From feeling shame to inspiring hope, Steve Price was just getting started

Steve Price died at age 57. Photo by Wayne Slezak.

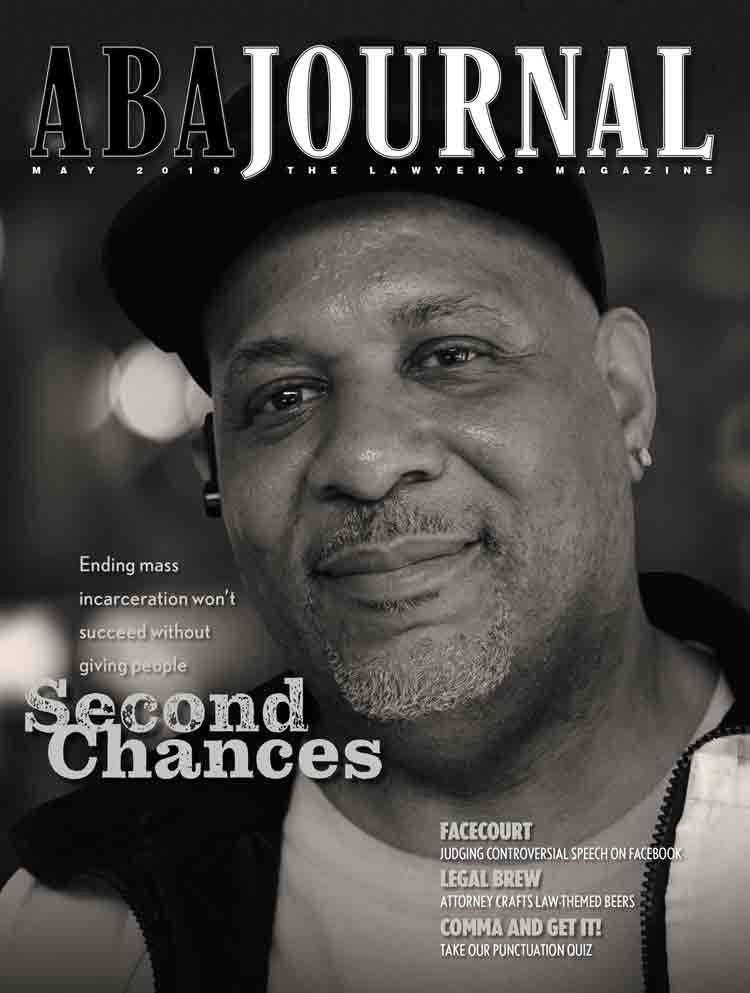

This past spring, when the May 2019 issue of the ABA Journal arrived from the printer, I made plans to meet with Steve Price, whose face graced the cover. I wanted to hand-deliver a few copies and say thanks. Steve was a formerly incarcerated man who talked with me about his struggles to make it on the outside.

Steve didn’t know he was on the cover. I wanted to surprise him and two other men who helped get Steve back on his feet at a community reentry organization on the South Side of Chicago where Steve now worked. When I showed Steve the magazine, his face beamed and his eyes welled up with tears. “Oh, man,” he said, shaking his head in disbelief. “I never thought I’d be on the cover of a magazine. I’m going to have to show this to all my family and friends. I just can’t believe it.”

Steve had shared his story with me for an article I wrote examining the many challenges formerly incarcerated people face on the outside. Steve was like many others, mostly African American men, who cycle through the prison system and never really get the second chances they need to succeed. Because of their criminal records, they face an array of collateral consequences that create barriers to getting a job, finding housing and building a new life.

The cover photo of Steve shows a man with hope in his eyes and a sense of contentment that eluded him for so many years. He had much to be thankful for after years of struggling with addiction and multiple trips to prison. He told me how he wanted to work with young people to be the mentor he never had. We texted and talked a few times after the story came out, and then I lost touch for a few months. Several times I told myself I should call him to say hello and see how he was doing.

One night a couple of weeks ago, I got a text from Joshua Coakley, the reentry director and program manager for violence prevention at Target Area DevCorp., the organization that hired Steve after prison. He wanted to know if I could talk by phone. My heart raced. I just knew it was about Steve. My fear was that he was in trouble again, maybe had a relapse.

Steve Price (top center) as a young man with his family. Steve was raised by a single mother in the Auburn Gresham neighborhood of Chicago.

Steve Price (top center) as a young man with his family. Steve was raised by a single mother in the Auburn Gresham neighborhood of Chicago.Coakley told me Steve had died. He collapsed while getting ready to drive to work. According to the medical examiner’s office, he died from hypertension and cardiovascular disease—natural causes. His hard life in prison and on the streets of Chicago no doubt took a toll. He had told me that while in prison he had developed blood clots in his legs and had a liver transplant. He was only 57 when he died.

It was hard to believe Steve was dead. He always seemed well and in good spirits when I went to see him in the Auburn Gresham neighborhood where he grew up. He had talked with me about being raised there by a single mom, about joining a gang to feel accepted, about getting hooked on drugs and going in and out of prison most of his adult life. I once halted our interview as he quietly wept while telling me of the shame he felt when admitting to other inmates that he didn’t know how to read.

The man who told me these stories, this big, gentle-voiced person with warm inviting eyes and a friendly personality seemed far removed from those days. He tried to use his time in prison wisely to build himself up into a better man. He learned to read. He earned a GED and a barber’s license. He kept trying to do the right thing. But he found once he got released, no one wanted to hire him, and he slipped back into his old ways. It wasn’t until he was released at age 56 that Steve found his real second chance through Target Area DevCorp, which provides counseling and job readiness programs. Target Area eventually hired Steve as a violence interrupter. His role was to foster community relations and counsel young people, especially when gang violence flared up.

“This has hit us all very hard,” Coakley, who is also a licensed minister, told me after Steve died. “We were about to promote him.” Steve was going to be an organizer and had just completed outside training as a restorative justice coordinator, Coakley said.

Steve Price (center) was employed by Target Area DevCorp. as a violence interrupter, and had just completed training as a restorative justice coordinator. Joshua Coakley (left) and Steve Perkins worked with Steve at Target Area DevCorp. Photo by Kevin Davis.

Earlier this month, I went to Steve’s funeral at the Ambassadors for Christ Church, just around the corner from where he worked at 79th and Ashland. His friends, family members and colleagues spoke of Steve’s transformation, about his warmth, about how excited and proud he was to have created a new chapter in his life. There was jubilant singing, spontaneous shouts praising the Lord and a message from the pastor that it’s never too late to change.

Steve had only just begun helping others avoid the mistakes he made as a young man. He told me that he was so happy his mom saw him succeed just before she died last year. He was feeling good about himself because he refused to allow the stigma of having a criminal record define him. Steve’s legacy won’t be his criminal record, but what he did to get past it. The hope and pride on his face will always grace the cover of the ABA Journal and remain in the memories of those whose lives he touched.