Supreme Court will consider whether Andy Warhol’s Prince paintings violate copyright law

Vanity Fair’s November 1984 issue ran artist Andy Warhol’s illustration of musician Prince with a credit to photographer Lynn Goldsmith. Image from Goldsmith's brief.

A copyright case going before the U.S. Supreme Court on Oct. 12 encompasses the avant-garde pop art of Andy Warhol, the musical genius and personal vulnerability of the performer Prince and the rarefied worlds of rock photography and glossy magazines.

At stake is nothing less than the future of all “artistic expression,” says one side, while the other says the legal test proposed by its adversary “would transform copyright law into all copying, no right,” and turn the fair use defense under copyright into “a license to steal.”

“I think this is a potentially significant case for the whole creative realm, not just visual art,” says Roman Martinez, a Latham & Watkins partner who represents the New York City-based foundation charged with preserving the legacy of Warhol, who died in 1987.

Capturing ‘a vulnerable human being’

The case is The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts Inc. v. Goldsmith. The story begins with the respondent, Lynn Goldsmith, an accomplished rock photographer who had snapped iconic portraits of musical artists including Bob Dylan, Patti Smith, Bruce Springsteen and Mick Jagger.

In 1981, she approached Newsweek magazine with the idea of photographing Prince, who was just emerging as a rock icon. Goldsmith shot him in concert but also in her studio, where she gave him purple eyeshadow and lip gloss to accentuate his sensuality and set the lighting to highlight his chiseled bone structure. Her intention was to capture a “vulnerable human being,” she has said.

In 1984, when Prince shot to stardom with his “Purple Rain” movie and album, Vanity Fair magazine licensed one of Goldsmith’s photos from the 1981 shoot—for $400—to be used as an “artist’s reference” for a portrait it commissioned for a story on the rock star. The artist to whom Vanity Fair provided the photograph was Warhol, who was not without his own vulnerabilities but was famous for his paintings of Campbell’s soup cans and silkscreens of public figures, including Marilyn Monroe, that were often based on a photograph or newspaper image.

Warhol cropped Goldsmith’s photo and made other alterations before creating 12 silkscreen paintings and four other works that would become known as the “Prince Series.” Vanity Fair published one of them with its profile of Prince.

“Warhol’s portraits of Prince are materially distinct in their meaning and message,” Thomas Crow, a professor of modern art at New York University’s Institute of Fine Arts, wrote in an expert report on behalf of the Warhol Foundation. “Unlike Goldsmith’s focus on the individual subject’s unique human identity, … Warhol’s portraits … sought to use the flattened, cropped, exotically colored and unnatural depiction of Prince’s disembodied head to communicate a message about the impact of celebrity and defining the contemporary conditions of life.”

When Prince died of an accidental drug overdose in 2016, Vanity Fair’s parent, Condé Nast, published a commemorative magazine called “The Genius of Prince,” which used another of Warhol’s series on the cover, one known as “Orange Prince.” (The 1984 Vanity Fair article had used “Purple Prince.”)

Goldsmith noticed the image and realized it was based on her 1981 photo of Prince that had been licensed to Vanity Fair as an artist’s reference and complained to the Warhol Foundation. (She has claimed that she was unaware that her 1981 photo had been the basis for Warhol’s Prince Series.)

“What I rarely forget in my pictures is somebody’s eyes, and I kept seeing that image come up on various social networks, the quote-unquote Warhol, in different colors,” Goldsmith said in a deposition. “I went and looked at my digital archive and went, those are the eyes.”

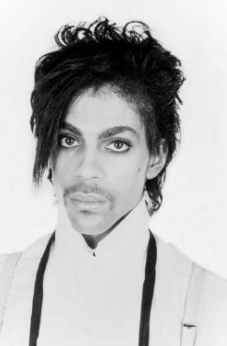

Lynn Goldsmith took this photo of Prince, which is the subject of a Supreme Court copyright case. Image from Goldsmith’s brief.

Lynn Goldsmith took this photo of Prince, which is the subject of a Supreme Court copyright case. Image from Goldsmith’s brief.

Judges unsuited as art critics?

After Goldsmith complained about the use of her image, the Warhol Foundation filed a pre-emptive lawsuit, seeking a declaratory judgment that the entire Prince Series was fair use under copyright law. The foundation argued that Warhol’s works were transformative because they conveyed a different “meaning or message” than the original work. Their suit said Goldsmith was trying to “shake down” the foundation.

The foundation doesn’t use that language in its Supreme Court filings but does say Goldsmith threatened to sue if she did not receive a “substantial sum of money.” Goldsmith ended up countersuing for copyright infringement and sought remedies that included blocking the foundation from selling, displaying or publishing the Prince Series. (The foundation retains the copyright for the series, though some of the 16 works are privately owned. One of the Prince Series sold for $174,000 in 2015, a relative bargain for Warhol works.)

Goldsmith’s court papers take issue with the idea that she sought a substantial sum, pointing to a 2016 communication with the foundation that said she sought to “find a way to amicably resolve” the dispute.

A federal district court awarded summary judgment to the Andy Warhol Foundation, holding that the Prince Series was fair use. The judge said Warhol had turned a “realistic photograph” of Prince as a “vulnerable, uncomfortable person” into a depiction of “an iconic, larger-than-life figure.”

A panel of the 2nd U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals reversed with a decision that said courts evaluating a follow-on work should not seek to determine the meaning or message of that work.

“The district judge should not assume the role of art critic and seek to ascertain the intent behind or meaning of the works at issue,” the panel said. “Judges are typically unsuited to make aesthetic judgments and … such perceptions are inherently subjective.”

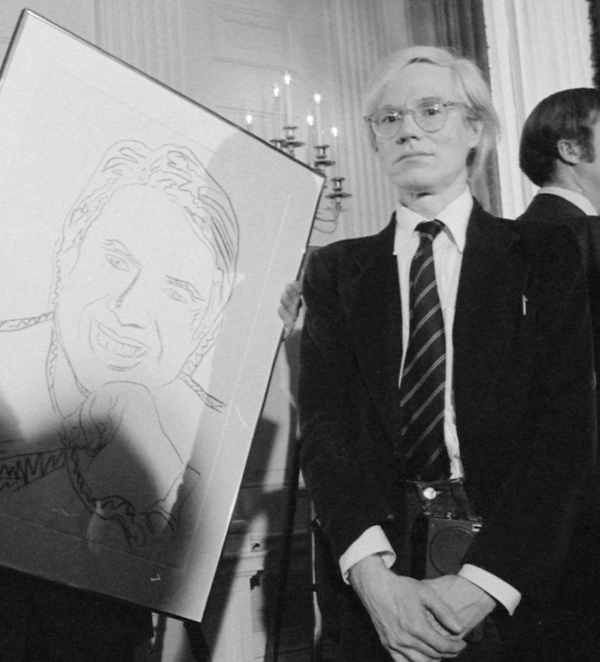

Andy Warhol in June 1977. Photo by the National Archives and Records Administration, CC-PD-Mark, via Wikimedia Commons.

Andy Warhol in June 1977. Photo by the National Archives and Records Administration, CC-PD-Mark, via Wikimedia Commons.

Reverberations in the art world

The 2nd Circuit’s views on that and other fair use has alarmed many in the art world.

“We think that making it harder for follow-on artists to borrow works in circumstances where they are really creating new art and adding meaning or message that is different from the original, we think that is extremely important to incentivize and protect artists to do that,” Martinez says. “It’s not just Warhol. Artists forever have been borrowing elements of each other’s work, especially certain artistic movements in the late 20th Century.”

Museums, including the Art Institute of Chicago and New York City’s Metropolitan Museum of Art and Museum of Modern Art, filed an amicus in support of neither party but which expresses concern about the 2nd Circuit’s decision.

“Under the Second Circuit’s ruling the status of museums’ display of original artworks that incorporate preexisting works is unclear,” says the brief.

Rebecca Tushnet, a professor at Harvard Law School and expert on copyright, says that “if the meaning of artistic works were objective, an art appreciation class would be like a standard math class: It would have only right and wrong answers.”

But art reflects “that different audiences come to works with different expectations and thoughts that make them see things differently,” says Tushnet, who joined an amicus brief by copyright professors in support of the Warhol Foundation.

Goldsmith, represented by Lisa S. Blatt of Williams & Connolly, says in briefs that the Warhol Foundation’s “reports of the death of art are greatly exaggerated.”

Warhol’s Prince Series was not transformative, and the foundation’s test for a key factor in the fair-use test would “devastate” derivate-work rights, such as for book-to-movie adaptations, the photographer argues.

Goldsmith has support from fellow photographers, the music industry, book publishers and even Dr. Seuss Enterprises L.P., which says in an amicus that it has “a vital interest in ensuring that the fair use doctrine is not improperly expanded to steamroll the legitimate rights of copyright owners.”

Peter S. Menell, who teaches intellectual property law at the University of California, Berkeley, says that Warhol was a known quantity when Congress passed the Copyright Act of 1976, but lawmakers did not mean to protect as fair use the kind of derivative works he was producing.

“In the last 10 to 15 years, we have really seen a growth of this kind of appropriation field of art, and it’s really driven by technology,” says Menell, who joined an amicus in support of Goldsmith.

There seems little doubt a decision in the case holds broad implications for copyright. But it may turn the Supreme Court, at least temporarily, into a panel of art critics.

While Prince’s reputation emerges unscathed in the case, Goldsmith’s court filings take some shots at Warhol, even as they laud his “artistic innovations.”

“Warhol’s celebrity portraits from the 1960s gave way to commissions for wealthy socialites” by the 1980s, Goldsmith’s merits brief says, also quoting from the Warhol Foundation’s own expert that “Warhol’s cutting-edge reputation had taken a beating by 1984.”

Martinez counters, in a reply brief, that Warhol was “universally recognized as a creative genius who pioneered the 20th century pop art movement” and the court “should reject any approach that dismisses quintessential works by Warhol—an innovator who blazed new trails for modern art—as contributing nothing in the eyes of copyright law.”

See also:

ABAJournal.com: “Supreme Court will hear photographer’s copyright dispute over Andy Warhol’s Prince portraits”

ABAJournal.com: “Fair Game: Does the fair use doctrine apply to Andy Warhol’s pop art?”

Write a letter to the editor, share a story tip or update, or report an error.