Activists are fighting new voter suppression tactics in court

Illustration by Sara Wadford

Flashbacks to Russian interference in the 2016 election loom large over November’s presidential contest. But a threat more insidious than foreign meddling has long been operating within U.S. borders: voter suppression.

A study on the 2018 midterm elections by the Center for American Progress, a nonpartisan policy institute, reported “severe voter suppression” in states with highly competitive races, including Florida, Georgia, Texas and North Dakota.

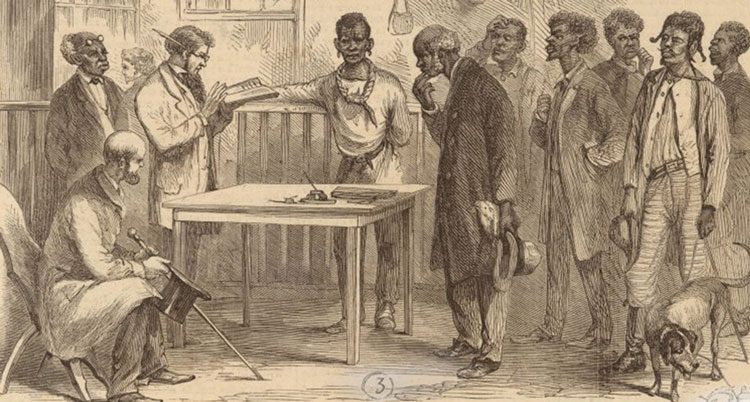

A 19th-century illustration of voter registration in Macon, Georgia. Photo courtesy of Art and Picture Collection, The New York Public Library.

This year marks two major milestones in United States voting history—the 150th anniversary of the passage of the 15th Amendment, which gave African Americans the right to vote, and the 50th anniversary of the Voting Rights Act Amendments of 1970, which abolished literacy tests and other methods of disenfranchising voters.

But despite these legislative achievements, it wasn’t long until end runs were made around voter protection laws, and those efforts are alive and well, election law attorneys and voting rights advocates say.

Today there are a variety of methods of suppression: onerous voter registration rules, voter purges, photo ID requirements, misinformation, harassment, poll closures, shortened voting hours and days, long lines and a perennial favorite—gerrymandering. Many modern practices, voting rights advocates say, are just creative ways of accomplishing the same goal.

“Wisconsin put voters in a coronavirus firing squad. Their choice was, ‘I can vote and die, or I can stay home and live,’” says Carol Anderson, chair of African American studies at Emory University. Photos by Stephen Nowland/Emory University Photo/Video.

“The tactics are the same as they were in 1865,” says the historian Carol Anderson, chair of African American studies at Emory University and author of the 2018 book One Person, No Vote: How Voter Suppression Is Destroying Our Democracy.

Taking away the vote

Poll taxes have long been illegal, but their specter cropped up in 2019, shortly after Florida passed Amendment 4 to its state constitution. The measure extended the vote to ex-felons, but the state soon tacked on a debilitating condition: Returning citizens would first have to pay any outstanding fines and fees, regardless of their financial ability to do so. Voting rights advocates branded the requirement a modern-day poll tax, and in February the Atlanta-based 11th Circuit unanimously agreed, finding the law unconstitutional, a determination affirmed by the trial court on remand.

Florida’s governor appealed and in July was granted an en banc rehearing by the 11th Circuit, which has become one of the most conservative appellate courts in the nation after judicial appointments by President Donald Trump. The Aug. 11 hearing date and uncertainty about how quickly the court will rule jeopardizes voting rights restoration for Florida’s returning citizens.

Purging voter rolls is another tried-and-true method of suppression. The method is less overt, with discriminatory purges often cloaked in an alleged need to “update.” The Brennan Center for Justice at New York University School of Law found that between 2016 and 2018, 17 million people were stripped of their status as registered voters.

Purges operate under the guise of fraud prevention, a purpose few would oppose were it true. However, Anderson contends claims of endemic fraud are “a lie perpetrated to justify voter suppression.” In the last decade, 25 states used the fear of voting fraud to enact laws that make it harder for people to vote.

This year, an unforeseen pandemic injected a potentially lethal dose of fear into the voting process and opened the door for another wave of voter suppression. COVID-19 has heightened the demand for mail-in voting, which advocates hope will increase participation, and which Republicans claim will increase voter fraud.

A line to vote in Milwaukee for Wisconsin’s spring primary election during the worldwide coronavirus pandemic was many blocks long. Photo by Sara Stathas for the Washington Post/Getty Images

Wisconsin became ground zero for post-COVID-19 voting rights when the state held its April primary, the final contested Democratic presidential primary of 2020. Mail-in voting offered protection from exposure, but thousands of Wisconsin voters did not receive absentee ballots before the deadline. Desperate legal and political maneuvers to extend the deadline, change the election date and suspend in-person voting all failed. At the 11th hour, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled against an extension for absentee voting, and thousands of Wisconsin voters braved long lines and the coronavirus to cast their ballots.

“Wisconsin put voters in a coronavirus firing squad,” Anderson says. “Their choice was, ‘I can vote and die, or I can stay home and live.’”

Democratic National Committee chairman Tom Perez, in an April interview on MSNBC’s PoliticsNation, called the Wisconsin debacle “voter suppression on steroids.”

In light of the pandemic, voting rights activists have called for states to hold all elections by mail, as do Colorado, Hawaii, Oregon, Utah and Washington. In those states, a ballot is automatically mailed to every registered voter at least two weeks before the voting deadline. In about two-thirds of the states, voters can request a mail-in ballot without providing any justification.

Voter fraud is a favorite Twitter topic for President Trump, who opposes mail-in voting even though he cast an absentee ballot in the Florida primary. On April 8, Trump tweeted that “Democrats are clamoring” for mail-in voting and claimed the practice “doesn’t work out well for Republicans.”

He went further in a pair of May 20 tweets. After Michigan Secretary of State Jocelyn Benson announced all 7.7 million Michigan voters would receive absentee ballot applications for both the August primary and the November general election, Trump tweeted that she was doing so “illegally” and threatened to halt federal funding to the state. Hours later, Trump threatened to “hold up funds” to Nevada, which had sent out absentee ballots for its June 9 primary election.

Legal challenges

Some voter suppression methods cut a wide swath, while others are leveled at specific minority groups.

A 2016 opinion by the Richmond, Virginia-based 4th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, North Carolina State Conference of the NAACP v. Patrick L. McCrory, invalidated a North Carolina law that required voters to show photo ID at the polls.

The judge said the law had been adopted with “discriminatory intent” and that its provisions “target African Americans with almost surgical precision.”

But the appeals court ruling didn’t put the matter to rest. North Carolina passed a voter ID law put on the ballot in 2018, and more lawsuits followed. In 2019 and 2020, federal and state courts issued preliminary injunctions blocking implementation of the law, which activists expect will remain in place through the November elections.

President Lyndon B. Johnson signs the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Photo courtesy Wikimedia Commons/Yoichi Okamoto

The most profound legal blow to voting rights in the modern era came seven years ago in the U.S. Supreme Court case Shelby County v. Holder, which Anderson says “gutted” the Voting Rights Act. She notes that two hours after the ruling came out, Texas implemented a strict voter ID law, and Alabama followed within a few months. “These legislators wrote the laws based on the types of identification that minority voters typically do not have,” she adds.

The Shelby ruling allows voting districts with documented track records of racial discrimination to change voting requirements without first obtaining approval from the Civil Rights Division of the U.S. Department of Justice (a policy known as preclearance) or petitioning the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia, as previously required under the act.

Voting rights advocates strongly condemn Shelby for eliminating oversight and disingenuously declaring racism a relic of the past. Since the court’s ruling, about half the states passed laws targeting minority voting rights.

“Where we are now has me seething and frustrated because none of this had to be,” says Anderson, who considers Shelby as wrongly decided as Plessy v. Ferguson. She says the 2013 opinion written by Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. “reshaped the legal and political landscape of America” in detrimental ways.

“The Justice Department has halted a lot of its voting rights enforcement and has been MIA in the area of elections and voter rights,” Vanita Gupta says. Photo by Sharon Farmer Photography.

Vanita Gupta, president and CEO of the Leadership Conference on Civil & Human Rights, says that during her tenure in the Obama administration, “We were dealing with the devastating blow of Shelby, but the tools we had were diminished significantly. The Civil Rights Division [of the DOJ] was trying to be on top of protecting voting rights around the country. The states enacted restrictive voter ID laws. We engaged in litigation to stop the tide of racially discriminatory policies enacted in the states. It was a very active docket.”

Today, she says, “The Justice Department has halted a lot of its voting rights enforcement and has been MIA in the area of elections and voter rights.” She points to a Supreme Court brief filed by the government in Husted v. A. Philip Randolph Institute. “The DOJ argued that it should be easier for states to purge registered voters from their rolls—reversing not only its long-standing legal interpretation, but also the position it had taken in the lower courts in that case.”

Rep. John Lewis, D-Ga., at a 2013 press conference outside the U.S. Supreme Court before the justices heard arguments in voting rights case Shelby County v. Holder.Photo by Douglas Graham/CQ Roll Call via Getty Images

But even in the wake of Shelby, there are some glimmers of hope for voting equality. The Voting Rights Advancement Act of 2019 passed the House in December and is pending before the Senate Judiciary Committee. It is not expected to go for a floor vote this year, but it may pass if Democrats regain control of the Senate in November. The bill would establish new criteria to fill the preclearance gap Shelby left in the Voting Rights Act.

U.S. Rep.Terri Sewell, D-Ala., speaking at a rally at the U.S. Capitol for the Voting Rights Advancement Act of 2019. Photo by Michael Brochstein/SOPA Images/LightRocket via Getty Images

Myrna Perez, director of the voting rights and elections program at the Brennan Center for Justice, testified before Congress in September 2019 on restoring the Voting Rights Act, calling it “the engine of voting equality in our nation.”

Targeting the margins

Marginalized and vulnerable populations can be stealth targets for voter suppression. Residency requirements have been a perpetually vexing issue for Native Americans because reservations typically do not have streets with numbered homes.

Above: Sharon Lewis, a member of the Pueblo of Acoma, breathes a sigh of relief after finally casting her ballot at the Acoma Tribal Center in Acoma, New Mexico. Lewis had to wait more than 45 minutes after one of the two voting machines at the polling place broke down. Right: Jacqueline De Leon is a member of the Isleta Pueblo and the ABA Standing Committee on Election Law. Photo by Rick Scibelli/Getty Images; Natasha Rigg; illustration by Sara Wadford

At its midyear meeting in February, the ABA House of Delegates passed two resolutions urging states to remove voting barriers for Native Americans and Alaska Natives. One recommended changes in residency requirements that would make it easier for voters without street addresses to use alternative forms of ID to register. The same month, North Dakota agreed to a binding consent decree ensuring Native Americans can vote without an ID that shows a residential address.

Jacqueline De Leon, who is a member of the Isleta Pueblo and the ABA Standing Committee on Election Law, says voting rights violations for Native Americans are underreported. A staff attorney for the Native American Rights Fund in Boulder, Colorado, she testified in February before the Committee on House Administration’s Subcommittee on Elections in a hearing on barriers facing Native American voters.

De Leon notes that Washington state has its own Native American voting rights act. It permits a tribe to designate one building per precinct that voters can use as a residential address. At that location, voters can register to vote and can pick up or drop off a ballot. The bill received bipartisan support, even from high-ranking Republican officials such as Washington’s secretary of state.

“It’s a good solution to break the logistical challenges” for those who do not have a post office in their community, she says. “The Native American vote can influence elections on the margin, especially when they’re close. So the [voter suppression] tactics are stronger there.”

Even the physical conditions of a polling place can be enough to give Native Americans the clear message that even if their vote is legally protected, it isn’t particularly welcome. De Leon recalls that a few years ago in South Dakota, a polling location in a largely Native American precinct was made from a “repurposed chicken coop.” Chicken feathers were scattered all over the floor, and there was no bathroom. “The voters felt disrespected,” she says.

Other situations can only be perceived as threatening, says De Leon, who has witnessed “poll workers staring at Native American voters while the sheriff is outside, visibly fingering his gun.”

Protecting the vote

Phoenix criminal defense attorney Adrian Fontes was similarly alarmed when he drove past a polling location in a largely Latino precinct on the day of Arizona’s March 2016 primary. Fontes saw what struck him as a thinly veiled attempt at voter suppression: a legion of steely-eyed police officers positioned at intervals throughout a line of voters that stretched block after block. Nearly five hours later, some of the same people were still in line.

“Not in my town,” he vowed to himself. “This is not America.”

Fontes, who resides in what he calls “the Trumpiest county in this country” had a busy law practice when he threw his hat in the ring for county recorder, the office that oversees elections in Maricopa County. To his shock—and just about everyone else’s—he won.

Photo of Adrian Fontes by Alonso Parra

Fontes enacted election policy reforms that vastly impacted Maricopa County, which, with nearly 4.5 million residents, is the fourth most populous county in the United States. In its 2018 elections, 40 “vote anywhere” centers—locations where any registered voter can cast a ballot, no matter where they live in the county—opened, and tens of thousands of previously denied voters were added to the rolls.

A study by political science professors at Dartmouth College and the University of Florida found that African Americans and Latinos in Florida who voted by mail were twice as likely to have their ballots rejected as white voters. Despite this fact, mail-in voting is gaining momentum.

But it’s not a panacea—absentee ballot measures have boosted voter participation in some states but not in others.

Court challenges are pending in Florida and other states where voters have to pay their own postage—including some mail-in ballots that require more than one 55-cent stamp. That may not seem unreasonable for the electorate at large, but it can be a bar for low-income voters or those who live in remote locations where stamps are not easily obtainable.

In California, Oregon and Washington, however, state election officials are legally required to include prepaid postage on ballots, and in April the American Civil Liberties Union filed a complaint on behalf of Black Voters Matter challenging Georgia’s refusal to provide prepaid postage for ballots.

Illustration by Sara Wadford

Georgia already faced allegations of voter suppression and mail-in irregularities after the 2018 gubernatorial election.

Attorney Stacey Abrams, a Democrat, narrowly lost her bid for the governor’s seat to Republican Brian Kemp, who by virtue of his then-position as Georgia’s secretary of state was in charge of overseeing the election. Calling Kemp an “architect of voter suppression,” Abrams lost the election by less than 55,000 votes (1.4 percentage points) and attributed it to the closure of polling locations in minority neighborhoods, rejection of absentee ballots and purging of voter rolls.

Stakes ramping up

Anderson foresees heightened attacks on voting rights in the November election. She expects some of it will be aimed at voting blocs that have not until recently been considered a threat. “College students are on today’s voter hit list, too,” she says.

Students tend to be liberal and favor the Democratic Party, according to a 2019 survey by the Institute of Politics at Harvard University’s Kennedy School of Government.

Results showed that 45% of college students ages 18-24 identified as Democrats, 29% as independents and 24% as Republicans.

Texas, New Hampshire, Wisconsin and North Carolina have been trailblazers in efforts to quash the student vote. Tactics have included requiring out-of-state students to have in-state drivers licenses to register, inconveniencing students by removing ballot locations from college campuses and gerrymandering.

Some states throw up significant obstacles to inhibit out-of-state college students from voting where they live for school, including arduous proof of residency requirements, a move activists call de facto gerrymandering.

A particularly egregious case of gerrymandering came to light in a 2019 redistricting that split the historically Black North Carolina A&T State University between two congressional districts, diluting the students’ voting power.

A September 2019 study by Tufts University showed a sharp spike in voter participation among students. The number of eligible students who cast ballots doubled in the last midterm elections (from 19% in 2014 to 40% in 2018).

So if campus engagement remains high, the student voting bloc may have a significant impact on the November elections. Its potential effect, and that of other voting groups on the radar, however, hangs in the balance with the success or failure of voter suppression efforts.

This story was originally published in the August-September 2020 issue of the ABA Journal under the headline: “Blocking the Vote: Activists are fighting new voter suppression tactics in court.”

Darlene Ricker, a legal affairs writer and book editor based in Lexington, Kentucky, is a former staff writer and editor for the Boston Globe and the Los Angeles Times.

Write a letter to the editor, share a story tip or update, or report an error.