The Supreme Court is in the building—contentious rulings behind, more major cases ahead

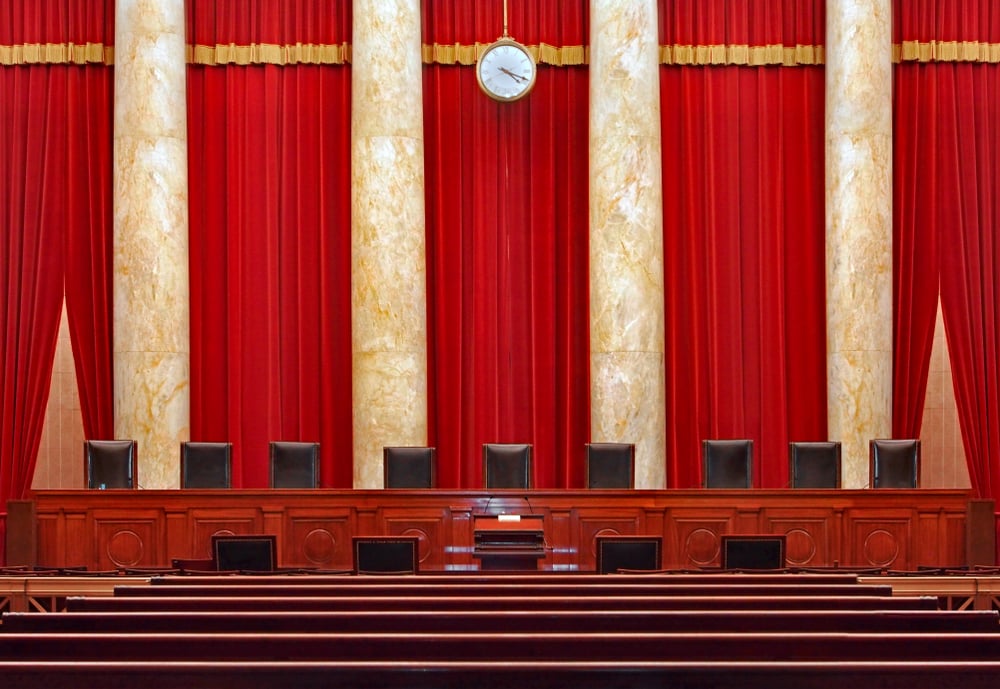

Image from Shutterstock.

U.S. Supreme Court justices are hanging up their phones after a year and a half of teleconference arguments because of the pandemic and returning to the bench for the new term that begins Monday. But the marble walls of their fortresslike building may do little to shield them from strong crosscurrents of criticism from politicians, reform-minded activists, and those dissatisfied with their recent emergency rulings on immigration policy, a federal eviction moratorium and the Texas abortion law.

“There’s no doubt that the court’s legitimacy is under threat right now, because the level of rhetoric and criticism of the court is higher than I can certainly remember at any point in my career,” said Kannon K. Shanmugam, a partner and Supreme Court specialist at Paul, Weiss, Rifkind, Wharton & Garrison, at the Federalist Society’s recent Supreme Court preview event.

The court building remains closed to the public—only the justices, arguing counsel, essential court personnel and a few reporters will be allowed to observe the arguments in the October, November and December sessions. But for the first time in its history, there will be a live feed of audio from the courtroom, allowing the public to listen to arguments in the same way it could when the court shifted to remote telephone arguments in May 2020 through all of last term.

The court will largely return to its free-for-all style of questioning but plans to hold at least one round of “seriatim” questions per side based on seniority. That is viewed by at least some court observers as a way of keeping Justice Clarence Thomas engaged in oral arguments as he was during the telephone sessions.

“It will be very interesting to see how that works in practice,” Paul D. Clement, a partner at Kirkland & Ellis who has argued more than 100 cases before the high court, said at the Heritage Foundation’s recent Supreme Court preview event. “My own sense is that this will be a little bit of a work in progress.”

Justices speak out about perceptions

The justices are embarking on a term with major cases on its regular docket about abortion, gun rights and religious liberty, among other issues. But the court has been much in the news since August with actions from its so-called shadow docket involving emergency applications for relief in three high-profile cases.

On Aug. 24, the court turned away a plea from President Joe Biden’s administration for relief from a federal district court order to reinstate the Trump-era “remain in Mexico” policy for migrants. On Aug. 26, the court blocked the enforcement of the pandemic-related federal moratorium on evictions.

And on Sept. 1, the court issued its much-debated opinion explaining its refusal to block a new Texas law that prohibits abortions once a fetal heartbeat is detected (usually about six weeks into a woman’s pregnancy) and authorizes private parties to sue to enforce the law against an abortion provider or someone who “aids or abets” an illicit abortion.

The Supreme Court’s popularity has taken a hit recently in public opinion polls. A Gallup poll conducted shortly after the court’s action in the Texas abortion case showed that just 40% of respondents approved of the job the justices are doing, down from 49% in July. A Marquette University Law School poll, also conducted after the Texas action, found that popular opinion of the court had declined to 49% from 60% in July.

Several justices have been speaking out since August against the idea that they are motivated by politics. Justice Stephen G. Breyer has been seemingly everywhere promoting his short book, The Authority of the Court and the Peril of Politics, which argues that the justices are not junior politicians in robes and that enlarging the court would be viewed as partisan and would threaten its authority.

Justice Amy Coney Barrett, at a Sept. 12 event at the McConnell Center at University of Louisville, said, “My goal today is to convince you that this court is not comprised of a bunch of partisan hacks.” (She was introduced by Sen. Mitch McConnell, R-Ky., who as Senate majority leader last year shepherded her nomination.)

Justice Thomas, speaking at the University of Notre Dame on Sept. 16, also sounded themes of nonpartisanship and said: “I think the media makes it sound as though you are just always going right to your personal preferences.”

Farah Peterson, a professor at the University of Chicago Law School, said at the school’s recent Virtual First Monday event that the recent speeches suggest the justices are “concerned that the court is starting to look partisan, and they want to reassure the public that there is a legitimacy to their decisions.”

But recent shadow docket decisions indicate that “we see … the Supreme Court charging ahead to make politically charged decisions,” she says.

Asking the court to overrule Roe

The cases on the court’s argument docket are not likely to help lower the temperature.

Most prominent is an abortion case from Mississippi that gives the justices an opportunity—long sought by abortion opponents—to overrule the landmark 1973 decision in Roe v. Wade, which established a constitutional right of a woman to terminate a pregnancy, and Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pennsylvania v. Casey, the 1992 decision that reaffirmed the basic holding of Roe and established the “undue burden” test for laws restricting abortion before fetal viability.

In Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, to be argued Dec. 1, the justices will review a 2018 Mississippi law that bars abortions after 15 weeks of pregnancy. Two lower courts held that the law is inconsistent with the Supreme Court’s abortion rulings.

In appealing to the high court in 2020, before the death of Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Mississippi asked whether all pre-viability restrictions on abortion are unconstitutional.

But in its July merits brief, the state went further and called for Roe and Casey to be overruled. “The conclusion that abortion is a constitutional right has no basis in text, structure, history or tradition,” the state said.

Jennifer Dalven, the director of the Reproductive Freedom Project of the American Civil Liberties Union, which has filed an amicus brief in support of the challengers to the law, said at the American Constitution Society’s recent Supreme Court preview that it is “pretty remarkable” that Mississippi is now seeking the broader outcome.

“The only thing that has changed is the composition of the court, and now they are asking for something different,” she says.

(The ABA also filed an amicus brief urging the court to uphold Roe v. Wade and its subsequent line of decisions.)

In New York State Rifle & Pistol Association v. Bruen, the court will weigh whether New York state’s denial of two individuals’ applications for permits for concealed carry of guns for self-defense violates their right to bear arms.

In the New York case, the two individuals have permits for gun possession for hunting and target practice but not the unrestricted licenses to carry weapons outside their homes, which requires a showing of “proper cause” of a need for self-defense.

The case may help resolve some of the questions left open by the court’s landmark 2008 District of Columbia v. Heller decision, which recognized an individual right to possess guns but said it was not casting doubt on laws forbidding the carrying of firearms in sensitive places such as schools or government buildings.

“This is the Second Amendment case that gun rights advocates have been waiting for,” Darrell A.H. Miller, a professor at Duke University School of Law, said at the ACS preview.

The case will be argued Nov. 3.

A ‘quirky’ religious-liberty case

The religious liberty case comes from Maine, which has a long-standing program in which the state pays for children from rural communities without their own public high schools to attend public or private schools elsewhere.

The state bars “sectarian” religious schools from participation, citing the First Amendment’s bar against government establishment of religion.

In Carson v. Makin, two families that seek to send their children to private religious schools at state expense are challenging the rule on First Amendment free exercise of religion and 14th Amendment equal protection grounds.

In its 2020 decision in Espinoza v. Montana Department of Revenue, the court held that religious schools could not be excluded from a program of tax credits for donations to private scholarship programs. That was based on the religious status of schools, while the Maine case will address religious use of state funding.

Thomas C. Berg, a professor and religious liberty scholar at the University of St. Thomas School of Law in St. Paul, Minnesota, says that while Maine’s “tuititioning” program is a quirky form of private school voucher, “this is an important case for a broader range of school choice-type programs” across the country.

The case is set for argument on Dec. 8.

With such divisive issues on the docket and others waiting in the wings, even longtime court watchers believe the justices are entering a potentially perilous period.

“I think we may have come to a turning point,” said Irving Gornstein, the executive director of the Georgetown Law Center’s Supreme Court Institute, at the school’s recent Supreme Court press preview. “It is all well and good for justices to tell the public that their decisions reflect their judicial philosophies, not their partisan affiliation. But if right-side judicial philosophies always produce results favored by Republicans, and left-side results always produce results favored by Democrats, there is little chance of persuading the public there is a difference between the two.”

Write a letter to the editor, share a story tip or update, or report an error.