Stories You Won't Read in Books

Photo by Barbara Proud

Among Washington, D.C.’s grand buildings, the Law Library of Congress might seem an afterthought.

The structure is functional, early 1980s architecture. It sits just across the street from the main Library of Congress, one of the Federal City’s most gloriously appointed edifices.

But behind its bland façade sits the world’s largest law library, with 2.6 million volumes. And the stories of the people who use them and how the library acquired many of those books are every bit as interesting as what’s contained between the covers of the collection.

The library, which celebrates its terquasquicentennial this month, was created in 1832. Of its 2,011 original volumes, 639 had been part of Thomas Jefferson’s private library. In its early years, new books were selected by the chief justice of the United States.

In the 1920s and 1930s, the Soviet government found itself in need of hard currency. So it confiscated historical documents that were in private hands and sold them to governments and private dealers in the West. That’s how much of the czar’s library ended up in Washington.

Congress relies so much on the library that it is open whenever either house is in session—even in the middle of the night.

When the current Afghan government came to power, it could not reinstate pre-Taliban laws because the Taliban government had destroyed all the statute books. English translations in the Law Library helped replace some of them.

And lawyers across the country call on the Law Library for help finding obscure citations from the laws of more than 260 nations and dependencies in its collection. Bloomington, Minn., immigration lawyer Richard Breitman, who has gotten assistance with foreign family law matters, says, “They often come up with stuff so unfindable and valuable it looks like a diamond.”

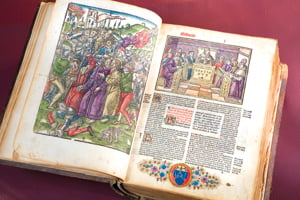

The Law Library has an extensive rare book collection. It has several copies of Decretum Gratiani, a compilation of canon law written in the 12th century and used as a legal textbook. With distinctive woodcut illustrations, this copy (photo above) was published in Venice in 1514.

Sidebar

Terry Carter is a senior writer for the ABA Journal.