New database tracks gender-based violence sentencing decisions in the Pacific

Image from Shutterstock.

To Loukinikini Vili’s knowledge, no one in the Polynesian island nation of Samoa had ever analyzed gender-based violence sentencing decisions to identify bias and discrimination.

That’s why an invitation from the International Center for Advocates Against Discrimination caught her attention. Not only could she access its new database of thousands of domestic and sexual violence cases in Samoa and other countries in the Pacific, but as part of one of its first “train-the-trainers” cohorts, she would also learn to help advocates hold judges accountable for their decisions.

“The training not only showed us information about the trends in sentencing decisions, but it definitely got us thinking about a lot of things,” said Vili, a lawyer and the director of human rights at Samoa’s Office of the Ombudsman/National Human Rights Institution. “Some of them include, what was the judge thinking when they gave the decision or what type of information was provided to the judge that influenced their decision?

“When we were analyzing some of Samoa’s gender-based violence sentencing decisions, we were also able to identify and discuss different gender biases and discrimination and how patriarchy and toxic masculinity in Samoa drive gender-based violence.”

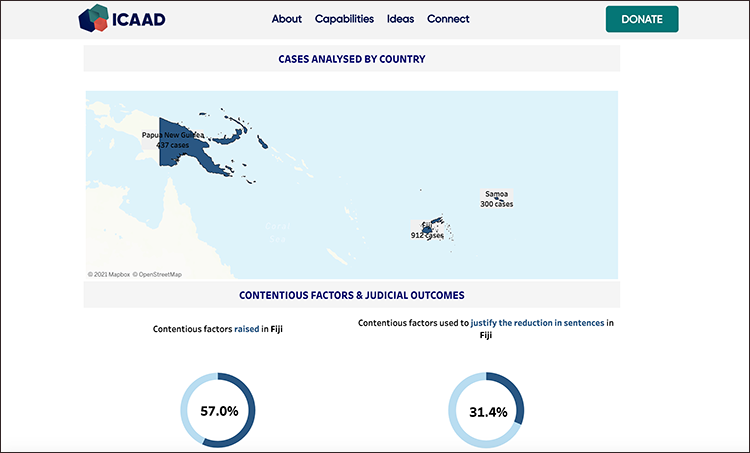

Vili joined other gender justice advocates last week at ICAAD’s virtual launch of its TrackGBV Dashboard, which, in addition to Samoa, includes data for Fiji and Papua New Guinea. The nonprofit organization began exploring the significant prevalence of gender-based violence in the Pacific in 2013, and it plans to soon add cases from Vanuatu, Solomon Islands, Tonga, Marshall Islands and Nauru.

Among the data compiled for each country, the TrackGBV Dashboard highlights contentious factors in gender-based violence cases that could discriminate against survivors when used in mitigation by the court. These include gender stereotyping; customary practices, such as forgiveness ceremonies; and other factors, such as a perpetrator’s religious activities.

“It’s one thing to have an isolated example of a case with its own unique circumstances, and it’s another to build an evidence base of 20 years of caselaw that tracks the patterns and impact of biased judicial decision-making,” said Erin Thomas, ICAAD policy and research coordinator, who is based in Auckland, New Zealand. “We found that when women and girls access the formal justice system in gender-based violence cases, perpetrators have been shown to receive disproportionately low sentences or no custodial sentence at all.

“The TrackGBV Dashboard begins to tell the story of how that happens in each jurisdiction.”

As one example, the TrackGBV Dashboard shows that contentious factors were raised in 57% of Fiji’s 912 gender-based violence cases and used to justify a reduction in perpetrators’ sentences in 31% of those cases. Breaking down contentious factors further, gender stereotypes were responsible for reduced sentences in more than 36% of cases.

In addition to sentencing information, ICAAD contains in its database statistics about survivors and judges. This includes survivors’ ages and whether anonymity was granted to them as well as whether judges were lenient with first-time offenders or cited medical reports in their decisions.

Sentencing by the book

Jacqueline Song and her Clifford Chance colleagues worked with ICAAD to develop a sentencing handbook.

Jacqueline Song and her Clifford Chance colleagues worked with ICAAD to develop a sentencing handbook.Jacqueline Song, an attorney in Clifford Chance’s Sydney office, spoke at last week’s ICAAD event about her firm’s pro bono involvement with the TrackGBV program. Along with working with the nonprofit to develop a first-of-its-kind sexual and gender-based violence sentencing handbook in 2018, she and her colleagues assisted with its “train-the-trainers” materials and helped analyze cases for the new dashboard.

“Our London team reviewed around 2,000 cases since July of last year, and what’s most exciting to note here is it was actually the GBV handbook that we developed earlier on and the methodology used therein to guide the large-scale caselaw analysis that has made its way to the dashboard that we see today,” Song said.

Now that Vili has learned how to use the TrackGBV Dashboard, she plans to share data from Samoa with individuals and organizations that can use it to facilitate change. She hopes to provide it to judges and possibly partner with them in a joint capacity building workshop. She also wants to engage others who could impact jurists’ decisions, including the attorney general, prosecutors, police and nongovernmental organizations.

“How do we envision others in Samoa reacting to the GBV data?” Vili asked. “I believe others may react the same as we did … this will be the foundation of informing the necessary changes in mindsets and attitudes, policies, programs and activities, and of course, in sentencing decisions to remove judicial bias and discrimination.”

Expanding ICAAD’s reach

In the past year, ICAAD began exploring how the TrackGBV program could support access to justice in other regions, such as the Caribbean.

Justice Jacqueline Cornelius worked to draft gender protocols for the Barbados judiciary.

Justice Jacqueline Cornelius worked to draft gender protocols for the Barbados judiciary.Jacqueline Cornelius, a justice of the High Court of Barbados, spoke at last week’s program about her work to draft gender protocols for the judiciary in 2017. She said she also served as a member of the Sexual Offenses Advisory Committee, which in the same year helped the Judicial Reform and Institutional Strengthening Project and other stakeholders develop the Model Guidelines for Sexual Offense Cases in the Caribbean Region.

“It’s really an exciting prospect throughout the region to see how are we doing,” Cornelius said. “We have the protocol, we have the sexual offenses guidelines, but is it actually seeping into the judiciary? Is this being shown in their decision-making?

“We have the groundwork. We have started training our judges. We have started to do the research. We feel that the next step is precisely this kind of project, where we can say to our people and to the state, ‘Look, this is what is happening in the courts, this is how it is happening and this is how we can try to stop it.’”