Liberating criminal justice data: How a Florida law provides a blueprint for the nation

Image by Stephen Finn via Shutterstock.com.

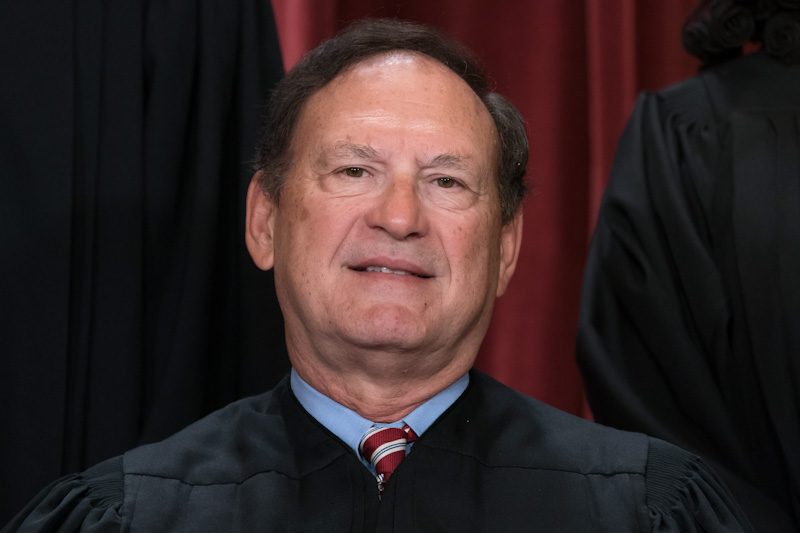

In a self-imposed Sisyphean task, the team at Measures for Justice travels the U.S. unearthing, collecting and publishing criminal justice data.

The nonprofit’s mission is to create a national system of performance measurements of local criminal justice systems—from arrest to post-conviction—in each of America’s 3,141 boroughs, counties, independent cities, parishes and the District of Columbia.

Even though they are collecting digital files, Measures for Justice visits sheriffs’ and prosecutors’ offices in teams of two to find data and build trust.

“There’s a huge amount of anxiety and ambivalence that agencies have around sharing data,” says Mikaela Rabinowitz, director of national engagement and field operations at the organization.

This is due to the limited capacity to collect and analyze existing data, which leads many to be unaware and worried about what the data will say, Rabinowitz adds. But once the data is collected and released, local leaders can dive in.

“Their data tipped us off that we had an issue we didn’t know about,” says Christian Gossett, district attorney for Winnebago County, Wisconsin.

In an early state to receive the Measures for Justice treatment, Gossett says his office found previously unknown racial disparities in the uptake of diversion and that indigent people charged with low-level crimes were languishing in jail, unable to pay a $500 bond.

Today, he says, more people are being released quicker pretrial, and he’s working with researchers to improve equity in diversion, thanks to the initial data made available by Measures for Justice.

In 2017, the nonprofit, based in upstate New York, released data from its first six states—Florida, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, Utah, Washington and Wisconsin. While varying state to state, the data includes the time it takes to resolve a felony case, the use of jail beds and the length of prison sentences. The organization expects to release another 14 states’ data by 2020.

Intended as a data collection exercise, Measures for Justice’s work has unintentionally sparked novel legislation in Florida. Realizing the limitations of its criminal justice data, state leaders in Florida passed a first-of-its-kind law that will collect about 140 data points across the criminal justice continuum—from arrest to release—standardize that data across the state and publish it online.

Currently being implemented in two pilot counties in Florida, advocates of the new law anticipate that more data will empower local criminal justice reform and act as a blueprint for other states. However, failed implementation can cost a county its court and law enforcement budgets, and, critics say, laws like this can negatively affect people in the criminal justice system.

BARRIERS TO SUCCESS

The state of criminal justice data in the United States is a grab bag of digital and paper records hidden away in various bureaucracies with no standard set of definitions found across the local, state and federal systems that administer criminal justice.

While the federal government collects and standardizes some local data, such as the FBI’s annual Uniform Crime Report, it is not comprehensive, and local governments are not required to fork over this data, leaving holes.

“As I was researching for my book, Ordinary Injustice, I kept running into people who really could not see the forest for the trees,” says Amy Bach, an attorney who founded Measures for Justice in 2011.

For example, Bach found a DA who didn’t know if he had prosecuted a domestic violence case in 21 years. She also came across a judge who handed down high bail amounts for minor crimes that were out of step with what other judges were doing.

“Where was the oversight? Who was noticing any of this? The harm here is that if people can’t see what’s wrong, they can’t fix it,” she says.

With a ragtag team of two and an anonymous donation, Bach says she started the organization “feeling our way forward, trying to figure out how to do as much as we could on almost nothing.” Today, the organization has a staff of more than 30 people and has received significant funding from major donors like the Ford Foundation, Google.org and Silicon Valley power couple Mark Zuckerberg and Priscilla Chan.

Now, Measures for Justice’s work has caught a wave in Florida, which is experiencing a bipartisan movement to improve the state’s overburdened and expensive justice system. At the end of 2016, the state was fourth in the country for total number of adults incarcerated and under probation and parole, according to the U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics. In the 2017-18 fiscal year, Florida spent $2.4 billion on corrections and another $570 million on juvenile justice administration.

Image from Shutterstock.com.

Image from Shutterstock.com.

Ahead of most states, Florida already collected case information including names, charges and sentences, among other factors. However, the state did not require court clerks to provide any information about bail or pretrial release, explains Gipsy Escobar, Measures for Justice’s director of research innovation. As well, arrest data did not capture ethnicity, leaving Latinos—25% of the state’s population—categorized as white or black.

Going into effect statewide Jan. 1, 2020, new data will be collected across courts, corrections, police, prosecutors and public defenders. While not retroactively affecting historic data, the new dataset will include charges and case outcomes, and any alternative programs used in lieu of trial, conviction or incarceration.

With help from Measures for Justice, pilots are currently underway in Pasco and Pinellas counties, where software systems are reflective of the state’s other counties. The stakes are high: Failure to comply can cost a noncompliant agency its entire budget for five years.

“It’s a very complicated law and process to collect all that information,” says Paula O’Neil, clerk of the circuit court and comptroller of Pasco County, “but we certainly understand the need for it, and we believe that the information will be very valuable.”

The success or failure of the law will largely fall on the shoulders of the state’s court clerks, like O’Neil. Under the law, they are expected to collect, standardize and send more data than any other local agency to Florida’s Department of Law Enforcement for publication.

A systemic problem in collecting criminal justice data, even within a single state, is the lack of standards.

“It’s extremely important that there be uniformity in the definitions,” says Ken Burke, clerk of the circuit court and comptroller of Pinellas County. To improve the process, the legislature this spring updated the law by requiring a uniform, statewide arrest affidavit, which Burke says is necessary for the success of the data law because arrests are often the first point of data collection in the criminal justice system.

Even with standardized forms, the law’s outcome can still be confounded by how data is defined. Take a prosecutor’s charge, for example. The subjective world of prosecutorial discretion means one prosecutor’s burglary can be another’s trespass. This lack of consistency can create problems when data starts to be compared between counties, Burke says.

Even with these challenges, Burke’s and O’Neil’s teams have soldiered on, implementing the immense law with no extra funding.

At the state level, the Florida Department of Law Enforcement, which will publish the data, hasn’t had a way to accept the information sent from the counties, so early legislative deadlines for posting some of the data have been missed, according to Burke. A representative for the department declined to comment.

Read other stories from the ABA Journal’s Marked for Life series.

COLLATERAL CONSEQUENCES

As Florida removes barriers surrounding criminal justice data, others are taking note.

“This work breaks up the soil and creates a more fertile landscape for building better analysis,” says Clementine Jacoby, executive director of Recidiviz, a nonprofit that helps criminal justice agencies improve their data infrastructure and analysis. “It would certainly make our work easier if this legislation was replicated across the country.”

Escobar at Measures for Justice says legislatures in California, Colorado, Connecticut, North Carolina and New York have passed or are considering legislation to increase or study criminal justice data collection.

With this increased attention, some worry a law like Florida’s removes meaningful safeguards.

In other states, it “takes hours and hours of labor to overcome all the legal barriers to linking [datasets] up,” says Jeffrey Butts, director of the Research & Evaluation Center at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice in New York.

“I appreciate that all these barriers exist,” Butts says. “[If] all the data were integrated in the way that [Measures for Justice] dreams of, it would be horrible because we would use it to increase the lifelong stigma of minor offenses.”

Called “collateral consequences,” numerous studies show that even an arrest without a charge or conviction can affect a person’s ability to access education, employment and housing. Amassing more data, like in the case of Florida, can increase harms and make people more vulnerable to identity theft or deportation, Jacoby says.

Florida already leads the country in the number of personal identifiers released in online criminal record data, according to forthcoming research by Sarah Lageson, a professor of criminology at Rutgers University. But factors like gang affiliation and immigration status will be easier to find with the new law’s implementation. Juvenile cases remain out of public view.

Rabinowitz at Measures for Justice acknowledges these challenges but says that low-quality criminal justice data also hurts people in the criminal justice system. By example, she says the movement to create automatic criminal record clearing in California is held up because local data is not good enough to support the policy.

Whether good or bad, a law like that in Florida will provide scrutiny of itself through its release of more data.

“The criminal justice system is the lone standout keeping data and analytics out of its system,” says Gossett in Wisconsin. “At the end of the day, the numbers tell you how things are going.”