order signed by former President Donald Trump suspended applications for H-1B and other high-skilled work visas from abroad. AP Photo/Manish Swarup.

Karan Murgai, an IT management consultant for a multinational based in Dallas, works on his laptop in his house in New Delhi on June 30, 2020. Murgai, who returned to India to attend his father’s funeral, was stranded in India after an executive order signed by former President Donald Trump suspended applications for H-1B and other high-skilled work visas from abroad. AP Photo/Manish Swarup.

What has already been lost?

While Biden can reverse policies with the stroke of a pen, the administration can’t wave a magic wand and undo the damage of the past four years. According to the State Department’s 2020 Report of the Visa Office, from fiscal years 2016 through 2020, immigrant visas issued at Foreign Service Posts declined from 617,752 to 240,526. Nonimmigrant visas declined from 10,381,491 to 4,013,210.

Among specific immigrant categories, visas for immediate relatives fell from 315,352 to 108,292. Employment-based preference visas declined from 25,056 to 14,694.

“Certainly, Trump’s negative view of immigration has tainted the nation’s immigration system in numerous ways—far beyond the clearly visible executive orders or written policy changes, but also insidiously weaving an anti-immigration sentiment throughout the Federal immigration system and among certain populations of Americans,” Bahal says. “The effect is subtle, but certain, resulting in an uptick of more scrutiny, harsher analysis, and more denials than ever before.”

Immigration attorney Michael G. Murray in Austin, Texas, points to Trump-era policies put in place by Stephen Miller and Jeff Sessions for much of the damage.

“A good example is the strict rejection policy for many USCIS applications for any missing information or unchecked box.” Murray says this policy not only discouraged filers, but it also caused some asylum-seekers to miss the one-year deadline to file their application. “Rates of denials and requests for evidence in the employment-based context have increased to the point that many U.S. employers have already shifted to hiring American to avoid the disruptions.”

In fact, Murray says the restrictive policies of the last administration led him to shift his practice to handle more family-based and deportation cases.

“Before America can attract the best and brightest to join our workforce, Biden’s signature ceremonies need to work their way down to the practices and policies of immigration officials formerly conditioned to keep the sign ‘closed,’” he says. “It will come down to a lot of retraining.”

His view is shared by Elizabeth Ricci, an immigration lawyer at Rambana & Ricci in Tallahassee, Florida.

“What has already been lost is time and talent, as many applicants were wrongly denied green cards.” Some left voluntarily while others were forced to leave without a pending or approved application. “The result is that those highly skilled workers will now have to wait additional time abroad without being able to immediately contribute to our economy or talent pool—and many will stay abroad or emigrate to countries such as Canada, Germany or Australia.”

However, Clete Samson, a partner with Kutak Rock and a former attorney for the U.S. Department of Homeland Security, points out that the country’s immigration problems didn’t start with the last president.

“Unfortunately, the nonimmigrant worker population has become accustomed to being victims of the shifting tides of American immigration policies,” he explains. “For at least the last 25 years, delays, stays, injunctions and targeted executive actions have always impacted the non-immigrant worker population in the United States, as well as the immigration benefits and opportunities that were available to them.”

The lack of consistency certainly plays a role in the uncertainty workers feel. “In general, all presidents have used executive orders to impact immigration policy, but the whiplash effect of the most recent changes to our immigration policies will likely create some deterrent to highly skilled workers who fear being caught in limbo as to their long-term immigration status,” Samson says.

Will highly skilled workers come back?

Will Biden’s reversals and immigration friendly efforts be successful in luring the most talented workers back to the United States? Bahal doesn’t think so. Beyond the last administration’s negative messaging, she also believes the last four years have changed the world’s view of America.

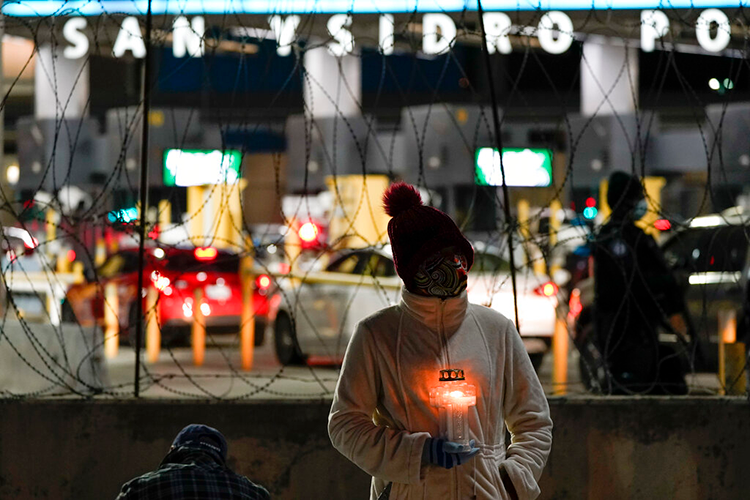

A woman holds a candle during a vigil the night before Joe Biden’s Jan. 20 inauguration at the entrance to the San Ysidro Port of Entry along the border between the United States and Mexico. AP Photo/Gregory Bull.

“Combined with the steep learning curve experienced the world over regarding new ways to work effectively but remotely, this creates new circumstances such that highly educated and highly skilled foreign nationals may no longer need to actually come to the U.S. to achieve the ‘American Dream,’” she explains.

In addition, Bahal believes that foreign nationals who are in the U.S. on a visa will always be wondering if the next president, or the one after that, will share Trump’s view on immigration.

“Given that it can take decades for a foreign national to become a citizen of the U.S., foreign nationals will always view the U.S. immigration system as carrying some risk,” she maintains.

Immigration attorney Sumaiya Khalique, the head of Khalique Law in New York City, has a more optimistic tone. She admits that the damage done over the past four years can’t be fixed overnight, but she believes it is possible for the pendulum to swing in the other direction—and stay there.

“Many people who were denied asylum, work visas, family petitions in the last four years, did not get the refuge they sought in the U.S., lost career opportunities and could not be united with their families,” she acknowledges. “But despite all the obstacles faced in the last four years, people still want to immigrate to the U.S.; asylum-seekers want to find safety, students want to study, professionals want to work, family members want to be reunited; and they want to become permanent residents—and eventually U.S. citizens.”

Write a letter to the editor, share a story tip or update, or report an error.