Meet the groups helping to get women elected

Photo illustration by Sara Wadford/Shutterstock

Rebecca Dallet took her first seat on the bench during a mock trial in her high school government class. She spent the morning next to the judge, watching him and the impact he had on people who appeared before him.

She thought she might also want to be a judge, and that idea stayed with her through nearly 11 years as an assistant district attorney in Milwaukee County in Wisconsin.

In 2007, after she was appointed the county’s first female presiding court commissioner and realized she was doing a lot of things judges do, she knew it was time.

What Dallet didn’t know was how to run—let alone win—a successful election campaign.

Rebecca Dallet: “It’s very important that as women, we have leadership roles in the law. … If we’re not participating, if we’re not in leadership roles, our voices aren’t being heard, and our experiences aren’t being taken into consideration.” Photo by Wayne Slezak/ABA Journal.

“I think a lot of women need encouragement, and they need more role models, which we don’t have as many of,” she says. “I think that is true with women leadership in the law, period.

“If you don’t see yourself—and this goes for minorities, too—in that role … it’s hard to see yourself being there.”

The year 2020 is the centennial of the 19th Amendment. A hundred years after getting the vote, what do women’s legal rights and representation look like? The ABA Journal’s yearlong series examines these issues.

Additional Resources

• 19th Amendment Centennial of Women’s Right to Vote

• ABA Commission on the 19th Amendment

Dallet discovered the White House Project, a nonpartisan nonprofit organization founded in New York City in the late 1990s to increase women’s leadership in business and government. During a Vote Run Lead training programs in Milwaukee, Dallet not only learned the basics of campaigning—such as how to raise money and write an elevator speech—but gained a new sense of emowerment.

Female leaders spoke to Dallet, the mother of three daughters, and other participants about how to balance campaigning and their families, and how to overcome the persistent public perception that women aren’t suited for leadership. She called on her new connections for guidance as she ran for and won a seat on the Milwaukee County Circuit Court in 2008.

“It provided the training, the networking, the encouragement, some of the nitty-gritty stuff, but really just a place to get started,” Dallet says of the White House Project.

She was reelected in 2014, then decided to run for the Wisconsin Supreme Court in 2018. She had handled nearly 12,000 cases and more than 250 jury trials and wanted to make a larger contribution to the practice of law.

Dallet won and is now one of five women who serve on the seven-justice court.

“It’s very important that as women, we have leadership roles in the law,” she says. “Because of the impact all of these decisions have on all of us if we’re not participating, if we’re not in leadership roles, our voices aren’t being heard, and our experiences aren’t being taken into consideration.”

Taking the lead

Erin Vilardi helped the White House Project start the Vote Run Lead initiative after graduating from college in 2003. A gender and sexuality studies and politics double major at New York University, Vilardi read Ms. Magazine at an even younger age and believed the world would be a better place if women were in power.

After the White House Project shuttered in 2013, Vilardi launched Vote Run Lead the following year as a stand-alone organization in New York City that trains women around the country to run for office. Its in-person and online curriculum, “Run As You Are,” hinges on the idea that women without political backgrounds still have the life experience, talent and capacity to lead.

Erin Vilardi, CEO Of Vote Run Lead, works at a 2019 national training in New York City. Photo by Aisha Ude Photo.

Vilardi, CEO of Vote Run Lead, points to two reasons why it’s important for more women to create laws and make decisions at each level of government. The first is the “role model effect,” meaning that seeing women in office inspires more women and girls to run in the future. The second, she contends, is that women approach lawmaking differently.

“We put things on the agenda that have never been legislated before, often related to women and families,” Vilardi says. “We have a different perspective when it comes to the economy and jobs and equal pay. Women often tend to—and this still holds true even though we are in a hyperpartisan state right now—work across the aisle and do the business of government a little more transparently and inclusively.”

Vote Run Lead is one of dozens of organizations that are empowering women who want to run for office.

The Women’s Campaign School at Yale University opened nearly 26 years ago and has since attracted thousands of participants, including U.S. Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand of New York and former U.S. Rep. Gabrielle Giffords of Arizona.

Higher Heights for America serves as the “political home” for black women, while other organizations, such as Republican Women for Progress and the progressive Democratic group Run for Something, build up women in their own parties.

The ABA, also recognizing the importance of women’s full and equal exercise of their right to vote and participate in government, selected “Your Vote, Your Voice, Our Democracy: The 19th Amendment at 100” for this year’s Law Day theme.

ABA President Judy Perry Martinez contends the legal profession and the public need to understand that including more women at the table and in leadership benefits everyone.

“If you take it from the point of the 19th Amendment, and what was done and fought for in order to get that amendment, to me, there is no way but forward,” Martinez says. “And going forward means making sure that women have full participation—it’s not only some women in Congress, but there is a critical mass of women in Congress—and that we understand the notions of equality and parity in the greatest sense.”

By the numbers

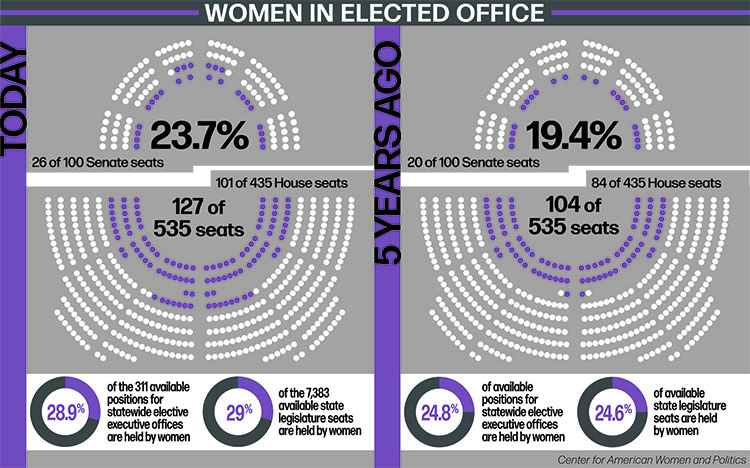

Women are gaining ground in public office in part due to historic 2018 midterm elections that resulted in record numbers serving in the U.S. Congress and state legislatures across the country.

Women now hold 127, or 23.7%, of the 535 seats in Congress, according to the Center for American Women and Politics at the Eagleton Institute of Politics at Rutgers University. This breaks down further to 26 of the 100 seats in the Senate and 101 of the 435 seats in the House of Representatives.

In 2020, women also hold 28.9% of the 311 available positions for statewide elective executive offices, which include governor, lieutenant governor and attorney general, and 29% of the 7,383 state legislature seats.

Infographic by Sara Wadford/Shutterstock

Just five years ago, women held only 104, or 19.4%, of the seats in Congress. Twenty of those seats were in the Senate, and 84 were in the House. Women also held only 24.8% of available statewide elective executive office positions and 24.6% of state legislature seats.

Debbie Walsh, the director of the Center for American Women and Politics, explains that not many women were running for office in 2015 or in previous years, but that rapidly changed with the election of President Donald Trump.

“When 2016 came along, it seemed to inspire more women to be politically engaged,” she says. “I think a lot of women were rather stunned by the outcome of the election.”

Women’s representation on the country’s courts of last resort—the courts of final appeal in a jurisdiction—has also increased in the past 10 years. According to data provided by the National Center for State Courts, 34.8% of seats on these courts were held by women in 2019, versus 31.1% in 2009.

The ABA Profile of the Legal Profession also shows that women made gains in the federal judiciary in recent years, growing to 27% in 2019 from 19.3% in 2009.

Walsh expects to see significant numbers of women running in the 2020 election, but she says it’s too early to tell if they will set records. In addition to watching new candidates, she’ll be paying particular attention to how women who were elected in 2018 fare in their reelection bids.

In Vote Run Lead’s efforts to bolster the female base, it has trained more than 30,000 women on how to run for office, work on a campaign or get out the vote. The organization has a network of more than 125 trainers in about 30 states, and in May 2019, it held its largest day of training for nearly 3,000 women online and in 20 cities.

“It is not for us about some moment of resistance,” Vilardi says. “This is really about a movement and ascension of women in power at every level, putting more women into those positions of power.”

Historical perspective

For many, the movement began with the “Year of the Woman” in 1992.

After slow progress for women through the 1980s, a combination of influential factors—including Clarence Thomas’ 1991 confirmation to the U.S. Supreme Court despite his former Department of Education and Equal Employment Opportunity Commission subordinate Anita Hill’s allegations of sexual harassment—resulted in a significant number of women running for office and winning elections.

Front row, from left: Missouri Democratic U.S. Senate candidate Geri Rothman-Serot; former U.S. Rep. Geraldine Ferraro, D-N.Y.; Sen. Barbara Mikulski, D-Md.; and Illinois Democratic U.S. Senate candidate Carol Moseley Braun celebrate women’s victories on June 8, 1992. Photo by Laura Patterson/CQ Roll Call via Getty Images.

Twenty-nine women filed for Senate seats and 11 won their primaries, while 222 women filed for House seats and 106 won their primaries in 1992, according to data from the Center for American Women and Politics. Prior to the election, four women were serving in the Senate and 28 women were serving in the House. By the start of the 103rd Congress in 1993, those numbers had increased to seven in the Senate and 47 in the House.

Patricia Russo, who had served as an intern for U.S. Rep. Bella Abzug—a Democrat and lawyer from New York City known for her work in women’s rights—was on the ground in Connecticut helping several women-organized campaign fundraisers.

“We were feeling heartened that year, and a small group said, ‘Wow, we cracked that glass ceiling and leveled the playing field. All American women are going to see these phenomenal women who just ran and won, they’re going to step up and say, Why not me?’” Russo says.

But that didn’t happen.

In response, Andree Aelion Brooks, a contributing columnist and news writer who covered the women’s movement for the New York Times, met with Russo and a few others to discuss her vision for a campaign school for women.

They knew they wanted it to be an intensive program and to mimic the energy of a political campaign. They wanted it to be nonpartisan and issue-neutral. And they wanted to offer it to approximately 80 women at a time at Yale University.

With the support of U.S. Rep. Rosa DeLauro, a Democrat who still represents the district that includes Yale in New Haven, Connecticut, and then-U.S. Rep. Nancy Johnson, a Republican who represented another district in the state, the Women’s Campaign School at Yale hosted its first class in 1994.

Women interested in running for office or running a political campaign attend the Campaign School at Yale University’s 2019 five-day summer session. Photo by Mara Lavitt.

In the beginning, says Russo, who is now the organization’s executive director, most participants were white and in their mid-40s. Many of them had legal backgrounds and were passionate about politics but waited to get involved until after their children were older.

Due to what Russo calls the “Barack Obama phenomenon,” most participants who enroll in the school now are women of color. Their median age is late-20s, they have diverse career experiences and as many as 10% are from other countries.

“It adds a richness and texture to our program,” Russo says. “When women come together to work collaboratively, they will see irrespective of where they live or their political affiliation that we have more in common than not.”

Stacey Chavis held several jobs in politics, one as the finance director for Democratic U.S. Rep. Hank Johnson of Georgia, before attending the Women’s Campaign School in 2007. She gravitated toward its session on campaign fundraising and still references information she learned there about donations and compliance as the founder of Campaigns Academy, a campaign training company in Atlanta. The Women’s Campaign School also inspired Chavis to attend the University of Georgia Law School, from which she graduated with a master’s degree in the study of law in 2019. She says understanding election law gives her another advantage when it comes to training candidates.

Chavis plans to stay behind the scenes for now and encourages other women to consider that route. Not everyone wants to be a public official, she says, and more female campaign managers, finance directors, communications directors and data analysts are needed. “Also, [so are] advocates and activists, because once we get folks into elected office, we need to help them stay accountable and vote for good legislation, ordinances and laws.”

The Campaign School, as it’s now known, created a new level of training that in one day covers the basics of running for office or managing a campaign. Since 2017, it has hosted nearly a dozen of these programs for more than 2,000 women who had never been politically active.

“We see all of these women surging and continuing to surge and really understanding in a very holistic, comprehensive way all that it takes to prepare yourself for success,” Russo says.

Building a diverse coalition

Despite a swell in the number of women of color running for office and winning, they continue to be severely underrepresented in seats of power.

Higher Heights for America is one organization working to change that by increasing black women’s participation at federal and state levels and as mayors in the 100 largest U.S. cities.

It was founded in 2011 after Glynda Carr and Kimberly Peeler-Allen, who worked together previously on Kevin Parker’s election campaign for the New York state senate, were discussing how many times in their careers they had found themselves in rooms that weren’t diverse.

Higher Heights for America sees significant opportunities to empower black women who want to run for office. Photo courtesy of Higher Heights for America.

“We were literally able to wave to the couple of other people of color in the room,” says Carr, now president and CEO of Higher Heights for America and sister organization Higher Heights Leadership Fund. She helped launch the #BlackWomenLead: Political Leadership Training Webinar Series, which touches on various topics, including communications and developing an action plan. The goal is to reach women who are sitting in their living rooms, cooking in their kitchens or even listening while they’re driving.

Its efforts are helping move the needle, particularly in the House, where 80 black women ran for seats and a record 41 secured nominations in 2018, according to a report on the status of black women in politics released by the Higher Heights Leadership Fund and Center for American Women and Politics. Today 22 black women, the most ever, are now serving in the House.

The winners included the first black congresswomen from Connecticut (Jahana Hayes), Massachusetts (Ayanna Pressley) and Minnesota (Ilhan Omar, who is also one of the first Muslim women elected to Congress).

Those successes, however, are not seen across the board. In the Senate, there were no black female nominees in 2018 and haven’t been in four of the past seven congressional election cycles, according to the report. Fewer than 2% of all statewide elected executive officials are black women, and only seven of the mayors in the nation’s 100 most populous cities are black women. In addition, no black woman has ever been elected governor of a state.

“There are three top barriers for black women,” Carr says. “One is navigating the political system; [another] is access to early funding, so fundraising; and the other one is the question around electability. Electability ties to your ability to raise money.”

She says Higher Heights sees significant opportunities to empower black women who want to run for office, including in districts that have not historically voted for candidates of color.

“Our work is to build a network of black women and our allies to help recruit, train and support these black women and try to help shape the narrative about the changing face of leadership,” Carr explains.

Growing parties

There have also been recent efforts to increase the network of Republican women interested in politics.

The Campaign School joined forces with Republican Women for Progress in March 2019 for its first basics training for nearly 65 Republican women. Jennifer Pierotti Lim, a co-founder of the grassroots policy organization, says the partnership is a major initiative because the Republican party hasn’t historically invested in women.

As a result of the 2018 midterm elections, the number of Republican women declined in the House, among governors and other statewide elected executive officials, and in state legislatures, according to data from the Center for American Women and Politics.

The Republican Women for Progress executive team from left: Alanna Fridfertig, outreach director; Kodiak Hill-Davis, co-founder and political director; Ariel Hill-Davis, co-founder and policy director; Jennifer Pierotti Lim, co-founder and executive director; and Meghan Milloy, co-founder and executive director. Photo by Own Your Wonder.

“So much of what we do is just that entry pep talk,” Lim says. “You’re good enough to run for office. We’ll support you.

“We are starting to develop that culture of Republican women helping Republican women, teaching Republican women that all of these trainings are open to them as well.”

Republican Women for Progress was first known as Republican Women for Hillary, an organization created by Lim in reaction to Trump being named the Republican presidential nominee in 2016.

After the election, Lim, an attorney and former director of health policy at the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, saw a need to inspire more Republican women to get involved in politics. She helped launch the existing organization in 2017, and it has since opened chapters in 12 states.

Lim sees many attorneys run for office because they feel empowered to discuss laws and policies, and how they can be improved. One of those attorneys is Rosemary Becchi, a Republican who is running for Congress in New Jersey’s 11th District.

The mother of three daughters began her career with the Internal Revenue Service and now works as a strategic advisor and counsel in the Washington, D.C., office of Brownstein Hyatt Farber Schreck. She agrees that her legal experience makes her a stronger candidate, particularly as she analyzes issues and thinks about campaign positions.

“This is the first time I’ve run, but I find myself drawing on my experience as I decide how to approach problems and how to move forward,” Becchi says. “It’s been incredible training for it.”

She relies on Republican Women for Progress to connect her to resources that help her fundraise and establish name recognition. The organization also came to her aid in October after it was reported that a state party leader had emailed Republicans and told them not to donate to her campaign.

“You really need organizations and people like them in this process because they absolutely know how to handle the situation,” Becchi says. “Particularly on the Republican side, if we are ever going to change the mentality about women and electing women, it begins with organizations like theirs that aren’t afraid to stand up and push back.”

Other organizations, including Run for Something, are helping women on the other side of the aisle face their own challenges as newcomers in local elections.

Run for Something engages progressive men and women under the age of 40 who want to run for school boards, city councils and state legislatures. In the past, says Amanda Litman, its co-founder and executive director, there weren’t many places people running in those races could find support.

“There are a lot of resources for people who want to run for Congress, and there are certainly resources for people who can raise money,” Litman says. “But there aren’t resources for you if you are brand new to this and don’t even know where to start.

“There is no guarantee that the state party will even answer your email,” she adds.

Litman and the organization’s other co-founder, Ross Morales Rocketto, launched Run for Something on Trump’s inauguration day in 2017. They expected to hear from about 100 people in the first year and planned to work with them on weekends. Instead, they heard from 1,000 people who wanted to run for local office in the first week; as of today, that number has grown to more than 46,000.

Amanda Litman: “There are a lot of resources for people who want to run for Congress … but there aren’t resources for you if you are brand new to this and don’t even know where to start.” Photo by Noam Galai/Getty Images for Global Citizen.

Run for Something provides direct support to candidates, and of the nearly 300 people it has helped elect in 49 states and Washington, D.C., 54% are women. Litman says they talk often about how to reach more women, knowing that those who hold local positions will gain the experience needed to serve in higher offices later.

“We want to make sure that activists, donors, people in the media are paying attention to local races, not just because local policy is what actually affects people’s lives, but because these are the people who will eventually become members of Congress and presidents one day,” she explains.

Run for Something endorsed Aurora Martinez Jones as she campaigned for a seat on the Travis County District Court in Texas for the first time in 2017. She had been appointed an associate judge to preside over child welfare cases two years earlier but thought she could have a greater impact in an elected position as a district judge.

She didn’t ask anyone’s permission to run, which meant she also didn’t have much political support.

“That endorsement was the first real acknowledgment I felt like I had, definitely from a national organization, but [also] from an organization that gave my campaign legitimacy,” Jones says. “When I got this endorsement, it made people say, ‘Oh wow, we should take this woman seriously.’”

Jones lost that election but is now running unopposed for another seat on the court. She hopes to show her community that her experiences as a child of immigrants from Jamaica and Mexico, a woman of color and the mother of two daughters make her a stronger leader.

“The way in which the world has perceived me and my ability to empathize with people like me do play into the way I make decisions from the bench,” Jones says. “It’s important that we have representation from all different backgrounds so that we are reflecting the people who are coming into our courts and making decisions with enough empathy to understand where they are coming from and with enough competency to understand different cultures.”

See also:

Law Day 2020: Your Vote, Your Voice, Our Democracy

This article was originally published in the April/May 2020 issue under the headline, “It’s Her Term.”

Write a letter to the editor, share a story tip or update, or report an error.