Duped: New book explores what makes people confess to crimes they didn't commit

Photo courtesy of Rowman and Littlefield

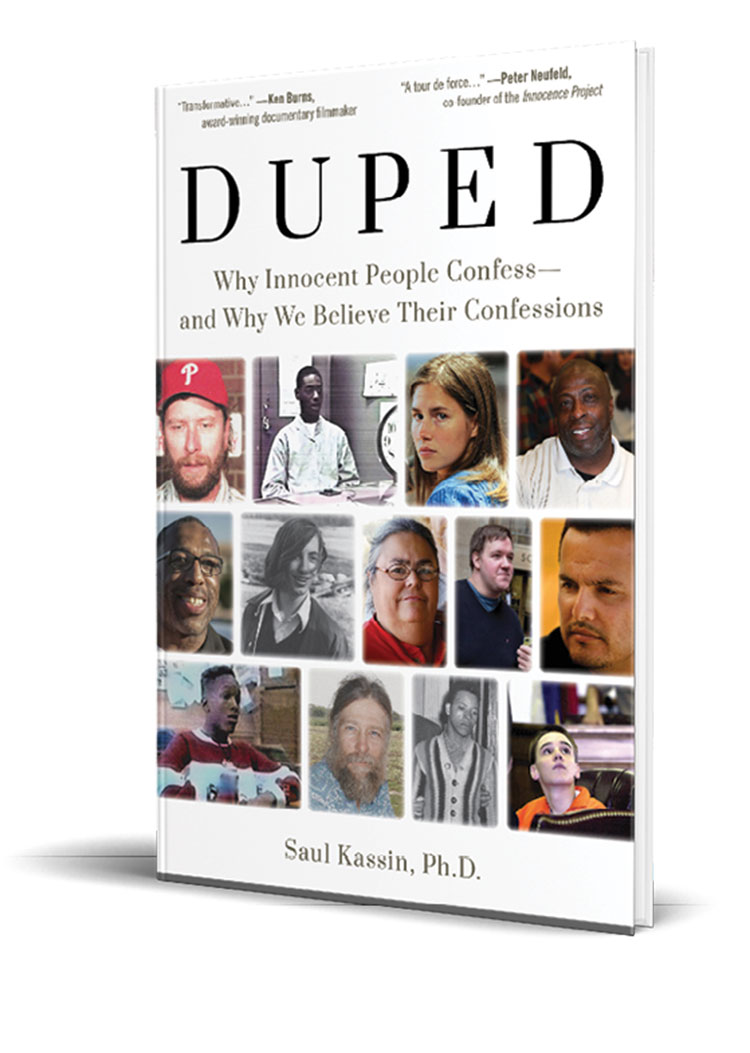

Hanging on a wall in Saul Kassin’s office at John Jay College of Criminal Justice in New York City are photos of 28 people who confessed to crimes they didn’t commit. He periodically updates this collection, which he calls his “wall of faces,” as more false confessions come to light.

“I put up this wall because the images are hard to escape. There are men, women, people of different ages, different colors, different ethnic backgrounds, different countries,” Kassin says. “These are people from all walks of life. And the one thing they all have in common is that they gave a false confession.”

Kassin, a distinguished professor of psychology, shows these images during talks and lectures around the country. “Everyone’s first reaction when I talk about false confessions is, ‘What is wrong with those people?’”

Nothing, he says: “This can happen to anyone. This can happen to you.”

Kassin has written a new book exploring this phenomenon. Duped: Why Innocent People Confess and Why We Believe Their Confessions (May 14; Prometheus Books), chronicles his journey as a social psychologist who became fascinated and disturbed that innocent people can be manipulated into false confessions. He’s considered a pioneer of in the study of false confessions.

Over the years, Kassin has interviewed and befriended many who appear on the wall—people such as Peter Reilly, who in 1973 at the age of 18 discovered his mother’s body in their Connecticut home. Under pressure from police who confronted the teenager with so-called lie detector results, Reilly confessed nearly 24 hours after the murder. He gave what Kassin describes as an internalized false confession—one in which suspects come to believe they actually committed the crime. Reilly was tried and convicted, but he was exonerated two years later.

“As far as courts are concerned in this country, the confession is the perfect gold standard,” Kassin says.

That’s because people are reluctant to believe someone would confess unless they were beaten, tortured and coerced.

“The problem is the word coercion. It implies that the way you get an innocent person to confess is that you threaten them, beat them, pound the table, badger them, deprive them of food,” Kassin says. “It sometimes happens that way, but that’s not necessarily the way this goes down. It happens through psychological trickery and deceit.”

Kassin attributes many false confessions to detectives trained in the Reid method of interrogation, which he first read about 40 years ago. “The social psychologist in me was horrified,” he writes in the book. “I could not help but wonder what effects these tactics had on innocent people.”

The book takes a critical look at the Reid technique, developed by John E. Reid & Associates Inc. of Chicago. Kassin says the Reid technique teaches interrogators that they can tell if a person is lying through a friendly, initial encounter called a Behavioral Analysis Interview. If police believe a suspect is lying, they move to the next phase of questioning. “This is where the detective launches into accusations, trickery and deceit—all aimed at a full confession,” Kassin writes.

Police, even well-intentioned, can put on blinders once they believe they have the right suspect. “In social psychology, one of the cardinal principles is that once a person forms a strong belief, there’s almost nothing you can do to change it,” Kassin says.

Kassin finds this troubling. He’s seen cases, for example, in which police formed judgments based on how people behaved after the loss of a loved one or friend. “A lot of times, the investigators look at their demeanor and say something’s off,” Kassin says. “Well, yeah, something’s off. This is a person traumatized by the loss of a loved one. There is no one way to grieve, to react to trauma.”

Take the case of Marty Tankleff, who awoke to find his parents mortally wounded in their Long Island home in 1988. A detective decided the 17-year-old wasn’t showing enough emotion and labeled him a suspect. They interrogated him for hours, lied about evidence and faked a phone call from the hospital in which Tankleff’s father supposedly said that his son attacked the couple. His father never regained consciousness and died weeks later.

Tankleff wondered whether he blacked out or broke down somehow. He confessed and was convicted solely on his statement, which he never signed. He eventually was exonerated in 2008 and later became a lawyer.

Kassin notes a key factor that led to Tankleff’s confession: the 1969 Supreme Court decision in Frazier v. Cupp, which made it lawful for police to lie about evidence while interrogating suspects. Kassin points out that such leeway makes young suspects especially vulnerable. “There isn’t a psychologist on the planet who doesn’t understand the risk of doing that and wouldn’t see the risk to an innocent person,” he says.

In interviews with exonerees, Kassin learned that many confessed because they assumed evidence eventually would show they didn’t do it. “They become complacent and believe innocence will set them free,” he says. “They say, ‘Well, I didn’t need a lawyer, I didn’t do anything wrong.’”

Suspects who confess and later recant have had an uphill battle, although the advent of DNA technology and advanced forensics has opened doors to help prove their cases. “When the Innocence Project was founded in 1992, that was a game changer. That just altered everything,” Kassin says.

Founders Peter Neufeld and Barry Scheck, along with a dedicated group of lawyers, sparked a movement that has since uncovered more than 100 wrongful convictions based on false confessions and inspired the creation of innocence projects at colleges and law schools across the country.

Kassin is encouraged by reforms among some states that require the recording of interrogations and ban lying about evidence to juvenile suspects. But it’s not enough. He says loopholes allow police to turn off cameras, claim equipment malfunctions or say no cameras were available.

Kassin sees this scenario ensuing: “And then off-camera, someone confesses,” he says. “There should be a no-excuse policy. If the whole thing is not on camera, the confession should not be admissible.”

Write a letter to the editor, share a story tip or update, or report an error.