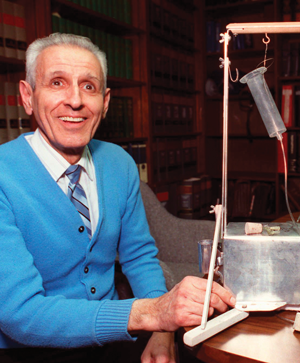

Nov. 20, 1998: Kevorkian's last suicide

AP Photo/Richard Sheinwald

On a Sunday evening in 1998, viewers of the perennially popular CBS news program 60 Minutes witnessed a videotaped death. Whether in horror or fascination, as many as 22 million people watched as 52-year-old Thomas Youk, withered from amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, accepted three injections from Jack Kevorkian, a controversial Michigan physician known colloquially as Dr. Death.

For more than 40 years, he made a career of provoking both the law and the ethics of the medical profession as a proselyte for assisted suicide. By the time 60 Minutes aired his tape of Youk’s death two months earlier, Kevorkian had already assisted in scores of suicides. He had lost his license to practice medicine in Michigan and California. Legislators wrote laws to help prosecutors stop him. Jurors struggled to balance Kevorkian’s brash moral certainty with the human suffering he claimed to relieve.

Born Murad Kevorkian, his parents were refugees of the 1915 Armenian genocide. In 1952, he graduated from the University of Michigan medical school, where he’d long shown a fascination for the subject of death and a predilection for challenging traditional medical values. In 1959, he suggested in a major political science journal that condemned prisoners be allowed to choose medical experimentation as a means of execution. The idea brought him professional contempt and an invitation to leave his post at the University of Michigan Medical Center. After a few years as an itinerant pathologist, Kevorkian spent the 1970s exploring art and music, even dabbling with a film on Handel’s “Messiah.” But on his return to Michigan in the early 1980s, he became enthralled with the implications of euthanasia as it had begun to be practiced in the Netherlands.

On the topic of physician-assisted suicide, Kevorkian became more than an advocate. He developed two “death machines”—the Thanatron and the Mercitron—allowing death-determined patients to administer their own suicide by intravenous injection or poison gas. Moreover, he sought serious financial backing for the development of suicide clinics, where individuals seeking to end their life could connect with health professionals who would help them die.

In 1990, Kevorkian’s efforts became more than philosophical. Janet Adkins, a patient with Alzheimer’s disease, asked him to allow her to use his Thanatron. In a makeshift death clinic inside Kevorkian’s Volkswagen van, Adkins became his first suicide assist. For that, Kevorkian was charged with murder, a charge later dismissed.

In 1991, he was present at the deaths of two women—Sherry Miller and Marjorie Wantz—and was again charged with murder. Kevorkian was tried and acquitted in May 1996, but by that November he had been present for the suicides of an estimated 46 people.

After three jury acquittals, a mistrial before a fourth and at least five dismissals by Michigan judges, Kevorkian became increasingly emboldened: a public character—part thanatological moralist, part carnival barker in a sideshow of death. He dressed in colonial garb during one of his trials, taunted juries to convict him, and at one point, assisted in a suicide between sessions of his own murder trial.

With the 60 Minutes showing, however, all that changed. For the first time, Kevorkian had not simply assisted in a suicide but actually had administered the drugs that caused Youk’s death, all captured on a video he made himself. Three days later, Kevorkian was charged, once again, with murder.

On March 26, 1999, Kevorkian was convicted of second-degree murder. Sentenced to 10 to 25 years in prison, he served more than eight before being released in 2007 on the promise he would no longer assist in suicides.

In 1997, Oregon passed the Death with Dignity Act that permitted physicians to prescribe lethal drugs for terminally ill patients who meet a strict set of standards. Since the law’s passage, more than 1,545 qualified patients have received prescriptions for fatal drugs. Of those, 991 ultimately chose to die by their own hand.

Write a letter to the editor, share a story tip or update, or report an error.