Lawyer pens book about multiple personality disorder murder case that haunts him

David Savitz.

David Savitz met his client for the first time in a holding area of a Denver courthouse. When he looked at the young man charged with murdering his parents, Savitz thought he resembled a Calvin Klein model with his thick blond hair, muscular physique and “Scandinavian good looks.”

Ross Carlson, 19, stood up to shake his new lawyer’s hand. He was polite, articulate and seemed otherwise normal. Carlson kept apologizing for the way he looked in his loose-fitting orange jail jumpsuit, which struck Savitz as odd.

So began the unusual and complex relationship between Savitz and Carlson, who would later be diagnosed with multiple personality disorder and claim he was insane at the time he gunned down his parents on a rural road in Colorado in 1983.

The case got widespread media attention, drawing comparisons to the story of Sybil, a woman diagnosed with multiple personality disorder and the subject of a bestselling book and TV miniseries in 1976.

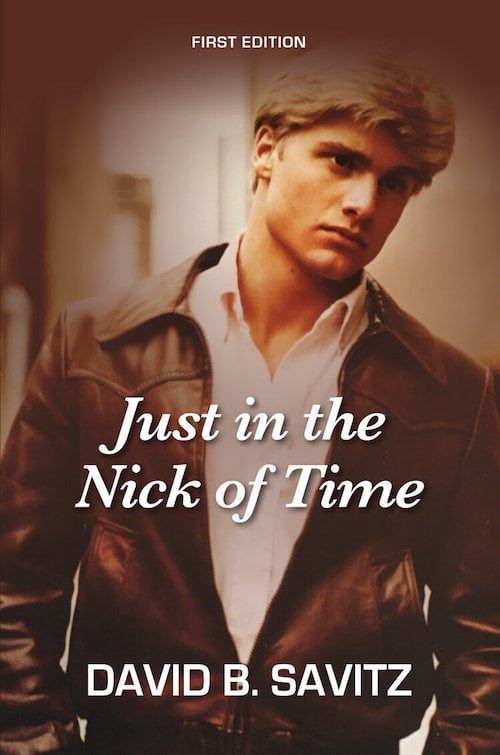

Savitz, 78, recounts his experience defending Carlson in a new book 30 years in the making. Just in the Nick of Time is part memoir, part courtroom drama and part medical mystery that examines whether his handsome, charming client had a real psychiatric disorder or was a crafty manipulator trying to fake his way out of a murder conviction.

“In 1991, I began writing an outline for the book, but at the time I still had a very heavy criminal practice, as well as some civil work” says Savitz. “It was a protracted effort.”

A history of strange behavior

Ross Carlson, the only son of schoolteachers Rod, 37, and Marilyn, 36, was arrested for shooting his parents, execution style, after asking them to go for a car ride to a remote area outside of Denver. Prosecutors said Carlson killed them so he could inherit their money.

A judge initially appointed a public defender to represent Carlson, but he wanted a private lawyer and contacted renowned criminal defense attorney Walter Gerash. Although Carlson had no money, he believed he was entitled to his parent’s estate because he was presumed innocent. That’s when Gerash called Savitz, his longtime friend and protégé, and he asked Savitz to get a court order to release the funds.

A judge agreed Carlson was entitled to the money, and Gerash asked Savitz to stay on the case, leading them on a journey neither could have imagined, Savitz says.

The lawyers learned their client previously had been arrested and ordered to receive psychiatric treatment after he had placed an ad in a mercenary magazine seeking to buy explosives. Police were alerted and arranged to have an undercover officer meet Carlson for the purchase. He was arrested and the court recommended psychiatric therapy. During therapy, Carlson told Dr. Gregory Wilets that his parents had been unmarried teenagers ill prepared for parenthood. Carlson said he felt he was a burden and wanted to relieve his parents of debt by blowing up the house so they could collect insurance.

Savitz and Gerash consulted with Wilets and hired other psychiatrists to examine Carlson. They reported Carlson had suffered from chronic loneliness, depression, suicidal thoughts, and he had developed nine other personalities. Carlson told the doctors his parents traumatized him during potty training, and as he grew older, they increasingly demanded perfection and subjected him to psychological torture.

Savitz says he initially was skeptical about his client really having multiple personality disorder, also known as dissociative identity disorder. But he began to change his mind after watching a psychiatrist interview Carlson in person and on videotape. Savitz recalls being in awe as he saw Carlson transform into different people—some polite and docile, others aggressive. “I’m saying to myself, ‘This is wild. This is very powerful,’” Savitz says. “And I say this is the exact kind of evidence we need to present to a jury.”

Still, Gerash was reluctant to use the multiple personality defense, thinking it was too bizarre and something a jury would not believe. “Between Walter and me, he was more skeptical,” Savitz says.

The personalities go to court

The lawyers requested a competency hearing, intending to present videotaped evidence showing Carlson adopting different personalities. But when media demanded release of the tapes, the lawyers decided instead to have doctors testify about the sessions, eliminating the need to enter the tapes as evidence and make them public, which if broadcasted and sensationalized could taint the jury pool.

During the hearing, Carlson displayed various personalities and had violent outbursts, forcing officers to restrain him. Psychiatrists for the defense testified that Carlson’s multiple personality disorder developed from long-term parental abuse. One psychiatrist testified that Carlson told him that when he killed his parents, it wasn’t Ross, but it was as if he watched another one of his personalities do the killing.

The question, as one psychiatrist put it, was not whether Ross Carlson’s body committed the crime, but which personality was responsible. Psychiatrists for the state called it all an act. The prosecutor argued that Carlson thought he could escape responsibility by feigning his mental condition.

The judge found Carlson incompetent and ordered him confined to the Colorado State Hospital for psychiatric treatment until he was restored to competency for trial. “The ultimate objective was to get him declared insane and treated and committed to a facility that would recognize the validity of his diagnosis,” Savitz says.

According to Savitz, hospital physicians did not believe Carlson had multiple personality disorder and were incapable of treating him properly, but they eventually worked to “fuse” his personalities. Carlson remained in the psych unit for six years before doctors declared him competent.

Savitz says he and Gerash then were faced with the complicated task of mounting an insanity defense for a client whose personalities kept shifting. How could they determine which personality committed the crime? And how could they prove that one personality was insane and others were not? Or could several personalities have conspired to kill his parents?

An unexpected development

Those questions soon became moot. Just months after being released from the state hospital, Carlson was diagnosed with leukemia and was admitted to the hospital under police guard. He resisted chemotherapy treatment at first, complaining that he should not be shackled to his bed like an animal. He eventually began treatment but died within three weeks.

Savtiz was crushed. He says he didn’t realize how close he had become with Carlson, and it was like losing a son. “After all those years, the relationship between me and Ross became more intense and extensive,” Savitz says. “He became more reliant on me for dealing with personal issues. It was the kind of relationship where a younger person relies on an older person.”

Carlson was essentially alone when he died; his grandparents lived in Minnesota, and he had no family in Colorado. Most friends stopped communicating with him after his arrest, except a girlfriend who visited as he was dying. Carlson named Savitz as the administrator of his estate and left his personal papers to him. He also asked Savtiz to write a book about his case.

A psychiatrist for the prosecution beat him to it—but from a different perspective. Michael Weissberg, head of the psychiatric department of Colorado State Hospital wrote a highly critical analysis of the case in The First Sin of Ross Michael Carlson. Yet, Weissberg encouraged Savtiz to write his own book.

Savitz says he worked nights and weekends for years, tried to get an agent, but he got discouraged. He eventually submitted a manuscript to the National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers, which had published some of his legal articles. NACDL released the book fall 2021.

Multiple personality disorder still debated

The use of multiple personality disorder remains controversial as a criminal defense, as many believe it easily can be faked. The story of “Sybil,” based on a patient named Shirley Mason, was discredited in a 2011 book that revealed Mason admitted to making it up, and her treating physician had capitalized on publicizing the story.

Savitz still believes his client had the disorder, brought on by the abuse he says he endured as a child and teenager, a view he says, that’s supported in the medical literature and by the diagnosis of other respected psychiatrists.

Since that case 30 years ago, Savitz says he has worked with other clients diagnosed with multiple personality disorder in civil matters, as well as with others with mental illness and psychiatric disorders.

Walter Gerash, Savtiz’s co-counsel, recently turned 95 and is living in a memory care facility in Denver, says his son Dan, also a criminal defense lawyer. The younger Gerash recalls how his father was obsessed with the case and became convinced that Carlson suffered abuse as a boy that led to his disorder.

He recalls missing his dad on holidays and special occasions while he was on the case. He remembers saying to his dad, “You’re more concerned about a kid who murdered his parents than your own son.”

And his dad responded, “He doesn’t have any parents.”

“I will never forget Ross Carlson very easily,” Savitz said at a memorial service for his client. “He has imprinted my soul and impacted my life. … I believe that certain cases cry out for a lawyer’s compassion.”