Lawyers involved in the gun debate are primed for the Supreme Court to take the next big case

Photo illustration by Brenan Sharp/ABA Journal

It was a Tuesday night in late August when Kyle Rittenhouse stood outside of a vehicle dealership on the dark streets of Kenosha, Wisconsin. The armed Illinois teenager was dressed in a baggy green T-shirt that hung over his blue jeans. He had crisscrossed the straps of his Smith & Wesson AR-15-style rifle and a “medical kit” across his chest.

“People are getting injured, and our job is to protect this business, and part of my job is to also help people,” the 17-year-old told the conservative news website the Daily Caller.

Kyle Rittenhouse Nineteenth Judicial Circuit Court via AP

The police shooting of Jacob Blake on Sunday, Aug. 23, sparked a wave of peaceful demonstrations but also rioting, arson and looting. It was the third night of protests. Rittenhouse was among a group of self-described militia members who said they were on the streets to protect demonstrators and property.

Rittenhouse was later involved in a violent confrontation that left two men dead and a third injured. Prosecutors say he first opened fire in a parking lot and shot and killed protester Joseph Rosenbaum, fracturing his pelvis, perforating his right lung and liver and grazing the right side of his forehead.

He was seen later running down a street with several protesters in pursuit. Rittenhouse fell to the ground, shooting Anthony Huber and Gaige Grosskreutz, who appeared to be holding a handgun, prosecutors say. Huber died from his wounds, and Grosskreutz was injured. Rittenhouse faces six charges, including first-degree intentional homicide, in connection with the shootings.

The scenes in Wisconsin illustrated a tension between the Second Amendment right to bear arms and the First Amendment right to peacefully protest. Moreover, they are a snapshot of the state of gun laws in America. Rittenhouse, 17, is too young to legally carry a firearm in the state. Indeed, prosecutors also charged him with underage possession of a dangerous weapon; however, under Wisconsin law, it is not illegal for adults to visibly carry firearms during protests.

Kyle Rittenhouse, left, carries his rifle through protests on Aug. 25 in Kenosha, Wisconsin, where two men were fatally shot. He was later arrested in connection with the shootings. Adam Rogan/Journal Times via AP

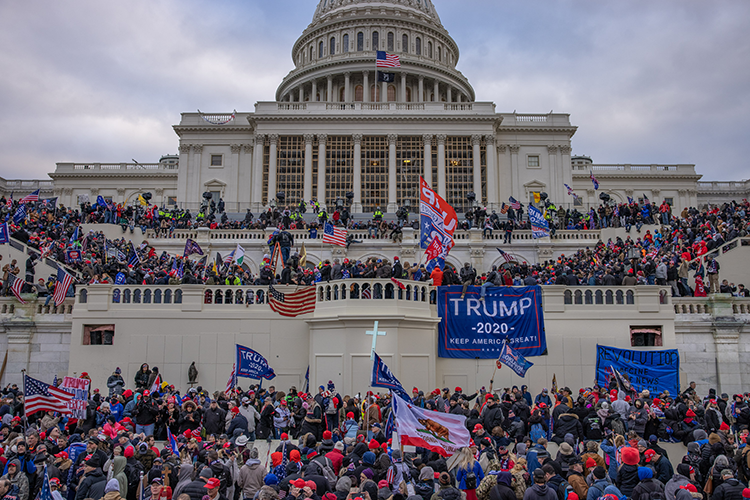

Armed protesters have appeared elsewhere. In April, hundreds of demonstrators descended on the Michigan State Capitol in Lansing in defiance of stay-at-home orders to flatten the curve of COVID-19.

Protesters against a COVID-19 stay-at-home order—some armed—tried to enter the Michigan State Capitol in April. rew Harnik/POOL/AFP via Getty Images

Masked militiamen wearing tactical vests and holding military-style weapons were among the protesters, unnerving lawmakers and prompting some to come to work that day in bulletproof vests.

The U.S. Supreme Court has yet to rule conclusively whether openly carrying a gun in public falls within the scope of the Second Amendment; however, eight circuits have split three ways on the issue. It’s a lingering question that has preoccupied lawyers on all sides of the gun debate, leaving them in a state of legal uncertainty.

This year, the Supreme Court sent strong signals that it could end the suspense—and failed to do so. Lawyers say it’s only a matter of time until the court finally tackles the matter.

First, the court took on New York State Rifle and Pistol Association Inc. v. City of New York, New York, but it dismissed the case as moot in April after city officials amended an ordinance that barred gun owners from transporting guns through the city to a second home or to shooting ranges outside of city bounds. Many observers expected the conservative bloc on the court would choose from one of the 10 gun cases on its docket. It didn’t happen. In June, the court declined to take on any of them.

The flag-draped casket of Justice Ruth Bader Gins-burg lies in repose in front of the Supreme Court building in September. Kowalsky/AFP via Getty Images;

Arnold & Porter attorney and gun control advocate Roberta Horton said the decision came as a surprise because only four votes are needed to grant certiorari. Those votes seemed to be among Justices Samuel Alito, Clarence Thomas, Brett Kavanaugh and Neil M. Gorsuch.

The confirmation of Amy Coney Barrett to the court in October has raised the stakes again. Speaking shortly after the death of Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Horton said Barrett was among the potential nominees who could expand gun rights. Barrett offered few clues on how she would rule in a gun case during her confirmation hearings, but as an appeals court judge, she dissented in a case upholding a ban on convicted felons possessing firearms.

As an appeals court judge, Justice Amy Coney Barrett dissented in a case upholding a ban on convicted felons possessing firearms. Tasos Katopodis/Getty Images

“I think there’s also a higher likelihood that one or more of the cases that raise issues of the reach of the Second Amendment are going to be heard,” Horton said.

Bob Levy is chairman of the board of directors at the Cato Institute, a libertarian think tank. He was co-counsel for Dick Anthony Heller in the landmark Second Amendment case District of Columbia v. Heller and bankrolled it. He says that after the New York gun case, some of the conservative justices suggested, “We’ve been played, and we know we’ve been played, but we’re not going to be played forever.

“There are going to be a lot of cases coming up through the circuits that are likely to raise these same issues, and at one time or another, they’re going to take one of those cases.”

10 years of silence

On June 26, 2008, attorney Alan Gura, the young gun rights lawyer arguing Heller, picked up the phone and dialed David Sigale’s number. It was a call that Sigale was waiting for.

The soft-spoken Chicago lawyer with a wide smile and shock of wavy brown hair had been preparing for this day. Now, it had finally come.

After ruling in favor of Otis McDonald, pictured after his 2010 Supreme Court victory, the justices were silent on the Second Amendment for 10 years. John Moore/Getty Images

Months earlier, Sigale had met Otis McDonald, the South Side gun owner who would become the lead plaintiff in a second landmark Supreme Court gun rights case, McDonald v. City of Chicago. At this moment, however, the attorney’s mind was on how the court would decide Heller.

Sigale knew if the court ruled against Heller, a wiry, gray-haired security guard fighting a Washington, D.C., law stopping him from possessing a handgun at home, all his work for McDonald would be for nothing. From May to June, he would sit at his computer each morning waiting for a ruling. Then, Gura’s call came.

“File it,” Gura said.

“It got filed 10 minutes later,” Sigale recalls.

Heller established a Second Amendment right to use a gun for self-defense in the home in the federal enclave of Washington, D.C., laying the groundwork for McDonald, which expanded that right to the states. Sigale remembers Otis McDonald as defying gun-toting stereotypes. The African American man in his 70s said he needed the gun for protection in his Morgan Park neighborhood. McDonald won, and the court struck down Chicago’s handgun ban.

Dick Anthony Heller, right, stands with attorney Robert A. Levy after oral arguments in his 2008 Supreme Court case. Photos by AP Photo/Pablo Martinez Monsivais

Heller and McDonald shocked gun control advocates, says professor Gregory Magarian of Washington University School of Law in St. Louis, even though the public supported expanding Second Amendment rights. Lawyers on the gun control side have been in a “state of legal stasis” since, he says.

“We’re still in limbo, where we know that there’s a Second Amendment right, but we don’t know what that Second Amendment right means,” Magarian says.

Gregory Magarian: “We’re still in limbo, where we know that there’s a Second Amendment right, but we don’t know what that Second Amendment right means.” Photo courtesy of Washington University School of Law

As fatal police shootings and gun violence ravage Black communities, and mass shootings and active shooter drills have become ingrained in the American experience, local and state governments have countered the threat by creating more gun laws.

As gun rights groups have fought those laws in the courts, it’s become a common refrain that trial judges are flouting the court’s ruling in Heller and undermining Second Amendment rights.

Some of the conservative justices on the court share that opinion. Justice Thomas called the Second Amendment a “constitutional orphan.” And when the court ended 10 years of silence after McDonald by taking on the New York gun case, Kavanaugh—who as a federal appeals court judge said D.C.’s ban on semi-automatic rifles and its gun registration requirement are unconstitutional under Heller—wrote in his concurrence that state and federal court judges “may not be properly applying Heller and McDonald.”

A 2018 study by Duke University School of Law professor Joseph Blocher and Eric Ruben, now a professor at Southern Methodist University’s Dedman School of Law, suggests that Heller has not been as consequential as gun control advocates feared. The study found that in 60% of nearly 1,000 gun cases through Feb. 1, 2016, the courts relied on Justice Antonin Scalia’s opinion in Heller when testing the limits of the Second Amendment. But the researchers also concluded that in Second Amendment claims fail more often than not. “If you focus in on public carry cases, and you focus in on cases where the parties are represented, and so it’s not pro se, and you focus on appellate decisions, you see a higher success rate,” Blocher says.

Public carry cases were among the 10 the court considered after the New York case. Lawsuits from Illinois and Massachusetts challenged bans on large-capacity magazines and military-style rifles. Another complaint opposed interstate handgun sales. In the San Francisco-based 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, there are several pending cases, including ones on background checks for purchasers of ammunition and restrictions on military-style rifles. In August, a three-judge panel overturned California’s ban on magazines that hold more than 10 rounds of ammunition.

In another closely watched open-carry case at the appeals court, Vietnam War veteran George Young challenged the denial of a permit to visibly carry a firearm. A trial court in Hawaii upheld the law, but the 9th Circuit overturned the ruling 2-1. The court heard the case en banc in September. At the time of writing, the court had not issued a decision. Young v. Hawaii could be the Supreme Court’s next big Second Amendment case.

Gun rights attorney David Jensen remembers the Wall Street Journal interviewing him after the 7th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals in Chicago ruled in the concealed carry case Moore v. Madigan.

“What I said was that the issue isn’t going to be resolved until the Supreme Court weighs in on it,” Jensen said. “That was 7 1/2 years ago.”

Two coalitions

Monte Frank, an attorney with Pullman & Comley and a member of the ABA House of Delegates, was living in Newtown, Connecticut, when Adam Lanza opened fire at the Sandy Hook Elementary School and killed 26 people, including 20 first-graders.

His daughter graduated from the school 18 months before the massacre. Lanza killed her third-grade teacher. “I saw firsthand the devastation that gun violence can bring to a community,” says Frank, who went on to represent Newtown against families who sued for negligence.

However, Sigale remembers listening on the phone as a woman told him how she had fled from her husband, a violent felon, who had been convicted of murder. She was living in public housing when a man attacked and raped her while her children were in the house. “The only thing that saved her was when her kid got the gun out of the safe and pointed and yelled,” Sigale says. The woman said in a 2018 lawsuit Sigale filed on her behalf that the East St. Louis Housing Authority threatened to evict her from her home if she kept a gun.

Covington & Burling lawyer Simon Frankel’s 12-year-old brother was visiting with their grandmother in Wyoming and was playing with another boy at a friend’s ranch. “One of them thought it would be fun to go get one of the parents’ guns. And they got the gun, and they thought it wasn’t loaded. But it was, and it went off, and my brother was killed.”

Whatever drives the attorneys involved in gun cases—a family tragedy, a desire to protect the vulnerable, curiosity in a new and evolving area of constitutional law—they are fighting cases that can be deeply divisive.

There is a perception that the gun lobby is louder. That could just be a function of how gun cases play out in the courts. After a series of devastating mass shootings, the perception is changing.

Kirkland & Ellis’ Paul Clement and Cooper & Kirk attorney David Thompson are among the most high-profile lawyers on the gun rights side. (Both declined requests for interviews.) They are often challenging local or state gun laws.

Kirkland & Ellis’ Paul Clement speaks at a press conference on behalf of his client, the New York State Rifle and Pistol Association, in December 2019. Drew Angerer/Getty Images

That means they will face local or state attorneys in court, says Joshu Harris, chair of the ABA’s Standing Committee on Gun Violence.

“With the gun litigation, you have a core group unified by relationships with organizations and industry. On the other side, it’s a looser coalition,” Harris says.

Amy Swearer, a legal fellow in the Meese Center for Legal and Judicial Studies at the Heritage Foundation, says gun control advocates, including former New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg and the group Brady: United Against Gun Violence, have been a part of the national conversation for years. She has noted a recent consolidation effort on the gun control side.

The Firearms Accountability Counsel Taskforce is part of the strategy to bolster the gun control movement. In 2016, shortly after the election of President Donald Trump, Brady, the Giffords Law Center to Prevent Gun Violence and the Brennan Center for Justice formed FACT by partnering with some of the country’s leading corporate law firms, including Paul Weiss, Rifkind, Wharton & Garrison; Covington & Burling; and Arnold & Porter. The coalition has litigated Second Amendment issues and looked for cracks in the Protection of Lawful Commerce in Arms Act, a law that shields gun manufacturers from liability for the actions of those who use their products. In 2005, President George W. Bush signed PLCAA into law after lobbying by the NRA.

Paul Weiss partner and FACT member H. Christopher Boehning says the legal landscape has shifted.

“It’s no longer the case where we have isolated gun prevention organizations that have modest financial support and thin staffs going up against the NRA or gun manufacturers and their hired lawyers,” Boehning says.

During the 2018 midterm election, gun control groups outspent the NRA, and gun control advocates are gaining as the NRA is in turmoil. New York Attorney General Letitia James sued to dissolve the NRA in August, accusing its leadership of looting the group to fund their lavish lifestyles. James said NRA CEO Wayne LaPierre used the group’s funds for extravagant trips to the Bahamas and to enrich friends and family members. Lawyers who represented the gun group have been fired, including Charles Cooper of Cooper & Kirk. Meanwhile, LaPierre batted off a leadership challenge that revealed bitter infighting. The NRA is still a powerful force in Washington. After the lawsuit was filed, Trump defended the group. “That’s a very terrible thing that just happened,” he said, suggesting the group leave New York and move to Texas.

Swearer expects to see more grassroots activism at the state and local levels and anticipates other groups will come to the fore. “It’s not just the NRA anymore,” Swearer says.

Space in the middle

Darin Scheer is a general commercial litigation attorney in rural Casper, Wyoming, where he lives on a small cattle farm with his wife. As a volunteer firefighter, he has responded to suicides and accidental shootings.

He is an ABA delegate for his state. At the 2020 midyear meeting in Austin, Texas, he objected to a resolution in favor of stricter rules for gun permits.

“I don’t think that the ABA should be in the business of recommending one-size-fits-all, top-down requirements for an issue like this that is constitutional,” Scheer said before the House passed the resolution.

What’s often lost in the decades-long fight over gun rights and laws is that Americans’ relationship to guns differs depending on where they live, Scheer says. He says people in his community do not buy guns just for self-defense. There is a tradition of fathers passing rifles down to their sons and teaching them how to hunt. Scheer says it sometimes appears to gun owners that constitutional rights are trampled because of the “irresponsible behavior of the few.”

“That irresponsible use leads to horrible tragedy. I’m not blind to that, and that’s wrenching. And I think anybody that ignores that side of the debate is being close-minded as well,” Scheer says.

Is there space in the middle to meet? J. Adam Skaggs, a special adviser to the ABA’s Standing Committee on Gun Violence and chief counsel and policy director at the Giffords Law Center to Prevent Gun Violence, says it is hard to find common ground when the gun rights side is pushing “an extremist agenda in the courts.” On the other hand, he says gun control advocates have much in common with Americans who support reasonable regulations.

“I think the central argument is that like all other rights, the Second Amendment is not unlimited and has always coexisted with strong regulations and laws,” Skaggs says. “That’s no different today than it was at any other point in history.”

Photo illustration by Brenan Sharp/ABA Journal

In 2019, the Pew Research Center found that 60% of Americans supported more restrictions, while 28% were happy with the status quo; only 11% thought the laws should be less strict. Regardless of party affiliation, majorities supported measures preventing people with mental illness from obtaining a gun, running background checks at gun shows and before private sales, prohibiting high-capacity magazines and banning military-style weapons.

Even Levy, who turned the tide for the gun rights movement when he won Heller, says the Second Amendment is not an “absolute right.” He would support background checks on the mentally ill and not object to bans of military-style weapons “based on lethality,” bans on magazines of 20 to 30 rounds, and some background checks.

“I don’t think any of this would be very effective, but I think that we ought to find out,” Levy says.

Mass shootings, “which as horrible as they are” are “insignificant in terms of the overall level of gun violence,” he adds. He blames the war on drugs for worsening gun violence within cities, calling it an “unmitigated disaster.”

“If you legalize drugs and get rid of that criminal incentive, I think you’d have a huge effect on inner-city gun violence,” Levy says.

Black Americans are 10 times more likely to be murdered with a firearm, according to the Giffords Law Center. More than half of gun homicide victims are Black men, even though they make up less than 7% of the population. In cities, gun violence often is concentrated in neighborhoods segregated by race. In Boston, according to the Giffords Law Center, 53% of gun violence happens in parts of the city that make up less than 3% of its streets and intersections. Blocher from Duke University School of Law says lawyers who are defending gun laws should also do more “to articulate the government’s interest in regulating guns,” and the wider impact on society.

He says that in constitutional cases, judges will ask what the government’s interest is and how a gun law can serve that interest. Blocher says that preventing deaths or injuries from gun violence is the “highest interest,” but it can be hard to produce tangible evidence that a gun law will save lives.

“If you think about the government interests a little more broadly or creatively, like preserving the sanctity of public spaces and people’s ability to learn and assemble peaceably and vote, or for that matter [allowing] legislators in Michigan to do their jobs without fear, then you can understand gun laws do a little more,” Blocher says. “They don’t just keep people safe. They keep them from being intimidated.”

This story was originally published in the Dec/Jan 2020-2021 issue of the ABA Journal under the headline: “Called to Arms: Lawyers involved in the gun debate are primed for the Supreme Court to take the next big case.”

Write a letter to the editor, share a story tip or update, or report an error.