Guardians of the Sixth Amendment

Editor’s note: The following short story was the winner of the sixth annual ABA Journal/Ross Writing Contest for Legal Short Fiction.

Sonya burst through the door, a large fraying black purse stuffed to the brim on one shoulder, a briefcase overflowing with papers on the other, a file clutched in her left hand, and an extra-large coffee in her right. Her gray suit was wrinkled, a stain slightly visible on the pale blue shell underneath. The sensible black heels she donned every day, perfectly scuffed and aged, on her feet. Her graying, curly hair was untamed, made worse by the glisten of sweat coating her face and neck from the Southern humidity.

“I know. I know. I’m late.” She called over her shoulder to her paralegal, Kate. “Sarah had a dentist appointment this morning, and Dave had an early meeting, so I had to take her.” She beelined for her office down the hallway, Kate following closely behind. “What’s on for today? I can’t remember.” The women barreled past their co-workers, her gaze affixed only on her destination.

Sonya wrestled open the door of her cramped government office and switched on the flickering fluorescent lights. Somewhere beneath stacks of files was a desk, chairs and a computer. But at first sight, the room looked more like a paper graveyard. Atop a bookshelf in the corner stood three picture frames—one showing a couple in their early 30s at the beach playing in the sand with two toddlers; another, a family photo taken at Disney World; and the last, the senior picture of Sonya’s oldest daughter, Tiffany, who would graduate in three months. Timeworn children’s artwork was haphazardly taped to the walls and the sides of a filing cabinet, with “I LOV YU MOMY” in crayon scrawled on most of the pages.

Dumping her bags onto the floor and unceremoniously plopping the file in her hand onto one of the many piles, Sonya turned her attention to the barely visible computer screen that woke at her touch. Kate, removing from a chair a pile of files as tall as her arms were long, took a seat and pulled out her calendar. “You have five initial appearances in 30 minutes in front of Judge Bridgeman. Downstairs in Courtroom 3. And two detention hearings. But we haven’t heard back from the third-party custodian in Mr. Young’s case, so you may want to have him waive. Then you have appointments down at the jail.” She handed Sonya a printed schedule. “And tomorrow you’re covering court in New Maple, 10 arraignments, three initial appearances and three sentencing hearings.”

Sonya’s face remained unchanged as she logged into her email, 60 new messages awaiting her. Just another day working in the federal public defender’s office. The guardians of the Sixth Amendment could barely keep their heads above water, but the chaos was their normal. And with the new administration, the caseload seemed to have doubled in only a few months. It was all she could do to just go through the motions, let alone zealously advocate for each of the nameless, faceless files that endlessly piled up around her.

“OK. Thirty minutes, you said.” Sonya took a generous sip of her now-cold coffee, reading through the list of defendants whose liberty depended on her that day.

A blinking light emanating from the telephone caught Sonya’s attention. Pressing the button, the robot in the machine answered, “You have 15 new messages.”

“Fifteen?” She looked incredulously at her paralegal. “I was here until 8 last night, and it’s only 9:15.” Each of the voices that spoke to her through the machine were clients calling from jails and prisons located throughout the state, wanting to know the status of their cases: “Did you talk to the government like I told you?” “Ask for a continuance next week.” “I wanna appeal my plea.” “How the hell did I get 60 months? You promised I would only get probation!”

Sonya jotted notes on a crumpled legal pad that had maybe five blank pages left, the remaining pages bursting with handwritten text margin to margin. Once the messages concluded, Sonya turned to her paralegal and gave an exasperated smile. “Thanks, Kate.”

. . .

The Byrum County Jail was truly her least favorite place in the world. It was dark and damp—everything you would expect of an old county jail that had not been updated since its creation. Sonya flipped through the five redwells resting in her lap as she waited to be called to meet with her clients—drugs, drugs, drugs, drugs and drugs. She estimated probably 80 to 85 percent of the cases she handled were “drugs and guns” cases. Those cases were the easiest for the government to prove—you either had drugs or guns on you, or you didn’t; you either had permission to have those drugs or guns, or you didn’t. And then add a prior felony on top of it, case closed, Not much wiggle room for her to argue.

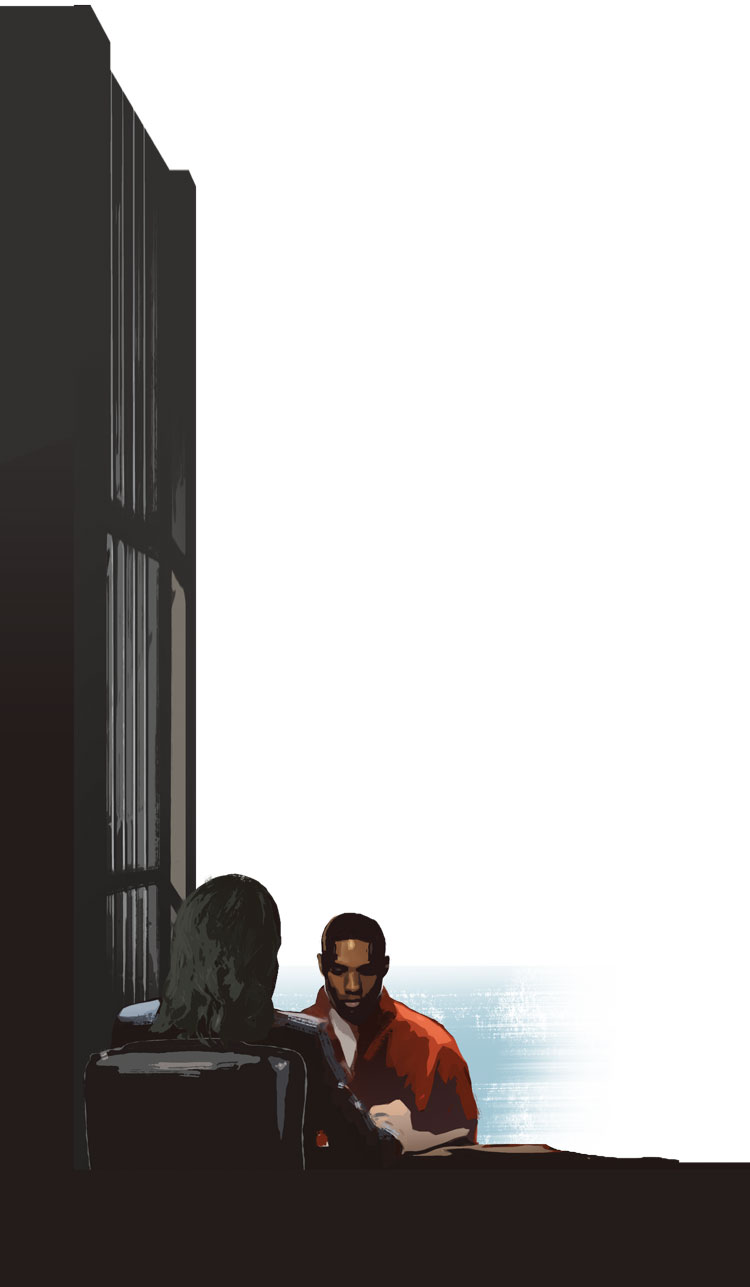

Illustration with David Owens.

“Sonya Church.” A uniformed officer stood in front of a door that was ajar, peering at her over crooked reading glasses, an old wooden clipboard in his hand. Grabbing her bags and files, she stood and followed the officer to the all-too-familiar meeting room. The room contained only a table, two chairs and a window where the officers monitored their meeting from the hallway.

She took a seat and opened the first file in her stack. Da’Vonte Moore—a 23-year-old black male who was picked up after he sold a confidential informant heroin three times over a span of two weeks. It was his fourth time being picked up for selling drugs, but this was the first time he had been picked up by the feds. An unregistered firearm had been found in his waistband when he was arrested, and about 100 individual baggies of heroin were found in his car: Drug Trafficking 101.

She heard the sound of chains gradually growing louder as Da’Vonte made his way down the hallway toward the little room. He barely made eye contact with her as the guards sat him in the chair, the handcuffs and leg chains remaining in place.

“Officer, you can take those chains off.” Sonya hated counseling clients who were chained like zoo animals. It made the small, dim room seem smaller, and the rattle of the chains would often interrupt her train of thought.

“Sorry, ma’am, no can do. There was an incident earlier today where this gentleman attempted to assault a guard. We’ve been instructed that the chains stay on.”

“Man, I ain’t assault nobody! Y’all know that’s some bullshit.” Da’Vonte’s face curled into an exasperated and angry look as he shook his head at the officer exiting the room. He finally turned his attention to his attorney. “I ain’t assault nobody,” he repeated.

“All right, Mr. Moore. Just calm down. I’m Sonya Church from the federal public defender’s office, and I represented you at your initial appearance in front of Judge Sunstrom last week.”

“I remember you, Ms. Sonya.” Da’Vonte’s left fingers attempted to rub the parts of his right wrist being constrained by the handcuffs. “Damn, these are tight.”

“I’m here to talk to you about your detention hearing on Wednesday. Basically, since the government moved to detain you pending the outcome of your case, you are entitled to what’s called a detention hearing, where we hopefully show the judge that you can be trusted to attend court and follow the laws while we figure out what to do with your case. You understand?”

“Yeah, kinda. Can’t I just plead to probation or whatever? That’s what I’ve done before.”

“Well, Mr. Moore, before you were in state court. This is a federal case. The rules are totally different. You definitely are not getting probation. Honestly, you’re looking at 10 to 40 years in a federal prison for this.”

Da’Vonte’s attention left his right wrist and shot to his attorney’s face. Then he started laughing. “Shit, you playin’, Ms. Sonya. I only sold a dime or two. I even took a discount for that shit.”

“I’m not playing. They claim to have audio and visual from the guy you sold to that clearly shows you sold him heroin three different times. There will be no doubt in any juror’s mind that not only are you guilty of these crimes but that it’s very probable you’ll continue to sell heroin in the community if they let you out. And no one wants to let a guy out who is going to sell their kids or their siblings or their spouses heroin. Especially discounted heroin.”

“Man, I knew that guy was a snitch. I could feel it.” His head fell into his cuffed hands. “So what you gon’ do, Ms. Sonya?”

“Well let’s take it one step at a time. At the detention hearing, the government will probably have the lead agent on your case testify about the evidence against you. And then we will offer evidence indicating you can be released pending the end of the case, and that you will not be a danger to the community, and you will come to court when you are supposed to. That usually requires what’s called a ‘third-party custodian.’ That’s somebody who will baby-sit you while you’re out, make sure you’re not breaking the law, that you’re in the house when you’re supposed to be, that you get to court. Things like that. Can you think of anybody to do that? Your mom or a grandma or a girlfriend?”

Da’Vonte thought for a few seconds. “I guess you could try my mom. But she works a lot down at the old people’s home. So I don’t know if she could get off work. My grandma maybe could do it.”

“All right, tell me about your grandma.” Sonya retrieved her dilapidated legal pad and pen.

“She’s 75, on disability, has a bad heart.”

“I’m sorry. My mom also has some heart problems.”

“Yeah, she has trouble breathing. Can’t walk too long without having to sit down.”

“Bless her. What’s her living situation like? Have you ever lived with her?”

“Um, she lives downtown, off Bleecker. My aunt and her three kids live with her. I lived with her for a few months when I was little when my mama didn’t have a job. But that was like 10 years ago.”

“OK, and is there room for you to live there? How many bedrooms does she have?”

“I mean, I guess she could make room. I could sleep on the couch or the floor or something. She only got two bedrooms, so my cousins all sleep on the floor, usually.”

This wasn’t the first time Sonya had heard of this type of living situation—multiple family members piling into small houses where there was no room for them. And she knew judges were often unwilling to put a drug dealer that carried a gun into a small home with an elderly matriarch and children living under the same roof.

“Have you ever had a job? Did you graduate from high school?” She had seen judges let out a guy like Da’Vonte if they had a job to go to or college classes they needed to attend. But few ever did.

“Nah, I tried to work at that Burger King on 3rd and that Food Lion on 15th when I was 17, but they ain’t hire me. My mom told me I needed to get a job to help her with some of the bills and groceries and stuff. I’d just been picked up for my first charge—I had a blunt on me and got hit with simple possession—so I think they ain’t wanna deal wi’ a criminal. But I did graduate from high school. Just can’t do much with that diploma now.”

“Good for you for finishing high school. So many of my clients get sucked into that cycle. Once you pick up one charge, a lot of employers go running, and then selling drugs becomes the only viable way of making a living and supporting your family. You’re definitely not alone in that.”

“Yeah. But I won’t do that shit no mo’. I don’t wanna go to prison!”

“I can tell you in my experience, based on your charges and the type of environment you would be in at your grandmother’s house, that a judge, especially Judge Sunstrom, is not going to let you out. Can you think of anyone else? Maybe we can see if your mom can get Wednesday off from work?”

Da’Vonte sat quietly, thinking. “Nah, I can’t ask her to do that. She got my brothers and sisters to worry about. Well, can’t we just try with my grandma? At least see what the judge says?”

Situations like these were always tough for Sonya. She knew what Judge Sunstrom would do: She would sit on the bench quietly, take sparse notes and ultimately keep Da’Vonte detained.

Sonya’s clients did not have the wealth of experience she had and the jadedness that came with it. It was hard sometimes, reminding herself that, while this was her thousandth time going through this process, it was the first for the client. They always believed that their cases were unique and special, and that a judge would see them for who they really were. Sonya knew each client’s case was just another box on the speeding conveyor belt that was federal drug prosecution. All the boxes were the same, and they were all going to the same destination. But out of the two people in the room, only Sonya could appreciate that harsh reality.

“Well, it’s your right to decide what you want to do. But as your attorney, I’d advise you to waive your detention hearing. I can tell you unequivocally that you will be detained. No judge will let you out to those conditions. Frankly, the hearing would be a waste of time.”

“Waste of time? If I got 10 to 40 years in prison waitin’ for me, what else do I got but time? I don’t give a damn about wastin’ no judge’s time or no prosecutor’s time. They got a job ’cause of me.”

Sonya was really talking about wasting her time, a vision of her office packed full of files coming to mind. She had four other defendants to talk with that day about their detention hearings, all of which were scheduled for Wednesday. Frankly, the more hearing waivers she got, the better.

“It’s your decision, Mr. Moore. I’ll do whatever you like, but I want to realistically set your expectations. You need to go into that hearing expecting to fail, do you understand?” Subtle persuasion sometimes worked—don’t tell the client what to do, just simply make them think it was their idea.

“That’s fine. Let’s do it.”

Well, that didn’t work.

. . .

Ross Award winner sees the honor in public defenders' work

Runner-up essay: Still There in the Ashes