April 13, 1963: Sam Sheppard seeks a new trial

Defense attorneys William Corrigan and Arthur Petersilge with Dr. Sam Sheppard in court in 1954. Associated Press photo.

ABC aired the first episode of The Fugitive in September 1963, dramatizing the saga of Dr. Richard Kimble, a fictional physician who escaped custody while facing the death penalty for the brutal murder of his wife. The hit show marked a shift in fortune for Dr. Sam Sheppard, the Ohio surgeon on whose case the show was based.

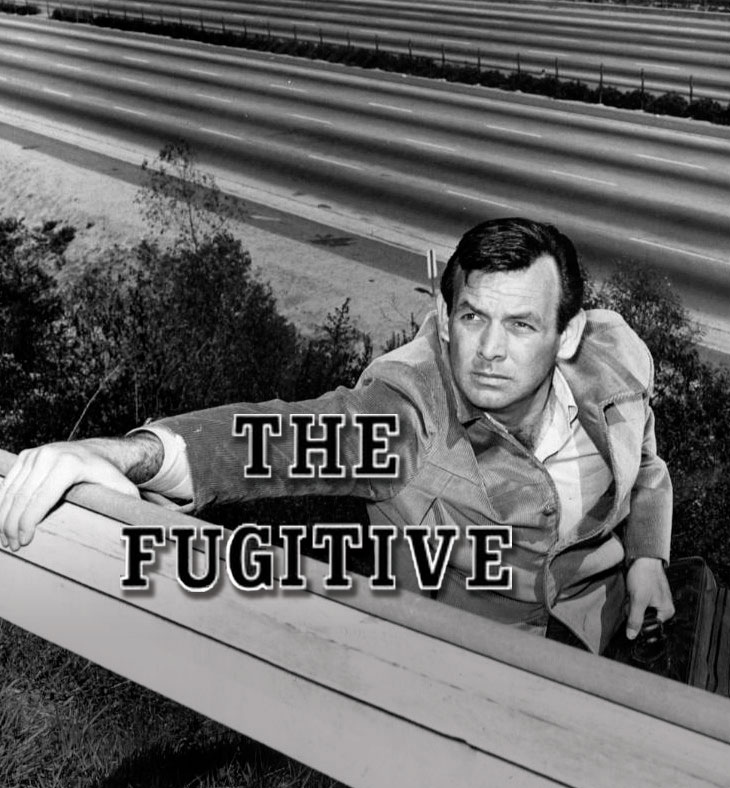

Actor David Janssen plays Dr. Richard Kimble in “The Fugitive”, which was based on Sheppard’s story. Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

On April 13, five months before The Fugitive debuted, Boston lawyer F. Lee Bailey filed a writ of habeas corpus in federal court challenging the fairness of the extraordinary 1954 trial in which Sheppard was convicted. By any measure, his trial for the bludgeoning death of his pregnant wife, Marilyn, had been a spectacular media event. But Bailey argued that prejudicial publicity in the case had trampled the delicate boundaries between a right to public information and Sheppard’s right to a fair trial.

Before dawn on July 4, 1954, Sheppard had called a friend—the mayor of Bay Village, the Cleveland suburb where the Sheppards lived, to report that an intruder had murdered Marilyn. The mayor arrived with the police a few minutes later to find the doctor injured and disoriented.

Sheppard recounted a rambling story: He had fallen asleep watching television, was awakened by his wife’s screams upstairs and twice confronted a “bushy-haired” man who had beaten him—first in their bedroom, then outside the house after Sheppard took chase.

The doctor’s story sat poorly with police and the county coroner. To them, the bludgeoning suggested an angry confrontation and the crime scene a robbery staged for their benefit. They quickly focused on a relentless effort to make Sheppard confess.

Media attention was equally relentless. Police seized Sheppard’s home but allowed access to a stream of news crews and curious onlookers. Urged by local newspapers to do so, police interrogated Sheppard at his hospital bedside without his lawyer present. When a front-page editorial demanded an immediate inquest, coroner Sam Gerber obliged, giving Sheppard and his lawyer one day’s notice.

In a televised, three-day inquest before a packed school gymnasium, Gerber interrogated Sheppard about the intimacies of his marriage. When his lawyer William Corrigan objected, Gerber had him removed to the roar of an approving crowd. Just days later, a headline in the Cleveland Press screamed: “Why Isn’t Sam Sheppard in Jail?”

By that evening, he was.

With a change of venue denied, the carnival continued at trial. In court, the press sat inside the bar, able to hear and report the whispering of jurors and lawyers, and able to scrutinize evidence before it was presented. Names and addresses of jurors and witnesses were published in the newspapers; their families were interviewed. Sensational articles promised “bombshell testimony” that never materialized. By the time Sheppard was convicted, only five months after the murder, the presumption of his guilt in Northern Ohio had long been regarded as fact.

Three months after the habeas was requested, a federal judge released Sheppard pending a new trial. Though it was reversed on appeal, Sheppard remained free to attend Bailey’s U.S. Supreme Court oral arguments in Sheppard v. Maxwell. In June 1966, writing for an 8-1 majority, Justice Tom Clark detailed the barrage of “virulent and incriminating” media coverage of the Sheppard investigation and excoriated the failure of the trial court to control media access to jurors.

Time and television helped temper public animus in his case. And by August 1967, when The Fugitive proved Kimble’s innocence to a record TV audience, Sheppard had been retried and found not guilty by a Cuyahoga County jury.

After a litigation-plagued return to surgery, he had a brief career as a professional wrestler. His ring moniker was “the Killer.” Sheppard’s freedom was short-lived. He died in 1970 due to complications of alcoholism.

Write a letter to the editor, share a story tip or update, or report an error.