Contemporary legal films shift away from lawyers as righteous heroes

Photo by Cinematerial.com

Like all forms of love, even the ones projected on screens eventually fade. What distinguishes American cinema from the same art form elsewhere has always been the proverbial, and even more predictable, happy ending. Americans have traditionally shown little interest in movies that end on a sad note. And they downright despise when a film fades to black, the final credits appear, and the audience is left not knowing how to feel.

Ambivalence is a positively unpatriotic, un-American impulse. In movies, we like to see narrative clarity: good triumphing over evil; heroes riding off into the sunset; and love affairs that, in Act I, seem mismatched, but by the final curtain, the guy gets the girl.

Movies about the legal system have their own familiar plotlines, but they, too, usually have satisfying resolutions—so unlike what happens in actual courtrooms. Hollywood, for instance, has always had a crush on crusading lawyers, unlike in novels, where lawyers are more often depicted as evil and duplicitous—with Dickens, Kafka and Dostoyevsky fine practitioners of that craft.

When it comes to movie heroes, the quintessential moral archetype has been Atticus Finch from To Kill a Mockingbird. But he is not alone. Cinema has offered a virtual parade of eloquent charmers, jury-seducers of the first order. To name a few examples, there’s Paul Biegler (Anatomy of a Murder), Frank Galvin (The Verdict), Henry Drummond (Inherit the Wind), Sir Wilfrid Robarts (Witness for the Prosecution), Sandy Stern (Presumed Innocent) and Kathryn Murphy (The Accused)—among scores of other smooth courtroom specialists—all with a God complex and a clear conscience.

THE LEGAL PLAYERS

Our all-time list of cinematic favorites

But judging from the films that have been released in this new millennium, the tropes that once dominated legal dramas have given way to an entirely new twist on the genre. Cinema has developed a newfound cynicism about the once-righteous trial attorney. Nowadays, perhaps consistent with our diminished faith in public institutions, the legal system and its practitioners, as depicted in movies, have been found wanting and guilty.

Think of it as the legal analog of fake news.

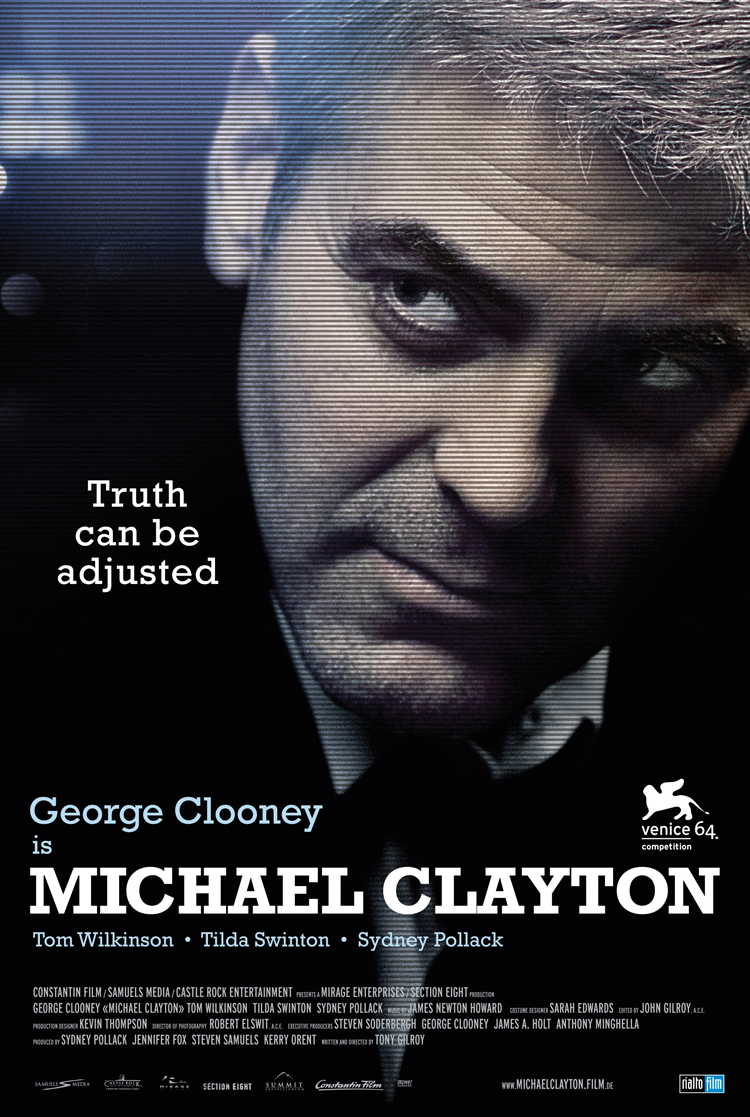

Here’s an autopsy of the moral attorney in this new age of perpetual injustice in the movies. For starters, we’re likely to see lawyers and law firms engaged in self-dealing, if not outright corruption, as in Changing Lanes and Michael Clayton. A lawyer is easily out-maneuvered by a cleverer defendant conducting his own defense, as in Fracture and Law Abiding Citizen. In Conviction, a man serving a life sentence has been so poorly served by his public defenders that justice hinges on his sister, a housewife and mother, to eventually attend law school and reopen the case on his behalf. Denial, set in the United Kingdom, is much more about a truth-seeking client than her generally remote solicitor and barrister.

Lawyers who possess real skill are shown representing seedy clients and holding court in the back seat of a Lincoln Town Car, which serves as an actual office in The Lincoln Lawyer. A quick-witted Chicago-based lawyer in The Judge returns to Indiana to both reconcile with and represent his father, a legendary trial judge charged with murder. But rather than serving as a hired gun who gallops into town to save the day, it’s the father—the accused judge—who is the moral center of the film, restoring balance to his estranged son’s lost life. Even Marshall, which involves a murder case handled by a young Thurgood Marshall, ends up being more of a buddy film with a hapless Jewish civil lawyer acting as lead counsel to Marshall’s second-chair sage. Loving is about an interracial couple whose true love affair expanded the constitutional right to privacy to include marriage. Their lawyers who took the case to the U.S. Supreme Court barely make a cameo appearance.

But perhaps the film that best represents how justice is cinematically revealed in this present moment is Spotlight, a movie that doesn’t prominently feature lawyers and is set in a newsroom, not a courtroom. Righteous investigative reporters from the Boston Globe are the protagonists in this true story. It is they who shine a spotlight exposing the pedophilic priest scandal in Boston. And it is their moral crusade that most successfully projected justice on a silver screen.

Of course, moviegoers are as fickle as film producers are sometimes feckless. We may one day see the return of the strutting cinematic figure of a lawyer bailing out his or her falsely accused client—projected once more like the lawyers we once loved.

Thane Rosenbaum is a novelist and distinguished fellow at New York University School of Law, where he directs the Forum on Law, Culture & Society, which hosts the annual FOLCS Film Series. He is a regular adviser and contributor on law as portrayed in popular culture for the

This article was published in the August 2018 ABA Journal magazine with the title “Cynicism in Cinema: Contemporary legal films shift away from lawyers as righteous heroes.”