Want to understand the logic behind a Supreme Court opinion? Focus on footnotes, says professor

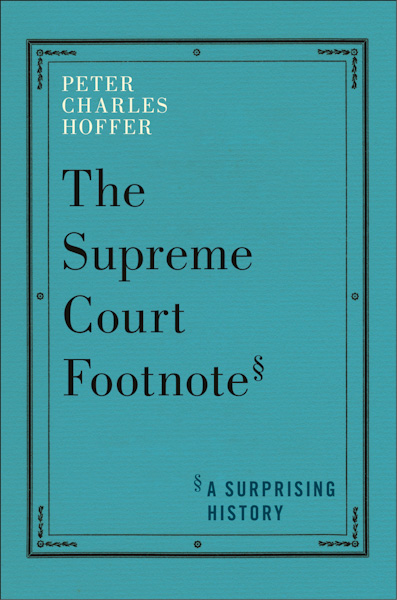

Numerous books have been written about the U.S. Supreme Court, including some by justices and former justices themselves. But a new book by Peter Charles Hoffer, a distinguished research professor at the University of Georgia, looks at historic rulings through a different lens in The Supreme Court Footnote: A Surprising History.

Hoffer examines eight notable Supreme Court decisions. Beginning with Chisholm v. Georgia, the 1793 opinion about state sovereign immunity, and ending with the controversial 2022 ruling in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, which featured more than 140 footnotes between the majority and the dissent, Hoffer details how the role of footnotes has grown significantly in becoming a way the court’s members speak to one another and to the public.

The book was recently published by NYU Press. Hoffer, who has authored more than 20 books, spoke to the ABA Journal about his newest work.

You devote the most time in the book to the Dobbs decision overturning Roe v. Wade. Why did footnotes play such a big role in that decision?

It’s remarkable that some of the justices think they are the historians. The way Justice [Samuel] Alito reasoned [in his majority opinion in Dobbs] and Justice [Antonin] Scalia in District of Columbia v. Heller [a 2008 ruling on gun rights] was they could look at historical materials and their judgment was sounder. It was Dobbs that got me to say it’s time to write a book about footnotes. Justice [Elena] Kagan really takes on the majority’s footnotes in her dissent in saying history and tradition don’t mean the same thing in 2022 as they did in 1868 or 1789. And that’s what her footnotes show. History continues and changes over time. You can’t say everything before Roe v. Wade was history and tradition or only look at a time when women could not vote.

You spotlight some enormous cases like Brown v. Board of Education and Dred Scott, but there are many—the Pentagon Papers case comes to mind—that did not make the book. What made you choose the cases that you did?

With Dred Scott, the footnotes show that the justices who agreed with [Chief Justice Roger] Taney are interested in the idea that slavery could go everywhere. And that language is what scared the free-state legislators. That’s what scared Lincoln, for example, and he made it a target of his presidential campaign. Muller v. Oregon [a 1908 14th Amendment case] introduced the friend of the court brief as a footnote. Brown brought in social psychology. Each one of the cases contributed something new, and the justices show their own understanding of history through the footnotes.

Did you have a favorite case in writing the book, or something you learned along the way, that might surprise readers?

The historian Stephen Ambrose had a quote, ‘My favorite book is the last one printed.’ For me, my favorite case is the one I’m going to write about next. The book was a revelation to me. I learned more about the justices than I could have imagined. I couldn’t pick one case in particular, but Dobbs definitely jumps out.

As your book comes out, the public’s confidence and job approval of the Supreme Court is at or near record lows, below any point in the last 50 years, according to recent news articles. What are your thoughts on that?

After Dred Scott, the approval rating of the Supreme Court in the north would have been at an all-time low. After Brown v. Board of Education, the court’s approval ratings in the South were historically low for a few years. So, approval ratings of the court go in cycles. The Supreme Court generally follows public opinion and is very aware of election results. But right now, a few of the conservative members are very surprised at how they’re being portrayed. I think they’ve misread public opinion. One hopes a moderate majority will emerge at some point.

Do you see footnotes continuing to be a way for justices to take down their opponents’ arguments and address broader issues?

As I write in the book’s conclusion, studying footnotes helps us understand the logic behind the opinions themselves. The notes in Heller and Dobbs, for instance, were directed by the justices at one another, continuing the dialogue begun in oral argument. The footnote, more than the opinion to which it is attached, opens the door to a conversation with the justice. It also gives the public a peek into the justices’ chambers to hear their thinking. The footnote also is addressed to the community of legal scholars and historians, opening a discussion inviting them to share and to comment.