Tipping the Scales

Once a year, the chief justices of the Southern state supreme courts gather to share experiences, learn from judicial educators, discuss trends that are common in the court systems of the Deep South and seek solutions. Last year, when the elite group of jurists gathered in Nashville, Tenn., they recognized that they themselves are a trend: Eight of the 13 Southern states—Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee and Texas—have female judges leading their courts of last resort—more than any region in the country.

“We all looked at each other and noticed that there were a lot of us,” says Tennessee Supreme Court Chief Justice Janice Holder. “While it wasn’t a coordinated event, it didn’t just happen either.”

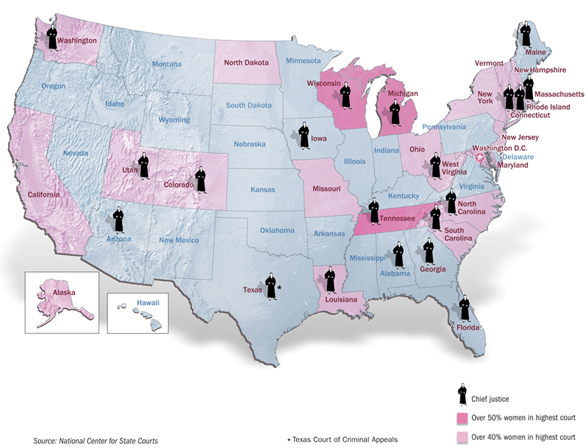

Twenty states across the nation now have a woman serving as chief justice—more than at any time in the history of the United States.

In fact, women compose 26 percent of state judiciaries, compared with 22 percent of the federal judiciary, according to The American Bench: Judges of the Nation, a new report by Forster-Long Inc.

Alabama Chief Justice Sue Bell Cobb

Women now make up 48 percent of law school graduates and 45 percent of law firm associates, according to the report.

Nowhere have the gains in gender diversity been greater than in the South. Four of the states in that region—Florida, Georgia, Kentucky and South Carolina—have as high or higher percentages of women on their state courts as do California, Connecticut, Illinois, Michigan and New Jersey, all of which are considered much more liberal or progressive in seeking diversity.

But it is in the Southern supreme courts where the gender diversity is most obvious and publicly displayed.

“I ask people if they know how many women chief justices there are, and they answer two or three,” says Alabama Chief Justice Sue Bell Cobb. “When I tell them, they are shocked. But it really blows them away when I tell them how many there are of us in the South.”

Former Georgia Chief Justice Leah Ward Sears, who retired last summer, had the same experience.

“The South often gets a bad rap for race and gender,” says Sears, who was her state’s first female chief justice and second African-American justice. “But I would go to New York and tell people that I was chief justice, and they would be floored.”

Nine of the 13 state supreme courts in the South have multiple women as justices, as does the District of Columbia. Five states have three or more—the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals, which is that state’s court of last resort on criminal matters, has four female judges. Tennessee is one of three states with a majority of women on its supreme court. Michigan and Wisconsin are the other two. Two states have no women as justices, and neither—Idaho and Indiana—is in the South.

Before 1990, there had only been eight female chief justices in the nation’s history. The first was Arizona Chief Justice Lorna Lockwood, a great-niece of Abraham Lincoln, who was chosen by her peers on the Arizona Supreme Court in 1965.

Florida Chief Justice Peggy Quince

PUSHING FOR PROGRESS

Florida Chief Justice Peggy A. Quince says the growing numbers of women serving as chief justice in their states is something that comes out of many reforms, but especially several originating within the legal profession in the last few decades.

“By 1990, a Florida Supreme Court commission on gender bias had released its final report cataloging in withering detail the ways that discrimination against women was both tacitly and explicitly enforced in the legal profession,” she says. “This report directly led to a number of changes in rules of court, statutes and common practices that sped the rate of reform.”

The Florida commission, for example, found that the state’s judicial nominating commissions generally applied different standards to male and female judicial candidates, such as giving greater weight to traditionally “male” areas of practice and being unduly concerned with the child care arrangements of female candidates. The result, the commission found, was that women were not appointed to judgeships in numbers proportionate to their membership in the bar.

As a result of the gender bias report, the Florida JNCs changed their rules to require that each candidate be given the option to identify their own race, ethnicity and gender. All the completed addendums also are forwarded to the governor, whether or not the applicant is nominated.

The Florida Code of Judicial Conduct also now prohibits judges from being members of any organization that practices invidious discrimination. Many other state supreme courts created similar gender bias task forces during this time period to examine how women were treated in the court system. As a result, more women were appointed or elected to the bench; and, over time, a well-established network of female mentors and role models emerged in the profession.

“The fact that so many women now serve or have recently served as chief justice in their states is the result of these decades of work,” Quince says. “They have reached levels of seniority and built professional networks that have placed them in these roles as leaders.”

Georgia Supreme Court Chief Justice Carol Hunstein

Georgia Supreme Court Chief Justice Carol Hunstein, who chaired Georgia’s gender bias task force, agrees, but also points out that each of the eight Southern chief justices took different routes to get where they are.

The chief justices in Florida and Tennessee were appointed by the governor, ran in retention elections, and then were elected chief by their colleagues. In Louisiana, the chief justice was elected by a district in the state and then promoted to chief due to seniority on the supreme court. The Alabama chief justice and Texas Court of Criminal Appeals presiding judge were chosen directly by the citizens in statewide partisan elections. North Carolina’s chief justice was initially elected to the state supreme court and was then appointed chief justice by the governor. The South Carolina legislature appoints its chief justice.

While supreme court justices in Georgia run statewide in nonpartisan elections, the tradition has been for the justices to retire during the middle of their term, allowing the governor to fill the spot with an appointment. The Georgia justices then internally select one of themselves to be chief, usually based on seniority.

“The women chiefs tend to have gotten to the position differently from men,” says Holder, who couldn’t even get a job as a lawyer out of law school. “Women came up through the system the hard way. You have to develop skills to survive and to get to the next level.”

THE POLITICS OF CHANGE

But the common denominator for the eight Southern chief justices is politics. At a time when bar associations and advocates of judicial independence decry judicial elections as improperly influencing the rule of law, it is those exact politics that are credited for the success of these eight female chief justices.

For example, then-Gov. Zell Miller of Georgia called it “good politics” when he appointed Justices Hunstein and Sears in the early 1990s. And Chief Justice Jean Hoefer Toal had served 13 years in the South Carolina legislature when that body selected her to serve on the state’s highest court in 1988 and then promoted her to chief in 2000.

“We’ve hit the 21st century and women are the majority—the majority of college students, the majority of law students, the majority of new lawyers and, most importantly, the majority of voters,” says Celinda Lake, who is a political adviser and pollster for Cobb, Hunstein and Sears.

“The voters recognize qualities in judicial candidates that the legal and political elites don’t,” Lake says. “The elites disqualify a candidate for not going to the right law school or being editor of law review. The people want judges who are good listeners and thoughtful, and women are very strong with voters in those characteristics.”

Lake says that women who are judicial candidates have to overcome one common public bias to win at the ballot box over dads and college-educated men.

“The hardest bias to overcome is toughness, which is laughable if you know any of these chief justices personally,” says Lake.

In each of Lake’s three successful Southern state supreme court elections, she focused on the stories of the three women.

She points to the 2006 re-election campaign of Justice Hunstein, who was challenged by a former Bush administration lawyer who was backed by pro-business interests. Lake pushed Hunstein’s life story of overcoming polio, handling two bouts of bone cancer, having a leg partially amputated, being a single mother of three whose husband died leaving her in near poverty, and working her way through college and law school.

Hunstein’s campaign also displayed her toughness, running television advertisements pointing out that her opponent’s mother had sued him for taking her money, and that his sister had accused him of threatening to kill her. And she strongly countered attacks that she was soft on crime by showing statistics that she sided with the prosecution as often or more often than her fellow justices.

The result: Justice Hunstein won re-election with 63 percent of the vote and won all 159 counties in Georgia.

“The voters in Georgia, given the opportunity to elect in an open seat, have, in the last two elections, chosen women candidates for the court of appeals,” says Chief Justice Hunstein.

LIVING TESTIMONY

The five Southern chief justices who agreed to be interviewed for this article concur that diversity on the bench is as important today as ever before.

“In a real sense, a judge’s life experience can serve as a lens to magnify what others cannot see,” says Chief Justice Quince.

“I think of the case decided last year by the U.S. Supreme Court involving a 13-year-old girl forced to undergo a strip search based on scant evidence of misconduct. Some of the questions at argument suggested that the male justices saw this procedure as little different than changing for gym class.

“But Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg commented that her male colleagues had never been 13-year-old girls and simply did not understand the degree of humiliation involved. And the court’s majority agreed that the search was unconstitutional. To me, that ex ample illustrates why a diversity of life experience is crucial for a bench that reflects our larger society and its concerns.”

DIVERSITY ON THE BENCH

Diversity in the Legal Profession: The Next Steps, a report released in March by the ABA’s Presidential Diversity Commission, says lack of diversity “can malign the legitimacy of not only lawyers, but the law itself.” Among the commission’s recommendations, it urges that judges and state bar associations lobby their states to make judicial appointments more transparent. It suggests that state and local governments modify selection and screening criteria to aid the recruitment of more women and minorities to the bench.

Today, at least 25 states have more women on the state bench than the federal bench in their state, and 31 percent of all sitting state supreme court justices are women.

Write a letter to the editor, share a story tip or update, or report an error.