'Show the Brief': Lawyers can be better communicators by bringing visuals to their briefs

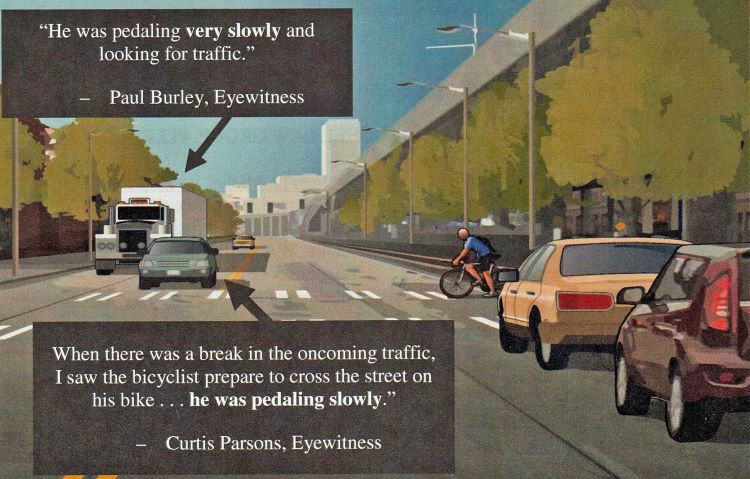

Summarizing key deposition testimony in a brief. Images courtesy of William S. Bailey.

My decision to teach law more than 40 years ago has had the single biggest impact on my professional development. I made the move after working as a public defender in Seattle and as an assistant attorney general. I wanted to deepen my trial skills and thought teaching could help me.

I answered an ad in the state bar journal seeking a part-time trial advocacy instructor at the Seattle University School of Law. I took the job, loved teaching and eventually moved on to the University of Washington, where I landed a full-time position in 2011. Besides the emotional richness of the connections to my students, standing and delivering in the classroom put a structure around my deeply held goal of lifelong learning. The questions my students asked always revealed how much I had to learn, prompting me to reach out in all directions to get the answers.

As a teacher, I learned a lot from judges. Because I often worked with judges in clinical skills courses, I had the benefit of a much more relaxed, open connection with them than I could have in the formality of a courtroom. This candid dialogue gave me a much greater appreciation for just how demanding the life of a trial judge is, particularly in our chronically overloaded and under resourced state trial courts.

The biggest complaint by far from the judges was the poor communication skills, both written and oral, of most lawyers who appeared before them. Plain and simple, it was a matter of quantity over quality. We took far too long to say too little, seemingly oblivious to the information needs of both the judge and the jury, often leaving them in “never-never land,” as one judge put it. Judges told me they often found themselves faced with stacks of legal papers landing on their desks with a resounding “thump” (or more likely, a virtual thump on their computer monitors).

Given the steadily mounting pressure on lawyers to file motions, it is little wonder that trial judges have been pushing back on brief length, wise to our tricks of trying to game the page limit by creatively crunching font size.

We lawyers are smart, dedicated people, lovers of language, incredibly dedicated to protecting our clients’ interests. A great deal of emphasis is placed on legal writing in law school. How could we communicate so poorly in the briefs we file? What could I do as a teacher to help my students do better? I started reaching out systematically for the answers.

I had the opportunity to take an in-depth look while filling in for a colleague who taught legal writing. Although there were subtle differences of approach among the many textbook choices, all of them focused heavily on matters of form. Understanding the great importance of this—where even a single typo in a brief can diminish a judge’s regard for a lawyer—nonetheless, the lack of attention to the communication aspects was deeply troubling.

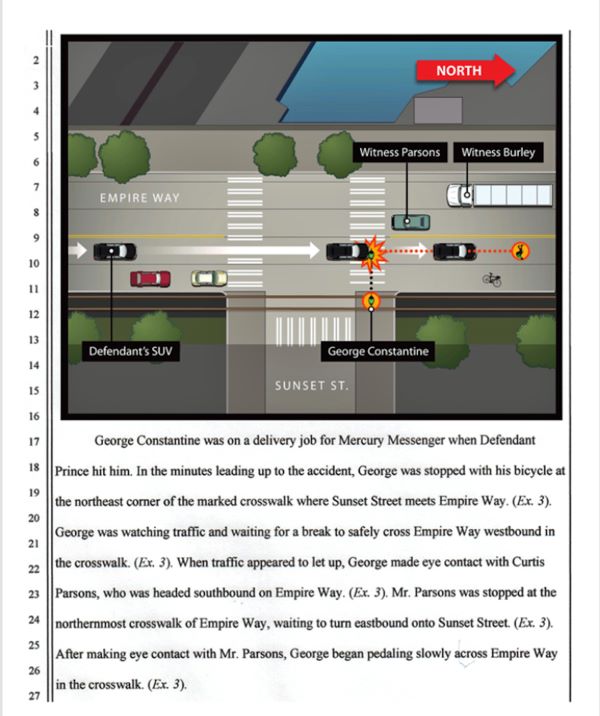

Embedding an overhead scene diagram into a brief.

Embedding an overhead scene diagram into a brief.

It’s all about the story

Behavioral psychology and neuroscience have repeatedly proved how critical the story is to every form of writing. We are all instinctual gut processors by nature, using our values and life experience to filter and evaluate information. Stories provide the necessary framework for understanding and learning. The picture superiority effect further enhances the impact of a story, as our brains more readily absorb, code and understand visual information.

As I dove deeper into the research on effective communication, I found an appalling lack of attention to visual storytelling. The form-dominated approach to writing in legal education is an outlier. Other professional schools are all over the visual, storytelling and psychologically informed approaches to writing.

I reached out to colleagues on campus in other disciplines, including the fields of psychology, neuroscience, communication, journalism, graphic design and theater. To sharpen my own storytelling skills, I signed up for night courses in creative nonfiction writing. The more I learned, the less I realized I knew. While humbling, the new information was exhilarating, pointing to a new and better way. Bit by bit, I created my own legal writing curriculum, one that tracked with what is happening everywhere else in the world.

In the classroom, I repeatedly emphasized Aristotle’s admonition to “know your audience.” Judges desperately want and need us to teach them about a case. E.B. White’s admonition in The Elements of Style is particularly critical here, given the often dense, dry, technical and somewhat boring nature of legal analysis: “… the reader [is] in serious trouble most of the time, floundering in a swamp … it is the duty of anyone attempting to write English to drain this swamp quickly and get the reader up on dry ground, or at least to throw a rope.”

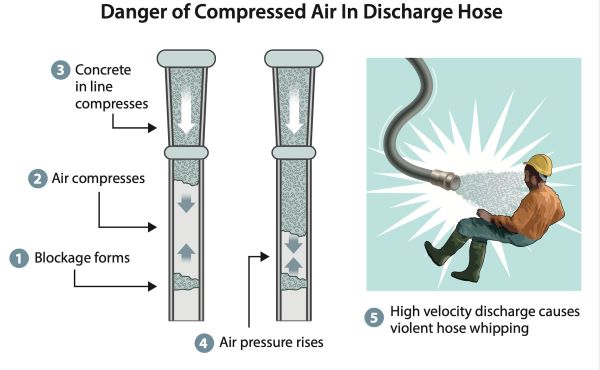

As research shows, words alone are not nearly as effective as a combination of words and pictures. Other professions seem to understand this. Word people to the core, few of us consider images as part of our job description. The visual elements of legal writing became an important part of my teaching approach, showing how to combine words and images on the pages of a brief, rather than words only, with images in the attachments.

My goal is not to try and turn students into graphic designers, just to have them apply their legal knowledge to the image creation process. My longtime illustrator Duane Hoffmann explained our role: “It is not important that you be able to draw well. You just need to tell someone like me what to do. I have no idea what matters most to a legal story. Your role is the same as an art director in an ad agency.” A light bulb went on. I smiled. “Art director. I like that.”

William S. Bailey.

William S. Bailey.

Learning to get visual

To be a good legal art director, conscientiously applying the rules of evidentiary foundation, I needed to understand the basic principles of graphic design. How computer images were created was a total mystery to me. If I could not explain this to judges, how could I expect them to allow their use in briefs? Thankfully, many books are geared to this, helping non-graphic designers like us. These too became part of my teaching tool kit. As visually sophisticated visual natives, my students easily absorbed all this. I tied it to what they already did in everyday life: “You put images with stories in your Facebook and Instagram posts all the time.”

Over the past decade, my persuasive writing classes steadily have shifted to these visual storytelling techniques. Along the way, I have reached out repeatedly to many federal and state trial judges, vetting all this. They repeatedly confirmed I was on the right track. When done in a careful, meticulous, professional manner, the visual approach to brief writing is the answer to a busy trial judge’s prayer. Instead of volumes of attachments at the end of a brief, the most important images are right there embedded in the text, where they are the most helpful.

Best of all, the regular incorporation of images in a brief applies the adage “A picture is worth 1,000 words.” Images are like information compressing algorithms in the computer technology world. And as brain research shows, they are more quickly and accurately processed than words. For example, no matter how artful, describing a scene in words will never create a sharp mental image for the reader. This problem is completely avoided with a picture in the brief.

In the 1990s, the New York Times did extensive studies of reader behavior, confirming that even their erudite readers always looked at the pictures first, which heavily shaped perception of the written story. The Times got the message loud and clear, stepping up the visual interest of the paper. We need to follow its lead.

Explaining technical information in a brief.

Explaining technical information in a brief.

Combining the litany of judicial complaints on traditional briefing with my own hard-won lessons in years of practice and teaching, something clearly has to change. Most critical legal issues are decided on the basis of our writing, not the dazzling courtroom oratory we see on television.

I felt so strongly about this, I decided to write a book, Show the Brief, which I hope will be helpful to a profession I have loved and believed in my entire adult life. It is critical that we step up our written game with a crisp and fully visualized communication style, benefitting both our clients and our overworked trial court judges.

After a 40-year career as a civil and criminal trial attorney, William S. Bailey became a full-time professor from practice in 2014. In addition to Show the Brief, his other books include Show the Story: The Power of Visual Advocacy (with Robert W. Bailey); Law, Science and Experts: Case Problems and Strategies, Law, Science and Experts: Civil and Criminal Forensics (with Terence J. McAdam); and Cross Examination Handbook (with Ronald H. Clark and George R. “Bob” Dekle). He also has written several NITA case files based on his own trials in practice.