Solicitors general, past and present, reflect on ups and downs of job and arguing before SCOTUS

At the ABA 2024 Litigation Section Annual Conference in Washington, D.C., on May 2, three full-fledged holders of the solicitor general post and two former acting solicitors general engaged in a lively 90-minute session titled “May It Please the Court.” (Image from Shutterstock)

It isn’t often that a bipartisan group of U.S. solicitors general gather in public to discuss their unique role in the legal system and even gripe a little about the U.S. Supreme Court.

But that’s what happened recently in a packed hotel ballroom before the ABA 2024 Litigation Section Annual Conference in Washington, D.C., on May 2. Three full-fledged holders of the post and two former acting solicitors general engaged in a lively 90-minute session titled “May It Please the Court.” They covered the challenges of representing the federal government before the high court, their favorite and least favorite things about the job, their concerns over the rise of the court’s emergency docket and the growing length of oral arguments.

“I love the new format,” U.S. Solicitor General Elizabeth B. Prelogar said about the court’s addition of a seriatim round of questioning after their traditional “free-for-all round.” The extra round, with the justices going in seniority order but not being interrupted by their colleagues, has sometimes doubled the normal hour prescribed for argument.

Prelogar, a former career line assistant in the office, has been solicitor general since early in President Joe Biden’s administration. She noted that the seriatim round, which she and some of the former officeholders call the “round-robin round,” allows the justices not only to ask more questions of the lawyers but also to continue the conversation among themselves about the case before them.

“A lot of time at argument is spent with the justices putting some of their cards on the table, and I think the new format means both of those conversations can happen in an orderly fashion,” Prelogar said.

Two former acting solicitors general under former President Barack Obama, Neal K. Katyal and Ian H. Gershengorn, also expressed support for the expanded arguments. But two former SGs who served under Republican administrations were less enthusiastic. (All four of the former officeholders now regularly argue in the court as private practitioners.)

“I think I personally liked the 30 minutes [per side] and you’re done format better, just because it was a little bit less painful,” said Noel J. Francisco, who was solicitor general for most of former President Donald Trump’s administration.

Paul D. Clement, who served in the job under former President George W. Bush, has argued multiple times under the new format, as have the other “formers” on the panel.

“I’ll just put in a plug for the old format,” Clement said. “I think there was something to the idea of get it done in an hour. Most legal issues, you really can explore the important points in an hour.”

The expanded arguments have tended to “magnify” the advantage of the side in a case in which the United States is arguing or supporting, Clement added.

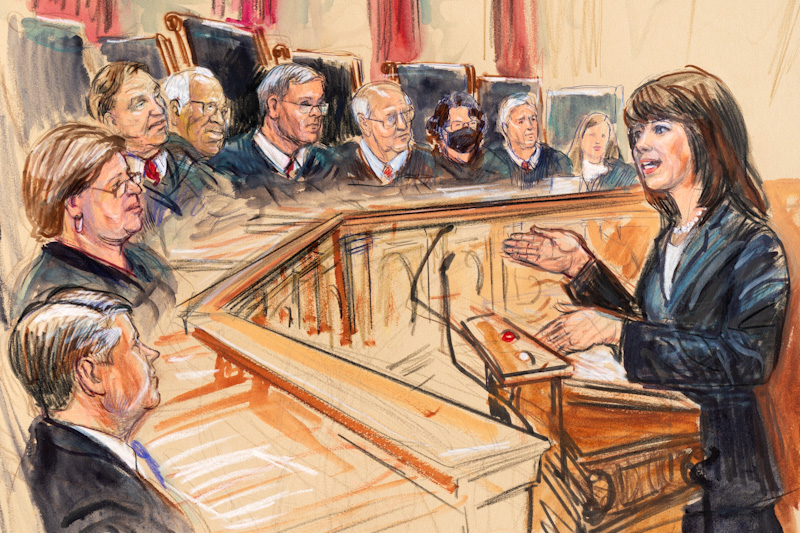

This artist sketch depicts U.S. Solicitor General Elizabeth B. Prelogar, right, presenting an argument before the U.S. Supreme Court in November 2021 in Washington, D.C. (Sketch by Dana Verkouteren via the Associated Press)

This artist sketch depicts U.S. Solicitor General Elizabeth B. Prelogar, right, presenting an argument before the U.S. Supreme Court in November 2021 in Washington, D.C. (Sketch by Dana Verkouteren via the Associated Press)

Growth of the emergency docket and Red State, Blue State briefs

The session’s moderator, Judge Patricia A. Millett of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit, was not afraid to ask about another slightly controversial topic, the relatively recent expansion of the court’s emergency docket, also known as the “shadow docket.”

The court has faced an increase of parties asking it to rule on or block lower court rulings on matters at a relatively early phase of litigation. An increase in the frequency of federal district judges issuing nationwide injunctions blocking administration policies, especially during the Trump and Biden administrations, has added to the growth of that corner of the high court’s workload.

Prelogar noted that in five years as an assistant to the solicitor general, she never was called upon to work on an emergency application to the high court.

“Frankly, it would terrify me because you have to write a brief overnight, practically,” she said. Now, when she interviews job candidates for her office, she asks whether they have experience working on emergency matters. At least the court has more recently set several high-profile cases from the emergency docket for argument and full consideration.

“I think that is helpful for the government to be able to put forward our best arguments,” she said.

Gershengorn said the court’s willingness to put some such cases on the argument calendar was an acknowledgment that its handling of some emergency matters “was hurting its legitimacy.”

Millett also noted the growth of filing of amicus groups by large numbers of Republican- or Democratic-led states, as well as certain states or groups of states seeking standing to challenge administration policies.

Katyal said that the rise of state solicitors general familiar with the work of the U.S. Supreme Court has created “a kind of counterweight to the United States solicitor general’s office.”

“I think in every case I’ve been in for the last couple of years, there’s a red state brief and a blue state brief,” he said. “And that’s a real change.”

While Katyal said that was mostly a positive thing, Clement said, “I’m a little less sure if it’s a good phenomenon.”

“I’ll be careful here because I do represent states from time to time,” he said. The conversation had taken note that in 2007, in Massachusetts v. Environmental Protection Agency, the court had ruled that the states have “special solicitude” under the court’s legal standing analysis. Republican-led states have challenged many Biden administration positions in major cases.

“I’m sure a lot of liberals were sort of cheering for the Supreme Court when it recognized Massachusetts’ standing to … prompt a Republican administration to do more about climate change,” Clement said. “But a few Texas lawsuits later, maybe it’s not such a great thing.”

Prepping for the big day and a little help from the kids

The discussion wasn’t all super serious. Millett asked the panelists about their preparation rituals.

Prelogar, as has been widely reported, tries out her opening on her young children at dinner the night before an argument, and they then rate her on a scale of one to 10, even if they don’t always understand the issues in the case.

Katyal does something similar with his sons, who are young adults now but were under 10 when he was acting solicitor general.

“It turns out if you can explain your argument to a 5-year-old or a 9-year-old, it just does help you crystallize what your overall point is,” he said.

Francisco said he goes to the cinema the day before an argument.

“I find some mind-numbing action movie that completely takes my mind off the case,” he said.

After Prelogar referred to her office as the “Navy SEALs” of the Justice Department, Francisco recalled that he instituted a voluntary “boot camp” program for him and his staff members to exercise on the National Mall, across the street from the department.

The boot camp instructor’s husband was in the U.S. Army, Francisco recalled, and she told him she was going to bring Army T-shirts for the boot campers to wear while they worked out. Francisco nixed that idea. “I said, … there’s no way we’re doing that because if tourists are walking down the mall and looking at us and thinking, the country’s depending on them?” he said. “It’s a disaster.”

A serious but special role

The panelists tended to agree that the solicitor general and the office has a special role within the executive branch and the legal system as a whole. They didn’t really embrace the decades-old notion of the solicitor general as the “10th justice,” someone almost on par with the life-tenured members of the Supreme Court.

The justices themselves certainly don’t view the solicitor general in those terms, Prelogar noted.

Clement agreed.

“I don’t think it works to say, ‘Hey, we’re the 10th justice, we’re quasi-independent, you know, buzz off; don’t ask me what I’m doing,’” he said.

There is a “sort of a mystery that this sense of independence persists” with the office, said Clement. There is still an organization chart in which the solicitor general reports to the attorney general (and a couple of other high-ranking Justice Department deputies) as well as needing to keep the White House informed, he said.

“Ultimately it is in the interest of every administration to take a long view of these things and really look out for the institutional interests of the executive branch and not for any particular party or even the current occupant of the White House,” Clement said. “So that’s part of it. But then it does create this dynamic where the relationship between the White House and the attorney general and the solicitor general are all incredibly important.”

Prelogar said it was critical “to try to adhere to the traditions of the office and respect the process and recognize that it is a big federal government with a lot of cross-cutting interests.”

“The only way that you are going to ensure you make the best decision possible for the government as a client,” she said, “is to actually follow this really rigorous process of soliciting views, hearing all sides, being open-minded about it, drawing on the expertise from every corner of the government, and recognizing that the reason we have this process in place is because it works and it leads to the best decision making possible.”

Write a letter to the editor, share a story tip or update, or report an error.