Missing Benchmarks: Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders are still underrepresented in the judiciary

(Illustration by Sara Wadford/Shutterstock)

In the mid-1990s, Susan Oki Mollway was working as a civil litigator at Cades Schutte Fleming & Wright in Honolulu when a vacancy arose on the U.S. District Court for the District of Hawaii.

Mollway didn’t run in political circles and wasn’t sure she would be considered a serious contender. But with the support of her colleagues, she decided to throw her hat in the ring.

“I was about the right age to be credible, and they like to appoint federal judges who are fairly young,” says Mollway, a Japanese American who was then in her 40s. “And Hawaii has a very diverse population. I would not be the first woman or the first Asian to be appointed to Hawaii’s federal bench. But I would be the first Asian woman.”

To Mollway’s surprise, she also would be the first Asian American woman in the country to serve as an Article III federal judge. Per the U.S. Constitution, Article III judges, which include those on the U.S. Supreme Court, courts of appeals and district courts, are nominated by the president and confirmed by the Senate. They serve life terms in seats authorized by Congress.

Judge Susan Oki Mollway wrote The First Fifteen: How Asian American Women Became Federal Judges to chronicle the experiences of those who followed her onto the bench. (Photo by Dylan Marcus)

Judge Susan Oki Mollway wrote The First Fifteen: How Asian American Women Became Federal Judges to chronicle the experiences of those who followed her onto the bench. (Photo by Dylan Marcus)“I didn’t imagine there had never been one before me,” says Mollway, who went on the bench in 1998. “When I mentioned it to other people, including judges, they were also astounded. You would think in the late ’90s, surely somebody would have come before me who fit my profile.”

Mollway didn’t have many male peers with similar backgrounds either. The Federal Judicial Center shows 1,250 active and senior Article III judges were serving in 1998. Of all the judges, eight were Asian American and one was Pacific Islander.

While progress has been made in the past 25 years, members of these communities continue to be underrepresented at the highest levels of the legal profession.

According to the National Asian Pacific American Bar Association, 59 of the 870 currently authorized Article III judgeships are held by individuals who identify as either Asian American, Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander. Put another way, about 6.8% of active Article III judges are Asian American, Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander.

These numbers do not include senior judges, who often handle a reduced caseload once they turn 65 and have served at least 15 years—or reach any other combination of age and years of service that equals 80—and leave vacancies that are filled by new Article III judges.

These numbers also don’t reflect the racial and ethnic makeup of the American people. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, Asian Americans, Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders account for 7.7% of the country’s population.

“A bench that is reflective of the vast diversity of the United States—such as in background, life experience and professional experience—is one that can fulfill that guarantee of due process for all and, ultimately, deliver informed decisions,” says Priya Purandare, the executive director of the National Asian Pacific American Bar Association in Washington, D.C. Representation for the Asian American, Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander community, “as well as for all communities of color who have been historically and vastly underrepresented, is critical for our judiciary,” she says.

“Our primary focus has been on the federal bench,” says Priya Purandare of the National Asian Pacific American Bar Association. (Photo by Les Talusan)

“Our primary focus has been on the federal bench,” says Priya Purandare of the National Asian Pacific American Bar Association. (Photo by Les Talusan)Charting the path

When Justice Goodwin Liu joined the California Supreme Court in 2011, he quickly realized few Asian Americans occupied other seats on the bench. He also became aware of “how enormously proud and hungry the community was” to have him, he says.

“It wasn’t really about me but about the idea of an Asian American sitting on the high court of California and, in a sense, spotlighting the issue that there are so few people like me,” says Liu, the son of Taiwanese immigrants and previously an associate dean at the University of California at Berkeley School of Law. “They wanted that example, wanted that role model, wanted something to aspire to.”

Justice Goodwin Liu of the California Supreme Court examined the representation of Asian American and Pacific Islanders in the legal profession in two research studies. (Photo by Sherry Glassman)

Justice Goodwin Liu of the California Supreme Court examined the representation of Asian American and Pacific Islanders in the legal profession in two research studies. (Photo by Sherry Glassman)Liu began examining the career paths of Asian American lawyers, and in 2017, his research evolved into a novel study commonly known as the Portrait Project. Published in part by the National Asian Pacific American Bar Association, the study showed Asian Americans were present in all areas of the profession but mostly missing from the leadership of law firms, federal government and legal academia.

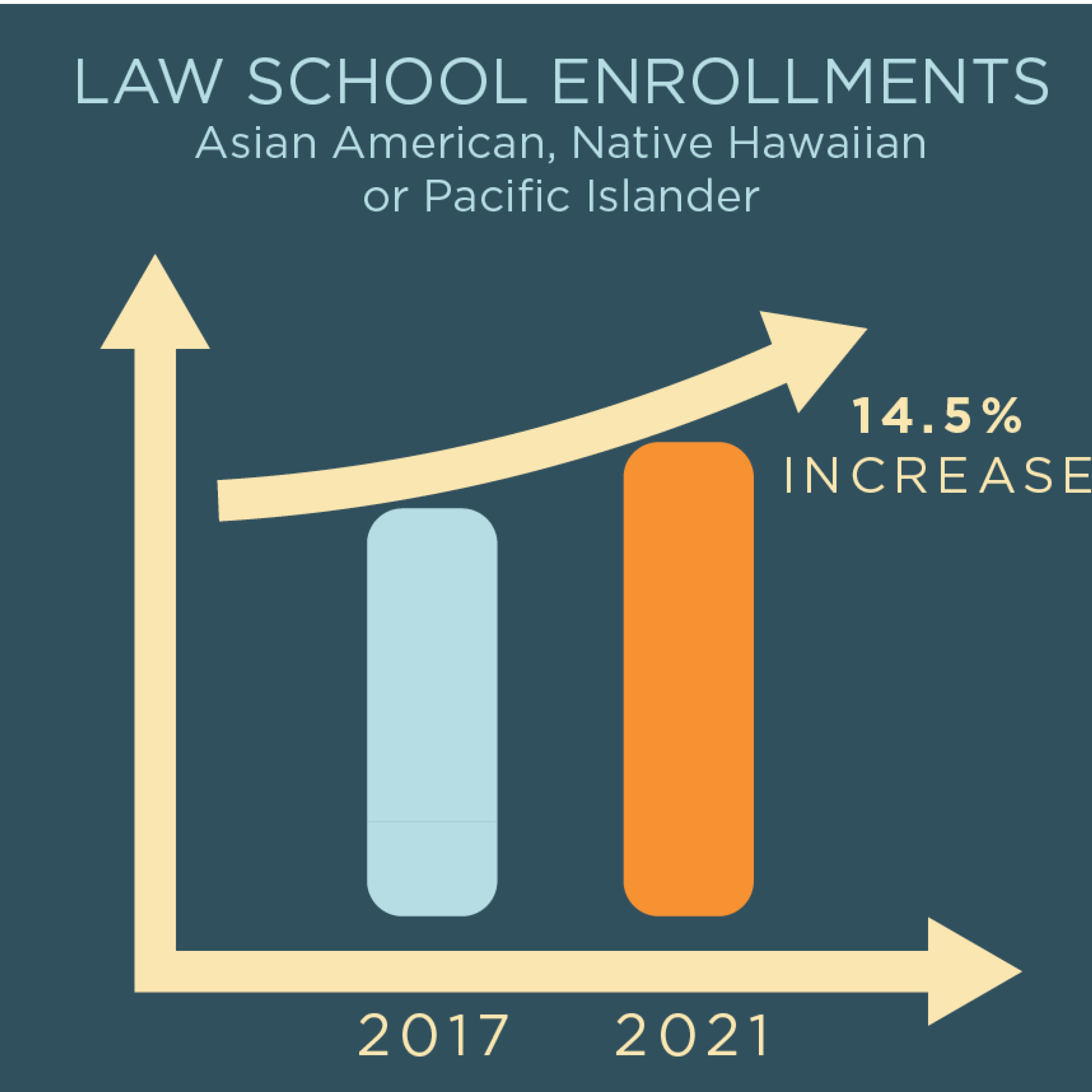

In 2022, Liu assisted with the Portrait Project 2.0, a follow-up study by the National Asian Pacific American Bar Association and American Bar Foundation. It found underrepresentation persisted despite considerable numbers of Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders showing interest in entering the profession. From 2017 to 2021, their enrollment in law schools increased by 14.5%.

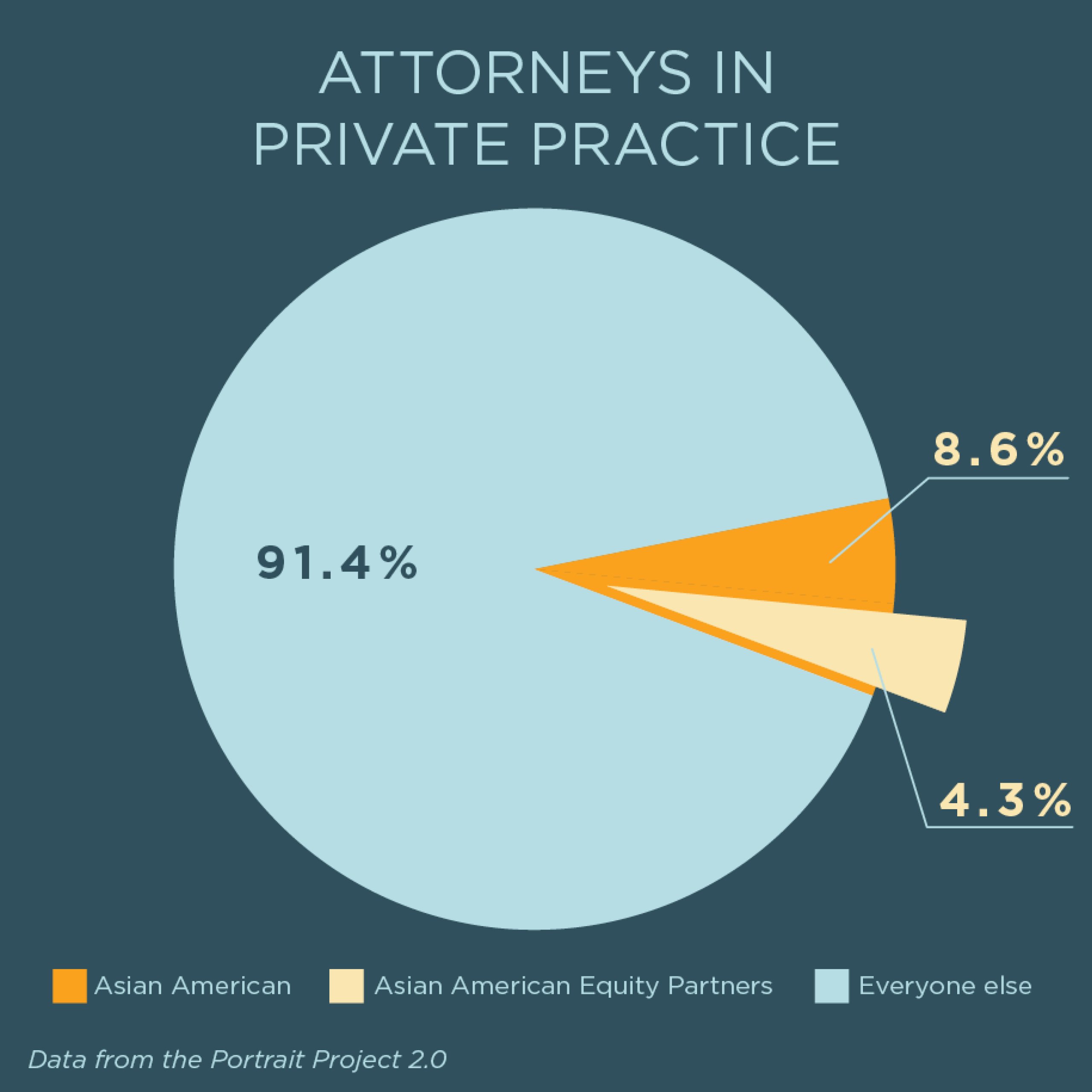

However, while 8.6% of attorneys in private practice were Asian American in 2020, the study found only 4.3% were equity partners. In other leadership roles, only one of 93 presidentially appointed U.S. attorneys and eight of 2,396 elected prosecutors nationwide in 2022 were Asian American. And in state high courts, only nine of 340 judges identified as Asian American.

“Asian Americans have done quite well at getting into good law schools and are getting a strong foothold in virtually every sector of the legal profession,” Liu says. “The difficulty that Asian Americans face is really in advancement. It’s not at the entry level. And I don’t think you can explain this simply by saying, ‘Well, this is a time-lapse thing.’”

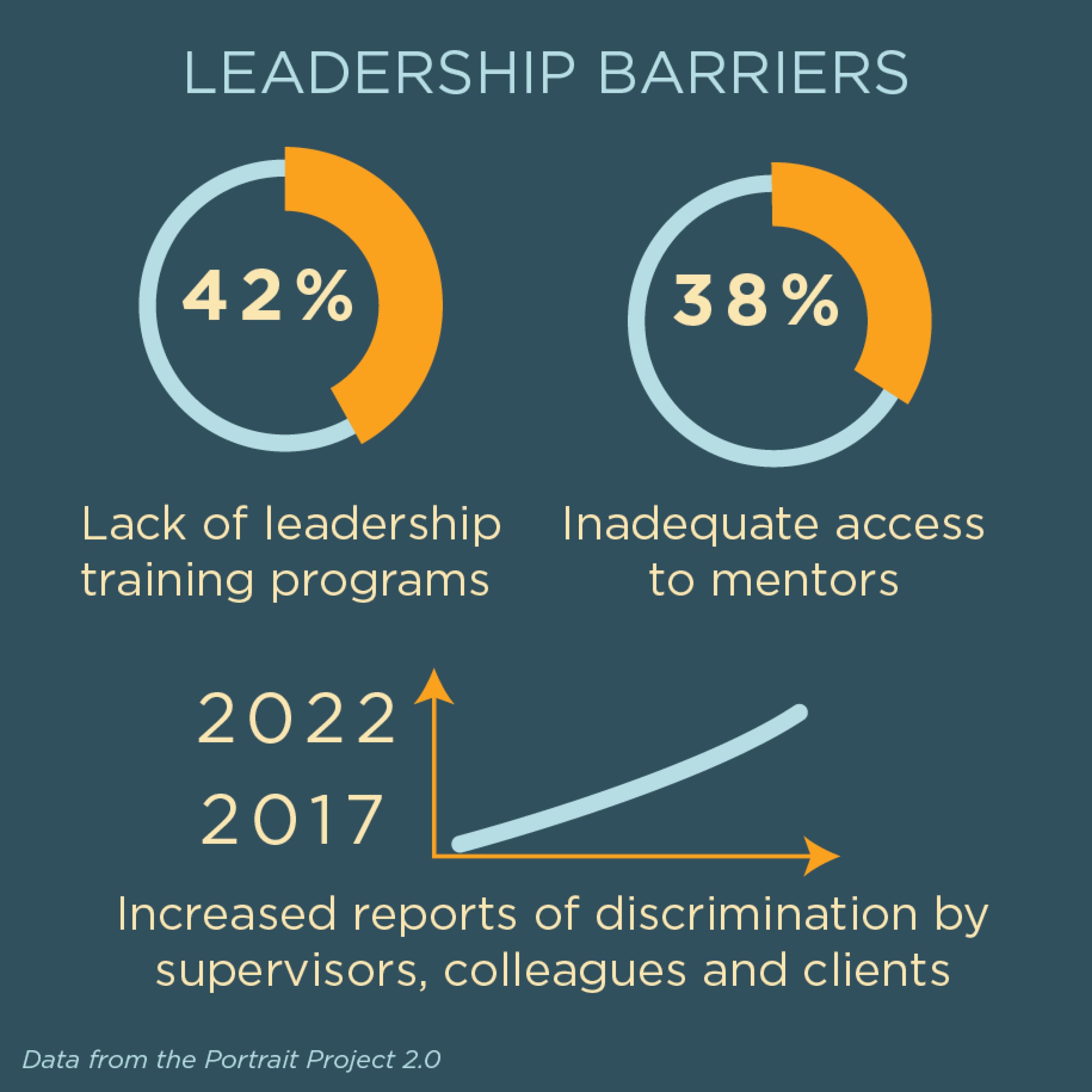

When asked about barriers, about 42% of the study’s respondents cited a lack of leadership training programs, and 38% said they had inadequate access to mentors. More respondents in 2022 also reported discrimination by supervisors, colleagues and clients than in 2017.

Judge Holly Fujie, a 2011 appointee to the Los Angeles County Superior Court, describes her own experience entering the legal profession as a less than welcoming one.

After graduating from the University of California at Berkeley School of Law in 1978, she was the only Asian American at a large law firm in Los Angeles. Fujie, who is Japanese American, says she “could tell stories until the cows come home” about how other attorneys mistreated her.

Nurturing a judicial pipeline for young Asian American and Pacific Islander attorneys is very important to Judge Holly Fujie of the Los Angeles County Superior Court. “If you don’t have people apply, you can’t appoint them.” (Photo courtesy of Judge Holly Fujie)

Nurturing a judicial pipeline for young Asian American and Pacific Islander attorneys is very important to Judge Holly Fujie of the Los Angeles County Superior Court. “If you don’t have people apply, you can’t appoint them.” (Photo courtesy of Judge Holly Fujie)“The thing is, you didn’t want to rock the boat back then,” says Fujie, who in 2008-2009 became the first Asian American to serve as president of the State Bar of California. “You didn’t want to say anything. You were so busy trying to fit in and not have people treat you differently.”

One reason Fujie left private practice for the judiciary was to show young Asian American and Pacific Islander women that they could do it too. She became a mentor, and for several years not only encouraged other lawyers to consider the bench but also assisted with their applications and mock interviews.

Fujie also promoted diverse candidates as a member of the late California Sen. Dianne Feinstein’s Judicial Advisory Committee for federal district court appointments. She now serves on Gov. Gavin Newsom’s Judicial Selection Advisory Committee for Los Angeles County.

“There are unbelievably qualified people of lots of diverse backgrounds for these judgeships,” says Fujie, who also sits on the ABA Board of Governors Commission on Governance. “But I think the problem, at least for [Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders], is recruiting, getting people to apply. If you don’t have people apply, you can’t appoint them.”

Challenging perceptions and addressing problems

Released in November, the 2023 ABA Profile of the Legal Profession reveals other minority groups continue to struggle with advancement to higher levels of the profession.

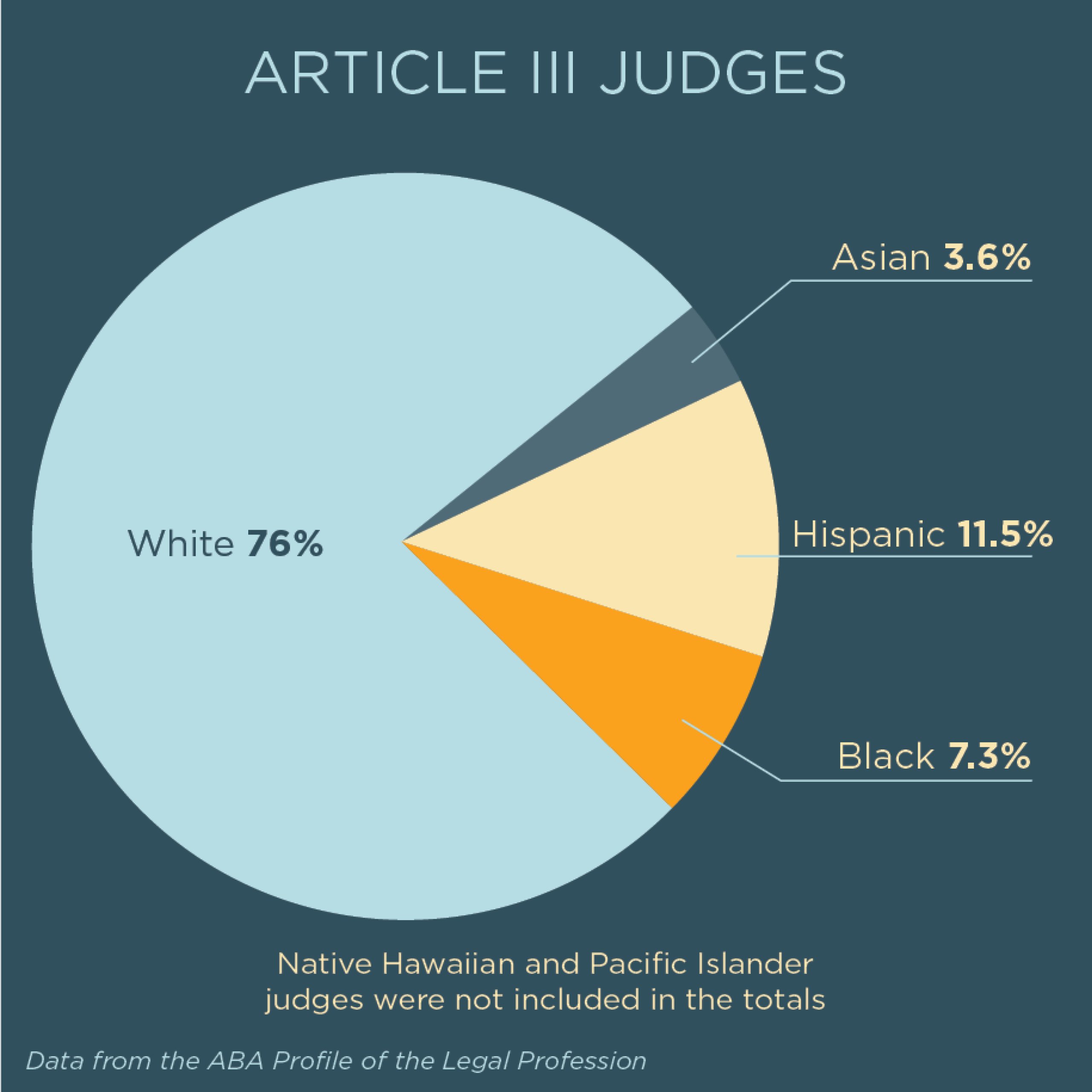

(Infographic by Sara Wadford/ABA Journal)

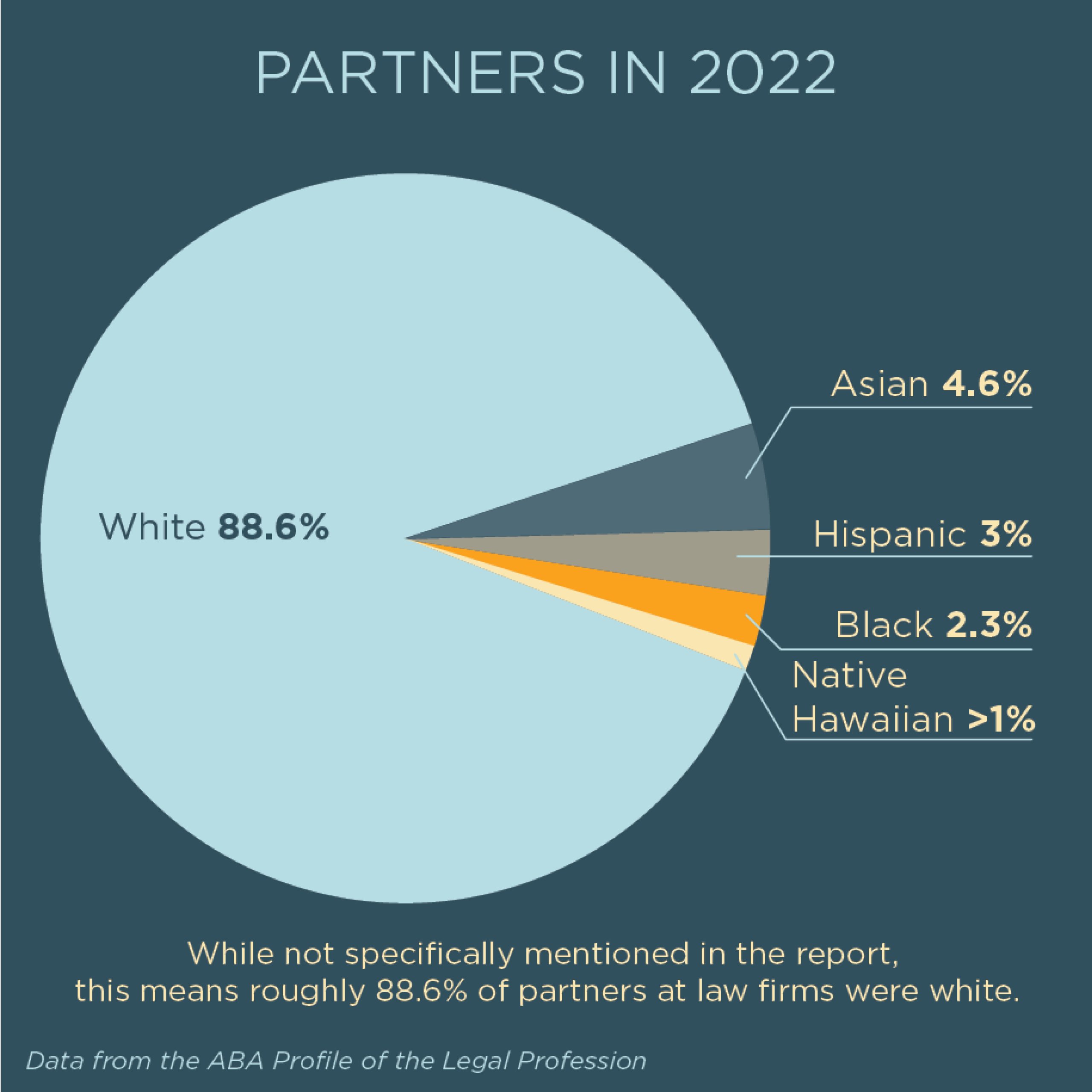

(Infographic by Sara Wadford/ABA Journal)According to the report, the number of diverse lawyers who make partner at U.S. law firms has slowly but steadily increased. In 2022, 11.4% of all partners were lawyers of color, compared with 2007, when 5.4% were lawyers of color. While not specifically mentioned in the report, this means roughly 88.6% of partners at law firms were white.

In 2022, Asian Americans comprised 4.6% of all partners, followed by Hispanic lawyers, who made up 3%, and Black lawyers, who made up 2.3%. The report also shows less than 1% of partners were Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander.

Like Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders, Hispanics are underrepresented among partners compared to their share of the U.S. population, which is 19.1%. Black partners are also underrepresented, as Black individuals comprise 13.6% of the population.

The ABA Profile of the Legal Profession also sheds more light on the diversity of the federal judiciary. There were 1,423 sitting Article III judges—which includes active and senior judges—as of October 2023.

Since this number includes senior judges, the legacy of exclusion is more strongly reflected in the proportions. Asian Americans made up 3.6% of those judges. Black and Hispanic judges, respectively, comprised 11.5% and 7.3%. White judges are 76% of sitting Article III judges. Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander judges were not included in the totals.

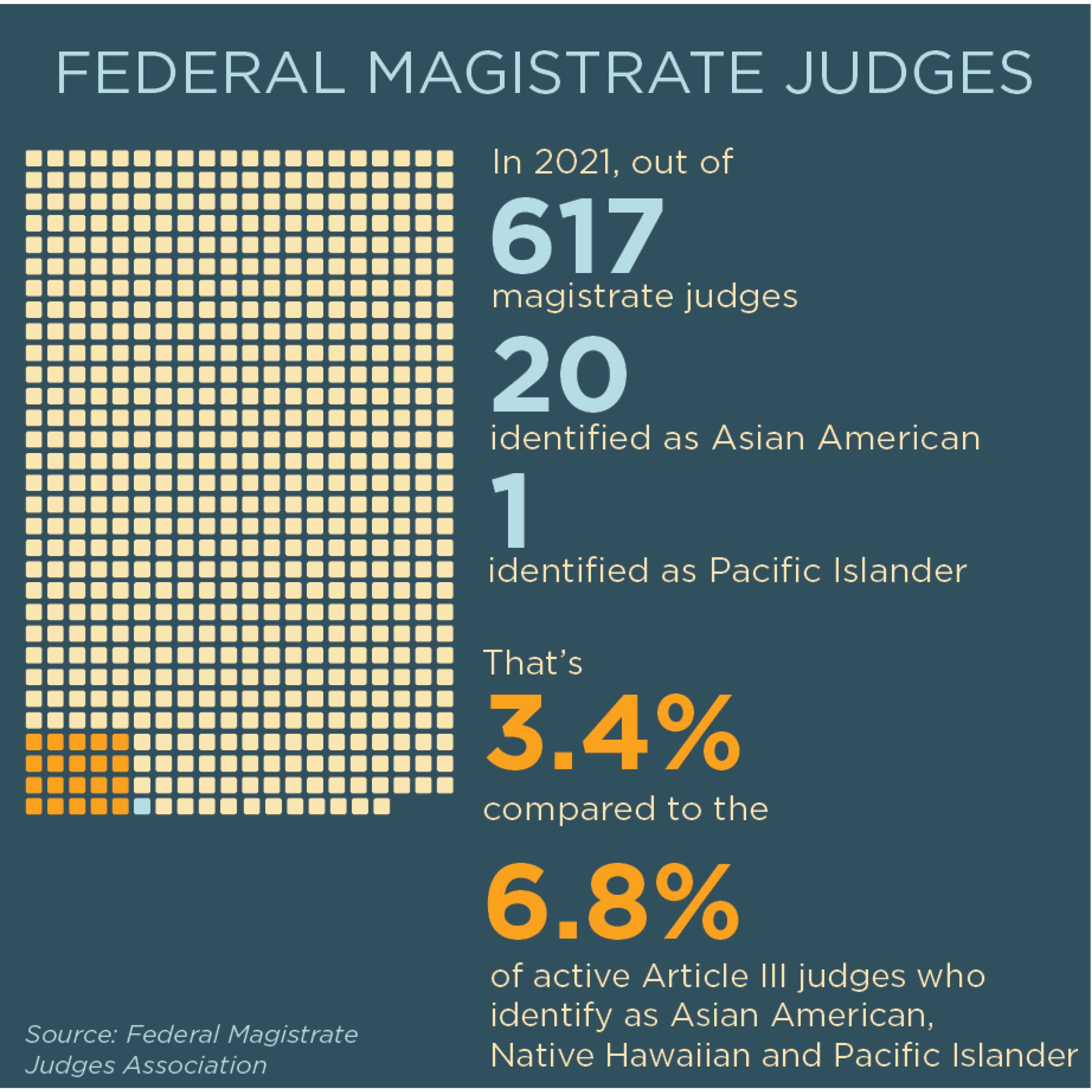

(Infographic by Sara Wadford/ABA Journal)

(Infographic by Sara Wadford/ABA Journal)“Every group faces different types of issues, but for Asian Americans, I think one of the main problems continues to be invisibility,” Liu says. “In the discussion of diversity, sometimes Asians count, and sometimes they don’t count. And Asian Americans have historically been a small group. But they’re not very small anymore, certainly not in the legal profession.”

In Mollway’s 2021 book, The First Fifteen: How Asian American Women Became Federal Judges, she shares her story and the stories of 14 other Asian American women who were appointed as Article III judges in the prior two decades.

Mollway highlights patterns in their stories, including that many needed outside validation before applying for judgeships. While they viewed themselves as good lawyers, she says they didn’t automatically consider the opportunity until talking with colleagues.

“People happened to ask me whether I was putting my name in, and I was surprised,” Mollway says of her experience. “You know, ‘Why are you asking me? Why would I do that?’ But it was very flattering that people even thought of me in that light.”

“It made me imagine whether it was something I was interested in,” adds Mollway, who was chief judge of the District of Hawaii from 2009-2015. She now serves as a senior judge.

Other judges point to additional factors that may hinder their peers’ progression to the bench.

Judge Rupa Goswami was born in India and grew up in Florida, where her parents managed hotels. She was the first in her family to become a lawyer and served as a federal prosecutor before being appointed to the Los Angeles County Superior Court in 2013.

The Asian American and Pacific Islander community is broad and complex, Judge Rupa Goswami of the Los Angeles County Superior Court says. (Photo courtesy of Judge Rupa Goswami)

The Asian American and Pacific Islander community is broad and complex, Judge Rupa Goswami of the Los Angeles County Superior Court says. (Photo courtesy of Judge Rupa Goswami)Goswami, who taught Asian American civil rights at Southwestern Law School, argues Asian Americans are overlooked in history classes and burdened by stereotypes that they are “geeky math people” who are better suited for medical and engineering careers. She adds that many Asian Americans who pursue law opt for corporate or intellectual property work over government or litigation positions, which are often a more direct path to the judiciary.

Like Fujie, Goswami is a member of Newsom’s Judicial Selection Advisory Committee for Los Angeles County. She previously served on the State Bar of California’s Commission on Judicial Nominees Evaluation and remembers finding feedback about Asian American women vying for judgeships troublesome. On several occasions, these women were described as “petite” or “adorable” or “so soft-spoken” that they could struggle to control a courtroom.

“I was happy to be in the room and to be able to say, ‘Well, maybe we should question the stereotypical inputs that these people are giving us,’” Goswami says. “Because maybe their perception of this person is also coming from some kind of implicit bias where they assume that Asian women are demure.”

Goswami, one of the first South Asian women on the bench in California, cites another crucial misconception. In her experience, many Americans only think about people who have Far East origins as Asian American, when in fact, many others—including those with Indian, Filipino and Malaysian roots—are members of this group.

“It’s a big community, and I think that’s part of the reason why it’s been hard to get Asian American representation,” Goswami says. “Even though we’re the fastest-growing U.S. racial group, we’re a wide diaspora in terms of language and backgrounds.”

(Photo courtesy of Justice Robert Torres Jr.)

(Photo courtesy of Justice Robert Torres Jr.)Supreme Court of Guam Justice Robert Torres Jr. also has felt misunderstood as a Pacific Islander, a group that includes people who trace their ancestry to Guam, Samoa or other Pacific islands. Torres, who graduated in 1980, had classmates at the University of Notre Dame who asked if he lived in a grass hut and knew how to drive. Others questioned whether he was a U.S. citizen and thought Guam was near Puerto Rico instead of in the western Pacific Ocean.

Even after joining the bench in 2004 and later becoming chief justice, Torres noticed some stateside colleagues were hesitant when he expressed interest in leadership in national judicial organizations. This includes when he vied to become president of the American Judges Association, a position he held from 2018 to 2019.

“When I tossed my hat into the ring, there was a little bit of apprehension about whether I could manage such a large organization,” he says. “But I wasn’t deterred, and I managed to get the support from people.

“That is one thing many AAPI individuals have—they’re motivated, and they work hard,” adds Torres, who is now a member of the ABA Judicial Division Appellate Judges Conference’s executive committee. “They can leverage that to their advantage to prove themselves, but it’s unfortunate it has to happen that way.”

Investing in the future

Many Asian American and Pacific Islander judges use their influence to support others in their community who aspire to the bench. They also look to the National Asian Pacific American Bar Association, as well as local affinity bar associations, which for years have helped identify and elevate judicial candidates.

Hawaii Supreme Court Justice Sabrina McKenna, who was born in Tokyo and became the first openly LGBTQ+ Asian American to serve on a state high court in 2011, is one of these judges.

(Infographic by Sara Wadford/ABA Journal)

(Infographic by Sara Wadford/ABA Journal)Along with recommending colleagues for state and federal court positions, she joins wider efforts to promote judicial diversity. According to the World Justice Project, one principle of the rule of law is accessible and impartial justice, which, she says, requires justice to be delivered by judges who reflect the makeup of their communities.

McKenna, who serves on the ABA Working Group on Building Public Trust in the American Justice System, has led a series of discussions on this topic, including during a trip to meet with lawyers and judges in India last fall.

“We have to stop talking about it like it’s an aspirational goal,” says McKenna. “It’s a requirement: We need to comply with the rule of law, which requires judicial diversity. We need to talk about it in that context.”

To this end, she credits the National Asian Pacific American Bar Association, which names as one of its goals enhancing the pipeline of credible Asian American and Pacific Islander nominees for the federal bench. McKenna says it has been quite effective, as a record 29 Asian Americans, Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders have been confirmed as Article III judges during President Joe Biden’s term.

In comparison, 13 were confirmed during President Donald Trump’s administration; 22 were confirmed during President Barack Obama’s administration.

“Our primary focus has been on the federal bench, and since the Obama years, NAPABA has had a lot of success,” says Purandare, its executive director, who is South Asian.

“We have worked very closely with members of the administration and senators on both sides of the aisle, ensuring that we keep those strong relationships to shepherd people through the process, from nomination through confirmation.”

Judge Benes Aldana was first the Asian Pacific American chief trial judge in U.S. military history. (Photo courtesy of Judge Benes Aldana)

Judge Benes Aldana was first the Asian Pacific American chief trial judge in U.S. military history. (Photo courtesy of Judge Benes Aldana)As a past president of the National Asian Pacific American Bar Association’s Judicial Council, retired Judge Benes Aldana has been part of initiatives to increase the number of federal Asian American and Pacific Islander judges. The organization also encourages its regional affiliates to engage in similar work in state courts, where he says more diverse judges are desperately needed.

“Having looked at different ways judges are trained around the world or prepared to take on the job, I think we do a poor job of preparing our judges,” says Aldana, who is Filipino American and the first Asian Pacific American chief trial judge in U.S. military history. “What I mean is, no one is trained to be a judge in law school.”

In 2019, Aldana, the president of the National Judicial College in Reno, Nevada, helped launch its Judicial Academy, which educates lawyers about the judiciary and aims to improve their chances of ascending the bench. As of January, Aldana says 25 of 106 alumni had become judges, and most were women or people of color.

Aldana—a longtime ABA member and current chair of the Commission on Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity—adds that several ABA initiatives introduce underrepresented law students to opportunities in the courtroom. Among these are the Judicial Intern Opportunity Program and Judicial Clerkship Program.

Other areas of concern

Diana Song Quiroga has served as a magistrate judge on the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of Texas since 2012. Magistrate judges are appointed by active district court judges to handle various judicial matters during eight-year terms, and Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders are even more underrepresented in their ranks.

(Photo courtesy of Judge Diana Song Quiroga)

(Photo courtesy of Judge Diana Song Quiroga)According to the Federal Magistrate Judges Association, 20 magistrate judges identified as Asian American, and one judge identified as Pacific Islander out of 617 total in 2021. That’s a 3.4% proportion compared with the 6.8% of active Article III judges who identify as Asian American, Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander.

Song Quiroga, who was born in Taiwan and raised in Buenos Aires, Argentina, moved to the United States when she was 16. She served as an assistant attorney general and an assistant U.S. attorney in Texas before becoming a magistrate judge.

As chair of the ABA Judicial Division’s Standing Committee on Diversity in the Judiciary, Song Quiroga is also involved in trying to expand the pipeline. This includes visiting with students of all ages who may have never met a judge—or a judge with her background.

She views this outreach as especially important because clerking for a judge changed her own trajectory.

(Infographic by Sara Wadford/ABA Journal)

(Infographic by Sara Wadford/ABA Journal)“When I was growing up, I didn’t think of myself as a trial attorney or as a public speaker,” Song Quiroga says. “The more we—judges and lawyers—get out there in the community and let students see us, the more they’ll see there is no prototype. They will see different faces, different personalities, people who grew up in cities and in rural areas and people who speak one language or many languages.”

At the state level

Just as the subset of federal magistrate judges contends with low representation, state courts experience varied success in terms of advancing Asian American and Pacific Islander candidates.

It’s difficult to get the full picture because not all states collect or report judicial demographics, but according to the 2023 ABA Profile of the Legal Profession, only 20% of state high court justices are people of color.

The ABA cites a May 2023 report from the Brennan Center for Justice, which reveals 10 of the 347 total state supreme court justices are Asian American. There are no Asian American justices in 42 states. And New Jersey and New York—two of the states with the largest Asian American populations per capita—do not have an Asian American justice.

Rahat Babar, the deputy executive director for policy at the National Asian Pacific American Bar Association, previously served as the first Bangladeshi American judge on the New Jersey Superior Court. He contends “the challenge is baked into the structure of our nation’s system of government” because with 50 states, there are 50 different ways of selecting judges.

Rahat Babar was the first Bangladeshi American judge on the New Jersey Superior Court. (Photo courtesy of Rahat Babar)

Rahat Babar was the first Bangladeshi American judge on the New Jersey Superior Court. (Photo courtesy of Rahat Babar)For example, Babar says, in New Jersey, the governor nominates and the state senate confirms judicial nominees. However, across the Delaware River in Pennsylvania, state trial court candidates must run in contested partisan elections.

“Regardless of the type of process, the appointment of judges remains—at its core—a political process, which requires a political strategy,” Babar says.

“Whether it’s voting for qualified judicial candidates that represent the diversity of our communities or supporting decision-makers that prioritize judicial appointments that reflect our diversity, the mission to broaden our state judiciaries fundamentally involves a holistic approach, and it starts with the local community itself.”

Unsurprisingly, Mollway has seen significant changes in the judiciary since she joined several decades ago. But like her colleagues, she wants more to be done and anticipates efforts to empower other Asian American and Pacific Islander judges to continue to increase.

“If you talk to people in our positions 20 years from now, they’ll have had such a different experience,” Mollway says. “These might all be temporary problems. I hope so.”

This story was originally published in the April-May 2024 issue of the ABA Journal under the headline: “Missing Benchmarks: Despite progress, Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders are still underrepresented in the judiciary.”

Sidebar

By the Numbers

Infographics by Sara Wadford