In new admissions cycle, law schools are trying to avoid 'litigation bait' with race-neutral plans

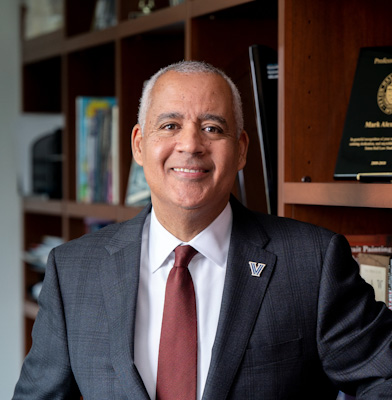

“Every school will be under a microscope about what they are planning to do,” says Mark Alexander, dean of the Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law and president of the Association of American Law Schools. Image from Shutterstock.

After last month’s U.S. Supreme Court opinion that found race-conscious university admissions decisions to be unconstitutional, the clock is ticking for law schools determining what to do when the new applications cycle begins in September.

Chief Justice John Roberts’ majority opinion in Students for Fair Admissions Inc. v. President and Fellows of Harvard College found that if applicants discuss how race affected their lives, including experiences that involve overcoming adversity or discrimination, universities can consider that for admissions purposes. But decisions must be based on the individual student’s experience and perseverance, not their race.

Harvard and the University of North Carolina were parties in the litigation. Both institutions allowed race to be considered in admissions, and the June 29 opinion reverses various landmark opinions on affirmative action in education. It also noted that consideration of race led to a decrease in Asian American admissions, which made race a “negative factor” for the group.

A day after the opinion was published, Stephen Miller, a former adviser in President Donald Trump’s administration and now president of America First Legal, sent letters to 200 law school deans stating that the organization would sue if they allowed “illegal and discriminatory practices to continue.”

Miller did not respond to ABA Journal interview requests.

“Every school will be under a microscope about what they are planning to do,” says Mark Alexander, dean of the Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law and president of the Association of American Law Schools.

“We all know the big picture, but the specifics of implementation are still being determined,” he adds.

Mark Alexander is the dean of the Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law and president of the Association of American Law Schools.

Mark Alexander is the dean of the Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law and president of the Association of American Law Schools.

The Augustinian Catholic university’s motto is “Veritas, Unitas, Caritas.” That means “Truth, Unity and Love,” and admissions policies will be based on the school’s values in a way that complies with the opinion, Alexander says.

“I am hearing people tell admissions offices that ‘whatever you do, you will be sued,” says Peter Lake, a professor at Stetson University College of Law and director of its Center for Excellence in Higher Education Law and Policy.

He refers to the opinion as “litigation bait,” and anticipates hundreds of lawsuits. Lake predicts the Supreme Court will likely leave many decisions to the federal circuits, much like what happened with the 1954 school desegregation case Brown v. Board of Education.

Lake, who is also an attorney with Steptoe & Johnson, thinks universities with religious affiliations may have a good argument to continue using race in admissions decisions.

“What if a religious organization had a sincerely held belief that racism is a sin in America related to slavery, and it is deeply committed to ending discrimination after the Civil War?” Lake asks. “I think this court has made clear it puts a lot of emphasis on religious freedom.”

Others say that could be a risk university general counsels are not willing to take. However, many lawyers interviewed by the ABA Journal do expect writings about race in applicants’ personal statements. During oral arguments in the University of North Carolina case, Justice Amy Coney Barrett asked about a Black applicant submitting an essay that discussed their struggles with racial discrimination, and whether that would be improper for a school to consider. Patrick Strawbridge, who represented Students for Fair Admissions, said no.

Some state universities, including those in California, are already prohibited from using race in public university admissions. Kristin Theis-Alvarez, the assistant dean of admissions and financial aid at the University of California at Berkeley School of Law, estimates that a third of the applicant pool discusses their race or ethnicity in narrative statements.

“Almost always this is raised in relation to a broader discussion of points of intersection between their racial and ethnic identity, their lived experience, and their interest in law school or specific career goal,” she told the ABA Journal in an email.

According to Berkeley Law’s most recent 509 Report, it has a total of 1,019 students. Of that group, approximately 45% are white, 17% are Asian, 15% are Hispanic or Latino, 9% are multiracial, 6% are Black and 0.3% are Native American.

At universities where race was allowed as a consideration, admissions offices may be looking at applicants’ personal statement questions to find ways to learn about their individual circumstances without soliciting information about race, says Jeffrey Nolan. A Holland & Knight partner, he adds that until the U.S. Department of Education releases expected guidance for the opinion, universities can look to a White House fact sheet. The June 29 communication includes a request from President Joe Biden asking schools to give “serious consideration” to adversities qualified applicants have overcome. That could include their families’ financial means; discrimination hardships, including racial discrimination; and where they were raised, the release states.

Nolan does not think such considerations would lead to admitting more students of color than a system that sees race as a plus factor. He adds that universities should be “very thoughtful” in documenting their rationale for changes made in light of the decision, because the planning records could be discoverable in litigation.

Meanwhile, the Law School Admission Council is working on a research project that helps law schools evaluate whether a candidate had an environment where it was hard to thrive academically, says Kellye Testy, president and CEO of the LSAC. The work is being done with the College Board, which oversees the high school Advanced Placement program and the SAT.

And currently, the LSAC through FlexApp offers schools race-neutral questions for the application process, such as whether a student received any Pell Grants while in college or whether a student is a first-generation college graduate.

“Our counsel has been you need more information [from applicants], not less, and make sure you have consistency among the people who review the files,” Testy says.

See also:

ABAJournal.com: “SCOTUS strikes down race-conscious admissions programs at Harvard, University of North Carolina”

Write a letter to the editor, share a story tip or update, or report an error.