Nearly 20 years ago, Scalia explained why he didn’t consider jet trip a gift

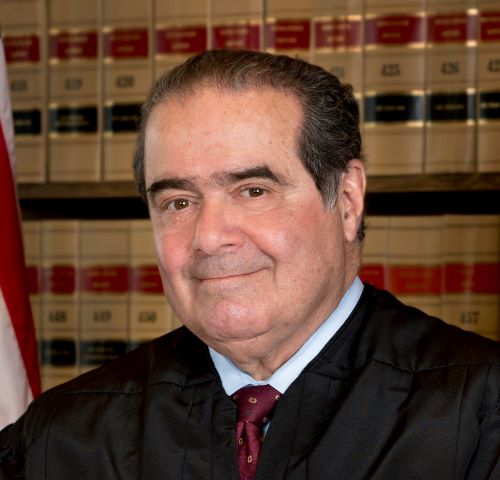

The late U.S. Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia. Photo by Steve Petteway, PD US Courts, via Wikimedia Commons.

Like U.S. Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas, Justice Antonin Scalia became the butt of jokes by late-night comedians for accepting a free jet ride.

In 2004, Scalia traveled for free on a government jet with then-Vice President Dick Cheney to go duck hunting in Louisiana. He then refused to recuse himself in a case involving Cheney’s energy task force, reasoning that Cheney was sued in his official, rather than individual, capacity.

Recent reporting by ProPublica disclosed that Thomas has traveled on billionaire Republican megadonor Harlan Crow’s superyacht, flown on his private jet, and stayed at his private resort in New York and his ranch in Texas.

The New York Times took a look at the memo that Scalia wrote in which he explained why he did not think recusal was necessary.

“Justice Scalia’s discussion of whether the plane ride was a gift, what it was worth and whether it needed to be disclosed helps illuminate the legal standards that apply to Justice Thomas’ travels,” the New York Times reports.

The trip, Scalia said, was not a gift. Scalia reasoned that the trip cost the government nothing because there was space available on the vice president’s jet, which was going to Louisiana with or without him. Cheney was required to fly on government planes because of national security requirements.

“And though our flight down on the vice president’s plane was indeed free,” Scalia wrote, “since we were not returning with him, we purchased (because they were least expensive) round-trip tickets that cost precisely what we would have paid if we had gone both down and back on commercial flights. In other words, none of us saved a cent by flying on the vice president’s plane.”

And there was no need to disclose the trip, Scalia said, under Ethics in Government Act provisions that exclude transportation provided by the United States from the reporting requirement.

A motion for Scalia’s recusal had cited newspaper editorials calling for him to step aside in the case. If he recused, Scalia said, it would “encourage so-called investigative journalists to suggest improprieties and demand recusals for other inappropriate (and increasingly silly) reasons.”

“While the political branches can perhaps survive the constant baseless allegations of impropriety that have become the staple of Washington reportage, this court cannot,” Scalia wrote. “The people must have confidence in the integrity of the justices, and that cannot exist in a system that assumes them to be corruptible by the slightest friendship or favor and in an atmosphere where the press will be eager to find foot faults.”

Scalia died in 2016. He was replaced by Justice Neil Gorsuch.

Write a letter to the editor, share a story tip or update, or report an error.