Chicago lawyer writes about being GOAT at New Yorker Cartoon Caption Contest

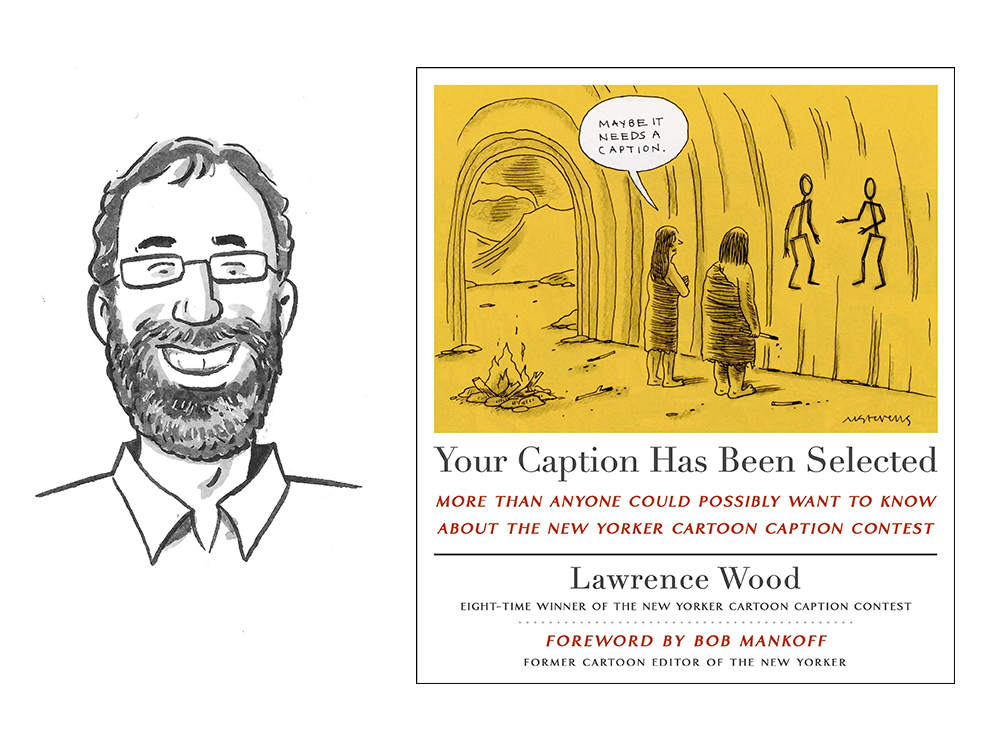

With eight first-place entries, Lawrence Wood has won the New Yorker Cartoon Caption Contest more times than any other entrant. (Art by Benjamin Schwartz)

There’s a cartoon with a dolphin panhandling on a street corner. A man is reaching into his pocket to give it money. His female companion looks irritated. Chicago lawyer Lawrence Wood put words to her displeasure: “If he’s so damn intelligent, let him get a job.”

With that line, Wood won the New Yorker Cartoon Caption Contest in 2007. He’s repeated the feat seven more times—and placed second or third in seven other competitions.

Now in its 25th year, the esteemed literary magazine’s weekly competition features a wordless single panel cartoon—often displaying disparate frames of reference. Contestants submit a caption for the image. The publication’s editors choose their three favorites from the 5,000 to 10,000 entries. Online public voting—with generally more than a half million votes cast—determines the winner.

There is no cash prize for winning, but the bragging rights are priceless.

Wood is the contest’s most successful participant—by a lot. The contestant in second place, he says, has won three times.

In June, Wood’s book, Your Caption Has Been Selected: More Than Anyone Could Possibly Want to Know About the New Yorker Cartoon Caption Contest, was published by St. Martin’s Press.

In a recent interview, he offered advice to participants to increase their chances of winning and shared how captioning is a little like lawyering. And there’s that accolade once bestowed upon him by U.S. Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia.

The book was the idea of Bob Mankoff, the New Yorker’s former cartoon editor and creator of the caption contest. Writing in its foreward, Mankoff calls Wood the contest’s GOAT—or the greatest of all time—and believed that he deserved to be better known for his achievement.

But Mankoff—who had the publishing contacts to make the idea a reality—wanted Wood to provide more than just tips for aspiring winners. He thought Wood should go deeper, offering “reflections on what can be learned from the contest about humor, good writing, creativity and even what it means to be human in the age of artificial intelligence.”

A funny family

When asked where his humor comes from, the Syracuse, New York, native doesn’t hesitate: “My parents and sister were all funny.”

He also describes a youth spent reading MAD and National Lampoon, watching the Mary Tyler Moore and Bob Newhart shows, and listening to comedy albums by Bill Cosby, George Carlin and Woody Allen.

“I don’t think one can learn to be funny just by reading, watching and listening to comics,” Wood says. “But it taught me how to understand comic rhythms and tell a joke.”

Following graduation from Connecticut College, Wood headed to Washington, D.C., where he did a two-year tour of duty as a paralegal at Fulbright & Jaworski. The University at Buffalo School of Law came next.

While studying in Western New York, Wood read about the Southern Poverty Law Center’s success in bankrupting the United Klans of America in Alabama following the group’s lynching of a Black man. The seed was planted for a career in public interest law.

Wood spent over three decades with Legal Aid Chicago, the Midwest’s largest provider of free civil legal services to the poor. He recently moved to Legal Action Chicago, which does the class action and legislative advocacy work not permitted by Legal Aid due to its receipt of federal funding.

For 22 years, Wood ran a clinic in law and poverty at the University of Chicago Law School. In 2008, Justice Antonin Scalia, speaking at a Federalist Society event in the city, commented that the law school had lost its way as a rigorous and conservative institution.

As proof, Scalia—a Harvard Law alumnus—stated that he “took nothing but bread-and-butter classes, not ‘Law and Poverty.’” The justice added: “Take serious classes. There’s so much law to learn. Don’t waste your time.”

“I wear that as a badge of honor,” Wood quips.

Does it help to be a lawyer?

Wood says that the caption contest, at its core, is like litigating. “Your job to is to use language to persuade a judge that what you have to say is better than your opponent’s argument, he says. “You are trying to make sense of this bizarre drawing. Lawyers are taught to take complicated situations and make connections that other people might not notice.”

He adds: “A good caption eliminates every unnecessary word to make its point” This, he adds, is “not unlike what lawyers do when streamlining legal arguments.”

But despite this, Wood notes that he also knows “a lot of really smart lawyers—lawyers who are a lot smarter than I—who are terrible at the contest.”

How to win

Over 29 brief chapters, the grand champion offers tips to increase one’s chances of seeing their caption appear in the New Yorker.

Lawrence Wood’s book Your Caption Has Been Selected was published by St. Martin’s Press in June.

Lawrence Wood’s book Your Caption Has Been Selected was published by St. Martin’s Press in June.For starters, he advises not using an exclamation point unless your caption is an actual exclamation. “A joke is not funnier with an exclamation point,” Wood says. He surmises that about 20% of the weekly entries contain an unnecessary exclamation point.

In a chapter titled “Everything Matters,” Wood writes that “everything that appears in a drawing is important. The cartoonist put it there for a reason and you shouldn’t ignore it, but many contestants disregard this rule.”

Wood cautions that captions should not be too predictable. “Resist the urge to submit one that comes to mind immediately,” he writes. Besides, he adds, “if it’s obvious to you, it will be obvious to hundreds of people you’re competing against, which means your entry will likely get lost in the sea of similar or even identical submissions.”

He also recommends taking advantage of the fact that the judges are seeing countless similar entries. For them, he says, this can be “numbing.” So “if you can surprise the editors with something that makes them see the drawing from a perspective they never imagined, I think that really increases your chances of making it to the finalist round.”

While Wood has a lot to say about how to win the distinguished contest, participants should never forget this one piece of overarching advice: “Your caption should be funny. You don’t want someone to just admire it; you want someone to actually laugh.”

It’s a long shot

Because he’s won the contest so many times, I ask Wood if he is sometimes surprised that his entry didn’t get chosen as a finalist. “Weekly,” he says, laughing. “I imagine that many people participating in the contest feel the same way.”

But with thousands of entries submitted every week, “it’s inevitable,” he says, “that some of the best captions may get overlooked. Nevertheless, the majority of finalists are good and many are great.”

Despite his record of success, Wood has lost almost 900 contests. So every time he’s disappointed, that what he thought was a sure winner isn’t selected, he reminds himself “why didn’t I expect this.”

For participants of the caption contest looking for tips to improve their chance of winning, Wood’s words are stone-tablet worthy.

But as was Mankoff’s charge, it is much more than a how-to guide. Wood takes a deep dive into the history of the contest and its inner workings. And with 175 New Yorker cartoons included, the author looks at cartoon humor with a scientific eye.

Wood concludes that Your Caption Has Been Selected asking whether artificial intelligence can develop a sense of humor and even win the caption contest. Computers have been given the task, and Wood provides some results of their efforts. They are “not great,” he says, “but not terrible for a machine.”

Wood shares that one AI expert who has studied the question in detail came to the conclusion that “even the fanciest AI today cannot really decipher what’s going on in New Yorker captions.”

That’s “reassuring,” Wood says, “but the day when a computer program can understand humor, and even win the caption contest, may not be that far off.”

Randy Maniloff is an attorney at White and Williams in Philadelphia and an adjunct professor at the Temple University Beasley School of Law. He runs the website CoverageOpinions.info.