Lawyers and cognitive decline: Diminished capacity may bring ethics problems for sufferers

The most common ethical problem for a lawyer experiencing cognitive decline is violation of the first rule of ethics – the duty of competency. Photo by Lightspring/Shutterstock.com

It could be a wildly inappropriate comment, a sudden loss of memory, a pattern of nonresponsiveness, a startling lack of professional judgment, or a gross mistake that an attorney would never make.

Any, or all, of these could be a telltale sign that an attorney is suffering from cognitive decline or even dementia. And cognitive decline in practicing lawyers can raise a host of ethical issues and sometimes lead to lawyers taking disability status.

Cognitive decline can result from a variety of medical or health problems. Perhaps the lawyer had a stroke, changed medication or had auditory loss—or it could be the onset of dementia. Before colleagues and partners determine the proper course of action, or whether intervention is appropriate, the root cause should be identified.

“It is important for colleagues to act when they see a fellow lawyer showing signs of cognitive decline,” says Terry Harrell, executive director of the Indiana Judges and Lawyers Assistance Program. “The good news is that oftentimes there can be a number of things that cause such a decline that can be remedied.”

age is a factor

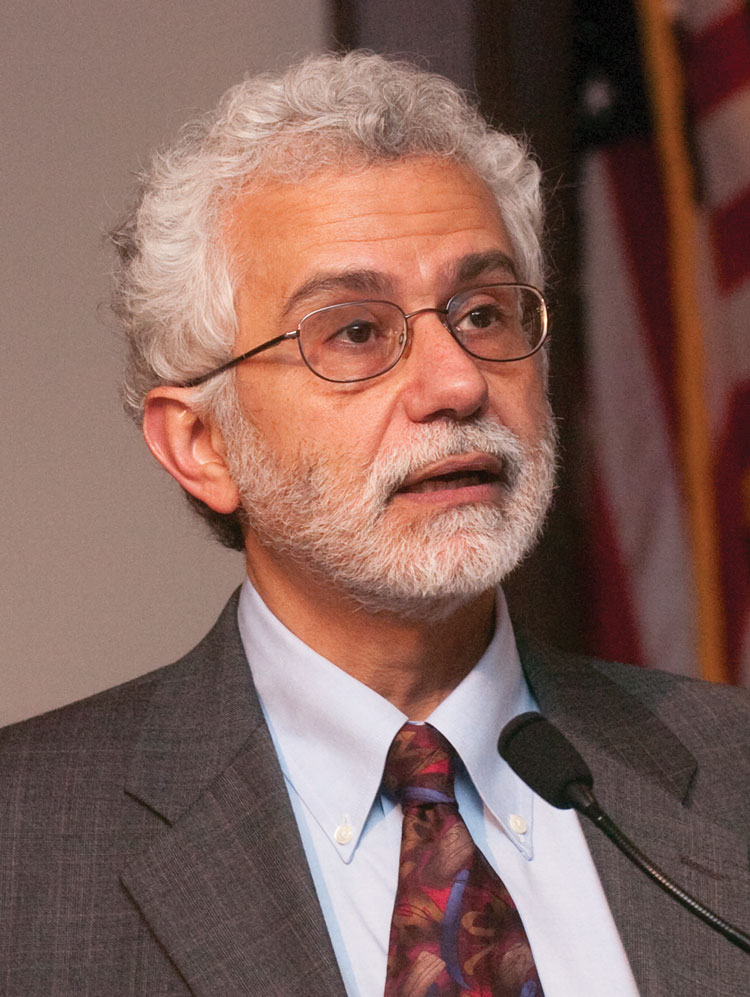

Peter Joy: “Lawyers suffering cognitive decline is a growing problem, just as dementia in the general population is increasingly an issue.” Photo courtesy of Washington University School of Law.

She relates the story of a judge who contacted her organization expressing concern about an attorney in the judge’s courtroom. The attorney was not responding to the judge’s questions. One of Harrell’s co-workers asked the judge whether the attorney showed the same level of nonresponsiveness outside the courtroom. The judge said no. It turned out the attorney was simply suffering from hearing loss.

Harrell gives another example of an attorney, a great speaker, who suddenly started slurring words in court. Some colleagues thought he might have had a stroke. However, upon questioning, they learned the problem was caused by a recent change in his medication. These problems can surface in people of all ages, but they most commonly occur with senior lawyers.

The ABA’s Commission on Lawyer Assistance Programs wrote in its 2014 Working Paper on Cognitive Impairment and Cognitive Decline that “the most common cognitive disorders of aging, however, are neurodegenerative diseases that involve progressive deterioration of the brain over time.”

The paper notes that the risk of dementia increases dramatically over time. “The age at onset is typically after 65, and the likelihood of developing Alzheimer’s doubles every five years after the age of 65. After age 85, the risk reaches nearly 50 percent.”

“Lawyers suffering cognitive decline is a growing problem, just as dementia in the general population is increasingly an issue,” says ethics expert Peter A. Joy, a professor at the Washington University School of Law in St. Louis.

“People are living longer, and the older one is, the higher the odds are that one will get dementia. This is especially an issue for lawyers in private practice as sole practitioners or small office settings who are practicing law as they advance in age. Many midsize-to-larger firms’ partnership agreements set 65 to 70 as a mandatory retirement age, in part either to avoid or to decrease the odds of having to face this issue,” he adds.

The most common ethical problem of a lawyer with cognitive impairment is violating the first rule of ethics—the duty of competency. In the ABA Model Rules of Professional Conduct, Rule 1.1 says: “A lawyer shall provide competent representation to a client. Competent representation requires the legal knowledge, skill, thoroughness and preparation reasonably necessary for the representation.”

Lawyers with cognitive deficiencies might not be able to recognize the strengths and weaknesses of cases, advance the proper arguments, or even understand the arguments advanced by opposing counsel.

A related rule is 1.3: “A lawyer shall act with reasonable diligence and promptness in representing a client.” Cognitive issues can cause lawyers to run afoul of this rule. “A frequent ethical problem for lawyers suffering from cognitive decline is a lack of diligence,” Harrell says. “They miss deadlines and calendar dates and statutes of limitations.”

Joy says lawyers in solo or small firms often feel the impact more because there aren’t others in the office to pick up the slack.

“For lawyers who are sole practitioners or in office-sharing arrangements, they often have no one else to help them recognize the issues they are facing,” he says. “For those lawyers, they often miss filing deadlines, and sometimes they miss court hearings, both of which trigger issues of competency under Rule 1.1 and diligence under Rule 1.3.”

Duty of Other Lawyers

Terry Harrell: “The good news is that oftentimes there can be a number of things that cause such a decline that can be remedied.” Photo courtesy of Indiana Judges and Lawyers Assistance Program.

Theresa Gronkiewicz, senior counsel for the ABA’s Center for Professional Responsibility and staff counsel for the Commission on Lawyer Assistance Programs, says, “State lawyer assistance programs are extremely vital in helping to deal with lawyers who may be suffering from cognitive decline.”

This is particularly true because ethical issues can arise for lawyers witnessing the effect of cognitive impairment on a colleague. Under certain circumstances, this can trigger a lawyer’s obligations under Rule 8.3(a), which provides that attorneys must report the ethical misconduct of their peers.

“If a lawyer in the firm knows that the impaired lawyer committed a violation of the Rules of Professional Conduct that raises a substantial question as to the impaired lawyer’s fitness, pursuant to Rule 8.3(a), a report must be made to the disciplinary authorities,” Gronkiewicz says.

In Formal Opinion 03-431, “the ABA Standing Committee on Ethics and Professional Responsibility explained that if a lawyer suffers from a condition materially impairing the ability to practice, failure to withdraw ‘ordinarily would raise a substantial question requiring reporting under Rule 8.3,’ ” Gronkiewicz says.

Experts say lawyer assistance programs can be a vital cog in helping attorneys who are having cognitive and competency issues. Such programs can also assist in determining the proper course of action, which usually involves a one-on-one conversation with the lawyer as a first step.