How can aging judges know when it's time to hang up the robe?

Illustration by Sara Wadford/ABA Journal; Shutterstock

Phyllis Hamilton suffers from back pain and carries a lumbar cushion everywhere. She makes sure that no matter where she sits, she’s ready with the right kind of ergonomics.

“If you have a physical problem, you are going to take care of it so you can continue to do your job,” the Oakland-based chief judge of the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California says. “You are going to get the assistance that you need.”

Judges have a responsibility to the public to function to the best of their ability. To Hamilton, that means not only protecting their physical well-being but also their cognitive health, which the National Institute on Aging defines as being able to think, learn and remember clearly.

Northern District of California Chief Judge Phyllis Hamilton always brings a lumbar cushion with her to the courthouse. Photo by Tony Avelar/ABA Journal.

Hamilton, 68, has been on the bench for 20 years as a district judge and was a magistrate judge for nine years before that. Since becoming chair of the Ninth Circuit Wellness Committee in 2010, she has taken the lead in promoting healthy aging and recommending that judges consider voluntary cognitive examinations to review their brain function.

“If I started feeling that I had cognitive issues, I would want to know about them,” Hamilton says. “I would want to see what the problem is and if I could delay it.”

She adds that many judges from the San Francisco-based 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals are forward-thinking in this area, as shown by their willingness to participate in the University of California San Francisco Memory and Aging Center’s longitudinal study on the effects of aging on older adults’ cognition.

From July 2018 to June 2019, the Ninth Circuit Wellness Committee helped recruit 36 judges who completed several hours of neuropsychological tests assessing their attention, memory, orientation and other skills. Participants included circuit judges; active and senior district judges; active magistrate and bankruptcy judges; and several retired judges. Their average age was around 67, but a few were in their 50s, and the oldest was 87.

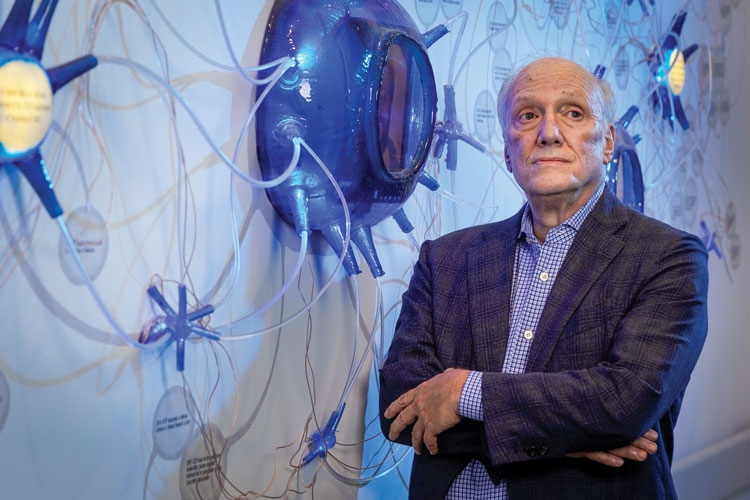

Dr. Bruce Miller, the director of the UCSF Memory and Aging Center, oversees the study. His team has evaluated more than 1,000 people, and he says by including the cohort of federal judges, they will gain insight into strengths that emerge as they age, as well as how they compare to engineers, doctors and other professionals.

Bruce Miller: “I don’t know of something quite like this, where we are looking at a particular occupation so comprehensively.” Photo by Tony Avelar/ABA Journal.

“I shouldn’t say this has never been done before, but I don’t know of something quite like this, where we are looking at a particular occupation so comprehensively,” he says.

The 9th Circuit’s novel efforts come during a national conversation about aging Americans, who are continuing to live and work longer. According to the Administration for Community Living’s latest report, the population of people in this country who are 65 and older increased from 38.8 million in 2008 to 52.4 million in 2018. It estimates that total will reach 94.7 million in 2060.

The federal judiciary has not been immune to the upward trajectory: The the average age of active and senior judges now approaches 69. According to additional data provided by the Federal Judicial Center, about 66% of all judges will be 65 or older by the end of 2020. Its data also shows 33% will be 75 or older by the end of the year, while just over 11% will be 85 or older.

Reactions to this trend are mixed. Lawyers, law professors and even members of the judiciary voice concerns that judges are serving too much time on the bench without ensuring their cognitive skills stay sharp. They have called for mandatory retirement and cognitive testing as well as a more consistent approach to addressing cognitive decline.

But members of the legal community who have experience with neuroscience argue that the question of when a judge should step down is complex. In attempting to reframe the conversation, they say studies such as the one led by Miller show that judges shouldn’t face doubts over their cognition once they reach a certain age. Rather, they want to focus more attention on normal aging and the support that can be provided to judges as they grow older.

Miller plans to recruit at least 75 judges before they publish the study. He confirms that initial results show their cohort tests high on executive function, which includes the ability to organize, plan and handle multiple tasks simultaneously.

Hamilton, who participated alongside her colleagues, adds that the judges’ test scores will establish their baseline in the study, because many have agreed to be reevaluated every one to two years.

The scores can also be shared with the judges’ personal physicians.

“We go into our annual examinations, and our hearts are checked, our cardiovascular systems are checked, the doctor checks our lungs—but nobody really checks our brain,” Hamilton says. “So we’re trying to raise awareness of the ability to have some impact on your overall brain health.”

Setting the scene

The debate over federal judges and their lengthy tenures often involves the U.S. Constitution.

According to Article III, U.S. Supreme Court justices and federal circuit and district judges “shall hold their offices during good behavior” with no cutoff for age. They could be removed from office, but only through impeachment by the House of Representatives and conviction by the Senate.

Federal judges also have the option of taking senior status once they meet certain age and service requirements. That happens when a judge turns 65 and has served at least 15 years on the bench or reaches any other combination of age and years of service that equals 80.

Judge Richard Posner, who served on the Chicago-based 7th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals for 36 years, wrote in his book Divergent Paths that “not being subject to compulsory retirement and able to delegate much of their work to staff, federal judges sometimes fail to retire even when old age and its related ills have greatly impaired their judicial performance.”

Before Posner retired at 78, he called for a mandatory retirement age of 80 for federal judges.

President Donald Trump’s administration has prioritized putting young conservative judges on the federal bench, in part because they serve lifetime appointments and can shape the nation’s laws for many years. According to the American Constitution Society, the Republican-controlled Senate had confirmed 220 Article III judges under this administration by early November.

Among the judges confirmed were Supreme Court Justices Neil M. Gorsuch, Brett M. Kavanaugh and Amy Coney Barrett. Progressive legal groups, such as the Center for American Progress, argue that the Supreme Court confirmation process has become too political and support term limits for justices.

Justice Stephen G. Breyer, who was nominated by President Bill Clinton and confirmed in 1994, said during an event in 2019 that he wouldn’t oppose an 18-year term limit. He said then it would “make life easier” since he wouldn’t need to worry about when to retire.

Arthur Hellman: “Disability is best handled behind the scenes, typically by the chief judge of the circuit.” Photo by University of Pittsburgh School of Law.

Arthur Hellman, a law professor at the University of Pittsburgh who studies the federal courts, argues that even if there were sound policy arguments for mandatory retirement for federal judges, the issue is a nonstarter. It would require a constitutional amendment, something he doesn’t see support for in today’s political climate.

“I don’t see any possibility of getting the constitutional amendment through the very elaborate process that it requires, even though on this particular issue, there may be a large degree of consensus,” Hellman says.

Matters of state

State courts are another matter, and many states have taken different approaches to judicial retirement. According to the National Center for State Courts, 32 states and the District of Columbia require appellate or general jurisdiction court judges to retire at a specific age. Although 70 is the most common, some set retirement at 72, 74 or 75.

William Raftery, a NCSC senior analyst, says proposals to raise the mandatory judicial retirement age from 70 to 75 succeeded in Pennsylvania and Florida in 2016 and 2018, respectively, but similar efforts in Oregon, Hawaii, Louisiana, New York, Arizona and Ohio all have failed.

“It’s a tricky situation,” Raftery says. “As judges get older, as we have an older population, why can’t someone work until 74 or 76 on the bench, especially if they keep getting reelected? The counterpoint is, the voters simply don’t want to do it.”

In the early 2000s, a joint committee of the ABA’s Judicial Division and Senior Lawyers Division recommended 75 as an appropriate retirement age for judges, says Ruth Kleinfeld, who chaired that committee and retired in 2015 after 24 years as a U.S. administrative law judge.

“We looked at what point one’s age would interfere with the ability to maintain a proper judicial function, and now that I am 80, I see there are a lot of people who are in very good shape at least until 75,” says Kleinfeld, who is also a past chair of the SLD. “At that point, some people can even take senior status, as federal judges do, and still maintain a good working capability.”

It’s often challenging for federal judges with life tenure to determine when exactly to retire.

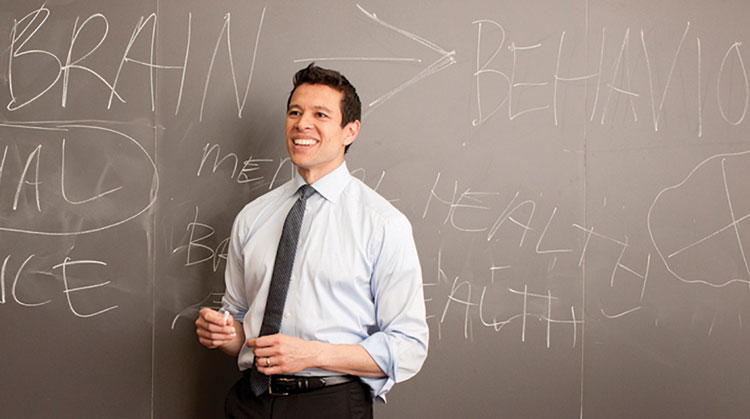

Francis Shen: “Age is not destiny.” Photo by Josh Kohanek.

Francis Shen is a professor at the University of Minnesota Law School and executive director of education and outreach for the MacArthur Foundation Research Network on Law and Neuroscience. In studying law and neuroscience, he observes that individuals experience aging differently.

“Age is not destiny,” he says. “You could be at 80, 82, 85 or older and still have tremendous cognitive faculties. “You combine that with the fact that there are things that come with age, namely wisdom, that you want in a judge, and it becomes difficult to know in any particular case if this is someone who should no longer be on the bench.”

An additional challenge, Shen says, is that symptoms of cognitive decline are not always apparent.

They can include memory loss and impairment and changes in emotional and social control and regulation, but those can be subtle or gradually appear over time.

Illustration by Sara Wadford/ABA Journal.

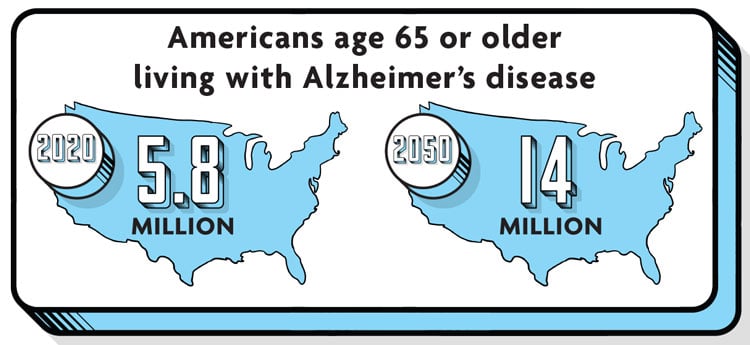

According to the Alzheimer’s Association, about 5.8 million Americans age 65 or older now live with Alzheimer’s disease, the most common form of dementia. This number is projected to increase to nearly 14 million by 2050.

The extent of mild cognitive impairment or dementia in the judiciary remains largely unknown. Hellman says lawyers and court staff are often reluctant to report judges who may be experiencing problems. And if an issue is reported, it is usually handled by a chief judge before an official complaint is filed.

“Disability is best handled behind the scenes, typically by the chief judge of the circuit, although the chief judge of the district can also play a role,” Hellman says.

“The key problem is getting the information to the people who have the responsibility and are in the position to do something about it.”

Robert Tembeckjian, administrator and counsel for the New York State Commission on Judicial Conduct, also finds it difficult to uncover problems at the state level.

“When a judge goes off the bench for medical assistance, the tendency is for that judge’s colleagues to cover for a while and not reveal to the judicial conduct commission that there is a problem,” he says. “And almost invariably, when we become involved, the judge, usually in consultation with his or her family, agrees to retire.”

Tembeckjian refers to a recent case involving Kings County Supreme Court Justice ShawnDya Simpson.

The commission began investigating reports in October 2019 that Simpson’s “demeanor toward litigants, lawyers and others had become erratic and at times intemperate,” and “she was frequently absent from court, arriving very late or leaving very early, or not arriving at all, despite the fact that she was scheduled to preside,” according to an August news release announcing Simpson’s retirement.

In the wake of these incidents, Simpson was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease. She is in her mid-50s.

In the news release, Tembeckjian and Simpson’s attorneys said in a joint statement that they hope “her legacy will be burnished by her fortitude in revealing her condition and the degree to which this action might destigmatize Alzheimer’s disease and inspire others to learn more about how to recognize and cope with it.”

Focus on wellness

Before engaging in what may be the first study of its kind, the 9th Circuit was the first to establish a committee that provides programs and resources related to judicial wellness and disability.

Hamilton, a member since 2008, says it has succeeded in encouraging judges to think about their physical, mental and brain health and take better care of themselves.

“We are ubiquitous,” Hamilton says. “At every conference, there is a wellness table. We always have programs. Even though some people might have heard of us many times in the past, there are always new judges coming on board.”

Judge Phyllis Hamilton: “It’s personal. It’s sensitive. But it’s important for judges to talk about it.” Photo by Tony Avelar/ABA Journal

The committee started in 1999 as the Ninth Circuit Task Force on Judicial Disability. After a formal charter was adopted, the task force recommended several initiatives, including a confidential telephone counseling service that judges could use if they had concerns about themselves or their colleagues.

The Judicial Disability Committee, which later changed its name to the Judicial Wellness Committee and then to the Ninth Circuit Wellness Committee, was created in October 2000 and established the 9th Circuit’s Private Assistance Line Service in 2001.

Richard Carlton has been a consultant to the circuit on cognitive issues since that time. He also staffs the PALS program, which receives about four calls each year from chief judges or other judges who are worried about a colleague who is struggling to process information or issue decisions.

Carlton offers guidance on how callers can handle the situation. He also provides resources and referrals.

“We strategize on whether there is someone on the court that the judge is close to, a friend or colleague, who might be in a better position to approach the judge in a way that is not as threatening,” he says.

In addition to its other initiatives, the wellness committee hosts a biennial conference at which judges who are approaching eligibility for senior or recall status or retirement learn about benefits and talk to judges who have transitioned. It also offers a biennial training that brings medical professionals in to present chief judges with new research on cognitive impairment.

David Sellers, the spokesperson for the Administrative Office of the U.S. Courts, confirms that many courts have their own wellness committees, programs or services.

“While all courts share an interest in the health and well-being of judges, each circuit has its own needs and other considerations and variables that are reflected in its approach to physical and mental wellness,” he says.

The Judicial Conference of the United States, the federal judiciary’s policymaking body, agreed in 2011 to encourage circuit judicial councils to consider establishing wellness committees that would both promote health and wellness and provide information on retirement issues.

Chief Judge Priscilla Owen says the 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals at New Orleans “has given considerable thought and attention to issues that may arise if and when a judge is, or may be, disabled or impaired.”

The 5th Circuit Judicial Council appointed a committee to make recommendations, and as a result, directed each district to implement a judicial impairment protocol. While protocols vary, Owen says they provide chief judges with informal mechanisms to address judicial disability or impairment “in a confidential, nonadversarial manner.”

She adds that members of the public or bar cannot use these protocols to file a complaint about a judge. Those procedures are available under the Judicial Conduct and Disability Act, and she says each of those complaints is reviewed thoroughly.

According to Fix the Court, a nonpartisan court transparency group, the 10th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals at Denver created a wellness committee based on the 9th Circuit’s model in 2009.

The Boston-based 1st U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals and Philadelphia-based 3rd U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals also have committees.

Gabe Roth, Fix the Court’s executive director, says the federal judiciary should establish a nationwide program to address cognitive impairment.

“If you are the head of the committee, you can set the policy for all 13 circuits,” Roth says. “It’s better if there is a national policy, because an aging judge in Missouri and an aging judge in Idaho could benefit from the same policy.”

Hamilton sees it differently. She says courts that create their own procedures can be more proactive and avoid the federal disability statute’s often-cumbersome process.

As an example, she says, the Northern District of California has implemented a protocol for age-related disability.

It features a “buddy system,” in which all judges designate someone the chief judge can contact if doubts arise about their physical or mental ability.

“The judges in my court were willing to agree to having a protocol because we like the idea of people we know and work with resolving our issues as opposed to judges on the Judicial Council or Judicial Conference who don’t know us personally,” Hamilton says.

Changing the conversation

As shown by the 9th Circuit, the question of whether judges should submit to regular cognitive exams is receiving more attention.

Shen, who in addition to his work in Minnesota serves as the executive director of the Massachusetts General Hospital Center for Law, Brain & Behavior, focused on this issue in a recent article in the Ohio State Law Journal.

He suggests that if federal judges undergo mandatory—but confidential—cognitive assessments every five years after joining the bench, they will gain valuable information that helps guide decisions about their future.

He contends this solution is “palatable politically,” since it prioritizes privacy—not even a chief judge would see results.

“It might have made sense 50 years ago, maybe even 30 years ago, to say we’re just going to let judges figure it out on their own,” Shen says. “But medicine and science have advanced so much over the past few decades, and although we have multiple tools for detecting dementia, we’re not harnessing that in the law.”

Judith Edersheim: “Just because you can’t find your keys doesn’t mean you’re suffering from dementia.” Photo courtesy of the Massachusetts General Hospital Center for Law, Brain & Behavior

Judith Edersheim works with Shen at the MGH Center for Law, Brain & Behavior. As its co-founder and co-director, she also studies aging judges and warns that cognitive testing might not tell the whole story.

While judges may see improvements in such metrics as language, vocabulary and general knowledge as they age, she says they will see the same declines in attention, working memory and information processing as others in their age groups.

And these declines don’t necessarily correlate to impairments in activity, Edersheim notes.

“Normal aging shouldn’t be so stigmatizing,” says Edersheim, who is also an assistant clinical professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School. “Just because you can’t find your keys doesn’t mean you’re suffering from dementia. Everyone is afraid, and no one wants to be pigeonholed or characterized based on impressions.”

She encourages the legal profession to consider supporting aging judges in the same way the medical profession supports aging physicians. As an example, she says, judges could transition into policymaking or teaching roles where they can use their skills in different ways.

Shen agrees, saying the conversation too often focuses on whether judges should continue working or leave the bench entirely.

They have other options, including moving to another docket or hearing different cases.

“It starts with reframing the question to: What are the key judicial functions you need to carry out?” he says. “And what are the cognitive skills and abilities you need to carry out those functions?”

Staying sharp

As a former member of the ABA Commission on Lawyer Assistance Programs and former chair of its Judicial Assistance Initiative, David Shaheed has done his fair share of research on aging. He has found older adults enhance their well-being by engaging in physical and mental activity and social interactions.

Now 73, Shaheed retired from the Marion County Superior Court in Indiana in 2014 but continues to work as a senior judge to stay sharp.

Modern technology can help judges with mobility issues. “You don’t have to be in a physical space to do the job,” Senior Judge David Shaheed says. Photo courtesy of David Shaheed.

“We have been talking for years about the whole concept of wellness, and it’s a slightly different take on the traditional notion that you work for 25 years, get a gold watch and then play golf or go fishing,” Shaheed says.

“From what I understand, it’s not really healthy to stop doing stuff,” he adds. “One of the things that I love about being a judge is the interaction with people, and quite honestly the mental challenge of figuring things out.”

By evaluating healthy older adults, Miller, the head of the study involving the 9th Circuit, also hopes to better understand when underlying neurodegenerative diseases begin to emerge and if they could be treated in the next few years.

He has worked closely with Hamilton and other judges but was still surprised by how many agreed to participate in the study. He views the chief judge’s leadership as the impetus.

“This has influenced massively the 9th Circuit, but it’s also beginning to influence other judges across the country,” Miller says. “Because so many of them are older, thinking about brain wellness is just absolutely critical.”

Hamilton understands that many judges don’t like to discuss cognitive decline for the same reason they don’t like to talk about advance directives. But it’s a worthwhile topic that she will continue to put before them.

“I think it’s hard for people because it does make them face their own mortality,” Hamilton says. “It’s personal. It’s sensitive. But it’s important for judges to talk about it.

“To hear that other people in your own cohort, people who are your colleagues, are having the same kinds of challenges, it inures to a more open conversation.”

This story was originally published in the Dec/Jan 2020-2021 issue of the ABA Journal under the headline: “Benching Judges: Knowing when it’s time to hang up the robe.”

Write a letter to the editor, share a story tip or update, or report an error.