Supreme Court takes a byte out of computer crime law

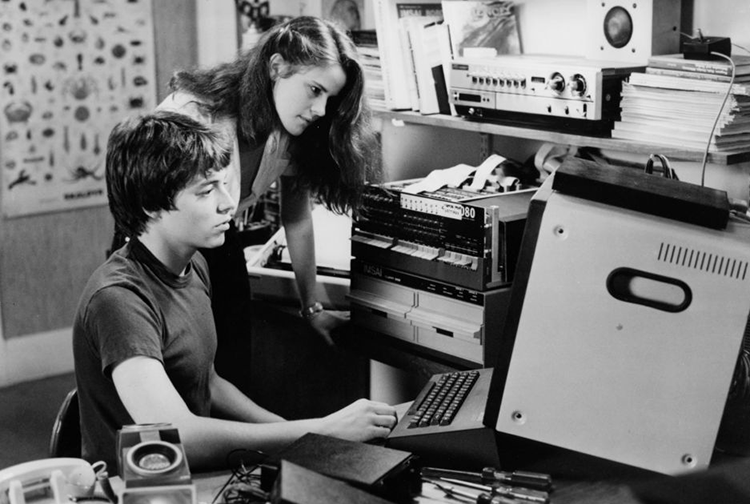

Matthew Broderick and Ally Sheedy starred in the 1983 movie WarGames. A key scene in the movie was cited in an amicus brief for Van Buren v. United States. Photo from Hulton Archive/Getty Images.

A U.S. Supreme Court decision handed down earlier this month has flown a bit below radar compared with the term’s bigger cases, but it is one that might be of interest to anyone who has ever bent the truth on a dating website or on social media, shopped or checked sports scores on a work computer, or happens to be a fan of the 1983 movie WarGames.

In Van Buren v. United States, the court ruled 6-3 to narrow the scope of a federal statute that makes it a crime to access a computer without authorization. The decision came in the case of a Georgia police officer who had run a license-plate search on his department’s computer system in exchange for money.

The majority held that the statute, the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act of 1986, covers individuals who obtain information from files, folders, or databases to which they do not have authorized access, but it does not cover those like the officer, Nathan Van Buren, who had authorized access but had improper motives for using it.

Justice Amy Coney Barrett wrote for the majority that “the government’s interpretation of the statute would attach criminal penalties to a breathtaking amount of commonplace computer activity.”

Under the government’s reading of the law, any employee who used a work computer for personal tasks when the employer limited computer use to business purposes would potentially violate the law, Barrett said. The same would go for those who violated the terms of service on a website or app.

Thus, the government’s interpretation would “criminalize everything from embellishing an online-dating profile to using a pseudonym on Facebook,” Barrett said.

Her opinion, which turned on an interpretation of the word “so” in the statute’s phrase “so entitled to obtain,” was joined by Justices Stephen G. Breyer, Sonia Sotomayor, Elena Kagan, Neil M. Gorsuch and Brett M. Kavanaugh.

Justice Clarence Thomas, in a dissent joined by Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. and Justice Samuel A. Alito Jr., said Van Buren had no right to use his authorized access to the police database to obtain information on the license plate for an improper purpose.

“Both the common law and statutory law have long punished those who exceed the scope of consent when using property that belongs to others,” Thomas wrote. “A valet, for example, may take possession of a person’s car to park it, but he cannot take it for a joyride.”

Thomas noted that violations of the CFAA typically lead to misdemeanor charges and that much of the federal code criminalizes common activity, citing laws that penalize a person who removes sand from the National Mall in Washington, breaks a lamp in a government building, or permits a horse to eat grass on federal land.

(Van Buren was convicted of a felony violation of the CFAA and sentenced to 18 months in prison for conducting the license-plate search in exchange for $5,000 in what turned out to be an undercover operation. That conviction is now overturned.)

A trip to the cinema to underscore changes in technology

Orin S. Kerr, a law professor at the University of California at Berkeley and a leading scholar on criminal procedure and computer crime law, says the Van Buren decision was a victory for those who favor the narrower reading of the CFAA.

“It doesn’t answer everything,” he says. “But it answers a lot.”

The court adopted a “gates up or down” inquiry for the law, Kerr says, meaning that “to violate the CFAA, a person needs to bypass a gate that is down that the person isn’t supposed to bypass.”

As Barrett put it, a person needs to “obtain information from particular areas in the computer—such as files, folders, or databases—to which their computer access does not extend” to have violated the statute.

Barrett cited Kerr’s work five times in her opinion, though she ultimately did not address whether the gate-based test should be based on technological or computer code-based limits, as Kerr had urged in an amicus brief, or whether the test should also take into account contract-based limits on computer access.

When Congress began considering the first federal computer crime statute in 1983, outside hackers were a key concern, such as the teenagers who were intruding into corporate and government computer systems for innocuous or nefarious reasons.

In his amicus brief, Kerr reminded the justices of a piece of popular culture that epitomizes the era.

“If you have a few minutes, watch how Matthew Broderick’s character logs in to Dr. Falken’s computer in the 1983 movie WarGames,” Kerr wrote. He even recommended a YouTube clip of the specific scene.

“Broderick dials up the computer and tries to gain access,” Kerr wrote in the brief. “A password prompt blocks him. He eventually guesses the correct password—‘Joshua,’ the name of Dr. Falken’s son—and hits enter. A flurry of data appears on the screen. The password prompt is replaced by a new prompt, ‘GREETINGS DOCTOR FALKEN.’ Broderick declares, ‘We’re in!’ He is then free to use the computer. … The moment of access is obvious, and the temporal line between initial access and post-access use is clear.”

Kerr pointed out that technological developments since the 1980s have muddled that line.

“To be sure, there are still moments like entering Doctor Falken’s computer with a password,” Kerr continued. “But in a hyper-connected world, our interactions with computers no longer fit the binary world of pre-access and post-access with a clear line between them.”

Today’s smartphones, laptops and other devices are almost constantly connected, Kerr says, and the idea of a computer as a single box with hardware inside has been transformed by cloud-based computing.

Insider access as a threat to computer security

The federal government argued in the Van Buren case that even in those first congressional deliberations in 1983 and 1984, lawmakers recognized that while outside hackers were getting the media attention, “the greatest threat to computerized resources remains personnel who are authorized to access them,” as a 1984 House committee report put it.

The U.S. solicitor general’s office, in its arguments in the case, had resisted the idea that its reading of the statute would cover situations such as inflating one’s height on a dating website or violating the terms of service of Zoom or eBay.

Megan Iorio, the counsel of the Electronic Privacy information Center, agreed with the government’s view on that question.

“Computer use policies have nothing to do with protecting the information on that computer,” says Iorio, whose Washington-based organization filed an amicus brief in support of the federal government. “And [companies’] business-use-only policies for computers, that’s not an access issue.”

She says Barrett’s opinion did not offer much guidance to lower courts on what defines authorized use. “That’s the head scratcher,” Iorio says.

Kerr argues that the Thomas’s point in dissent that a fair amount of seemingly innocuous activity is criminalized under federal law was not very convincing.

“Justice Thomas’s argument didn’t work for two reasons,” says Kerr. “First, most people access hundreds of computers every day. If a large proportion of those accessed are unlawful, then most Americans might commit dozens of crimes every day. That’s pretty different from some of the quirky crimes he mentioned, like permitting a horse to eat grass on federal land—which is not a serious problem for those of us who don’t regularly ride horses on federal land.”

Second, Thomas ignored the fact that felony liability is easily triggered under the CFAA, and “under his reading, violating terms of service with intent to profit, or in furtherance of any state tort, would be a felony,” Kerr says.

Both Iorio and Kerr agreed that lower courts will soon have opportunities to apply the Van Buren decision, including in an important case about unauthorized data scraping by computer “bots” that the high court remanded to a federal appeals court for reconsideration under the new ruling.

Advances such as data scraping, cloud computing, online shopping and dating and Facebook are a long way from the technology featured in WarGames.

Kerr notes that he first published an article about the question presented in the Van Buren case in 2003.

“That feels like a long time ago, but not much has changed since then,” he says. “The technology evolves, but usually it evolves pretty slowly.”

Write a letter to the editor, share a story tip or update, or report an error.