Prosecutor reveals in interview how he helped clear Richard Jewell’s name in Olympic bombing investigation

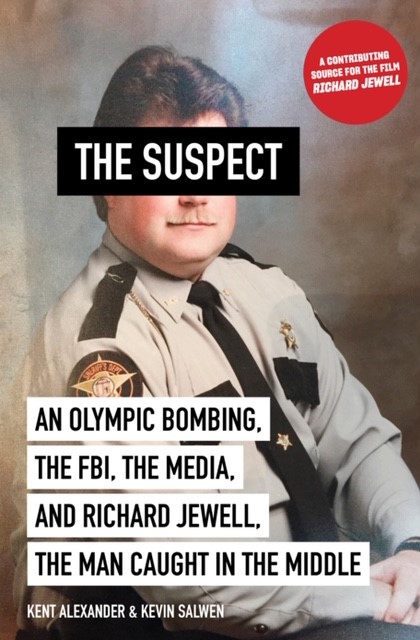

Kent Alexander.

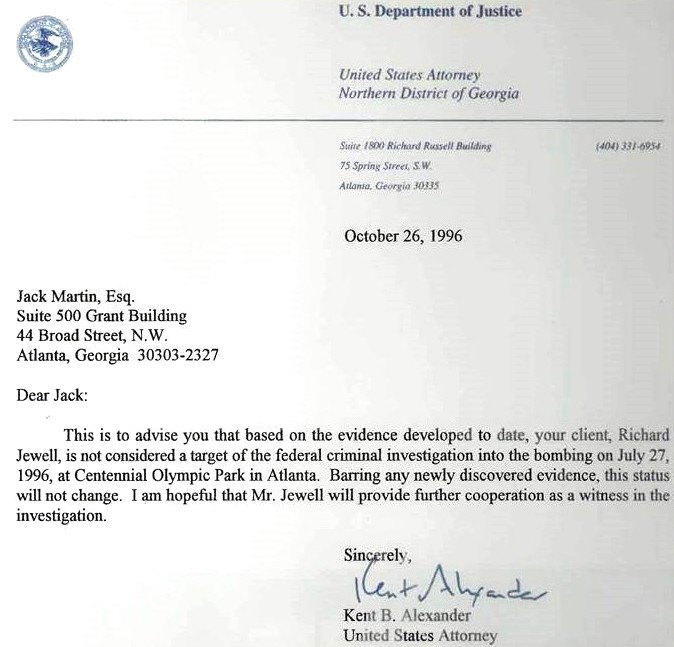

Kent Alexander called it “the most difficult letter to write in my career,” explaining that it took days, and he recast it dozens of times. Curiously, when he finished, the United States attorney for the Northern District of Georgia signed his name below just three sentences.

Alexander’s succinct but painstaking correspondence was penned to Richard Jewell’s lawyer, informing him that his client was not considered a target of the criminal investigation of the bombing at the 1996 Olympics in Atlanta.

Jewell was an unemployed small-town cop working as a security guard at Centennial Olympic Park. In the early hours of July 27, 1996, he spotted a suspicious backpack under a bench in the crowded park. Jewell acted quickly, and with the help of a Georgia Bureau of Investigation agent, cleared the crowd away from the explosive device. Ten minutes later, it detonated and two people died. But Jewell’s actions unquestionably saved scores of lives.

Jewell was proclaimed a hero. CNN, USA Today and television’s Today came calling. But then law enforcement turned the tables and began to suspect Jewell as the bomber. His name was leaked to the Atlanta Journal-Constitution as a suspect. Three days later the hometown paper’s front-page headline screamed: “FBI suspects ‘hero’ guard may have planted bomb.” Boom, just like that, Jewell was reviled by the media, shredded by late-night comics and all but convicted in the eyes of the public. Alexander, following a massive FBI investigation, cleared him three months later. But Jewell’s old life was never coming back.

As the feds’ top lawyer in Atlanta, Alexander was in the middle of it all. “After the bombing, the FBI became my second home,” he tells me in an interview by phone. “All of us were singularly focused on finding the terrorist before he struck again.”

Alexander’s behind the scenes account of Jewell’s story is told in The Suspect, co-authored with former Wall Street Journal editor Kevin Salwen, who oversaw the paper’s coverage of the bombing. The authors also take readers inside law enforcement’s seven-year search for the real bomber, Eric Rudolph, who pled guilty to the Olympic bombing and three subsequent ones. Rudolph is serving life in prison.

“I knew I was going to write this book a week-and-a-half after I wrote Richard Jewell’s clearance letter,” Alexander, 61, says. “It was a great story, and I wanted to figure out what really happened.”

He also wanted to examine what lessons could be learned from an experience that ruined an innocent man’s life. For that, Alexander’s 20-plus year delay, in keeping his promise to himself, proved handy. “Much of what happened in 1996 applies even more today. Now it’s so easy for the ‘Jewell effect’ to happen on any given day,” Alexander says.

At the end of last year, a month after the book’s release, the Clint Eastwood-directed film Richard Jewell hit theaters. As a full-screen credit declares, the cinematic version of the hero-turned-villain’s story is based on Alexander and Salwen’s work.

It can be a tall task to keep readers’ interest in a book where they know the ending before starting, but Alexander and Salwen figured out how to pull it off—and very well. “The story’s key players were so strong and colorful and had such interesting backgrounds, we realized early on that writing a character-driven book was the way to go,” Alexander says.

Of course, there is Jewell—an underachieving cop with law enforcement aspirations that he will never attain. Jewell is cash-strapped, has few friends, lives with his mother and has no romantic life, according to the book. So, when his life-saving act turns to talk of the death penalty, it becomes easy to cheer for his vindication from the government and settlement of several defamation suits.

Playing the part of the media run amok is Kathy Scruggs, described in the book as the provocative, edgy and unrelenting Atlanta Journal-Constitution crime reporter who got the tip about Jewell. There were serious questions within the AJC about whether to run the story naming Jewell as a suspect, according to the book. But there were 15,000 journalists from around the world in town covering the games. Describing the pressure to publish it, Alexander and Salwen write: “Scruggs feared the worst: One of the carpetbagger journalists in for the Olympics would break the news in her town and on her beat.”

Alexander and Salwen demonstrate that the government’s downfall was relying on an FBI-created psychological profile that led to Jewell becoming the suspect. That got former FBI agent Don Johnson to sink his teeth into Jewell and not let go, despite a lack of evidence, the authors write. Johnson also got into hot water when it was determined that he was less than clear with Jewell about the purpose of a Miranda warning during an initial interview, according to the book.

A massive FBI effort put every crumb of Jewell’s life under a microscope. Agents conducted an all-day search of every nook and cranny of his mother’s apartment and removed troves of possessions, according to the book. They interviewed Jewell for nearly six hours. Despite all this, investigators uncovered no evidence that Jewell was the bomber. It was time for Alexander to announce that the government’s attack was over.

Kent Alexander’s 1996 letter.

Kent Alexander’s 1996 letter.

The challenge in writing the letter, Alexander explains, is that it had to appease different audiences. Richard Jewell expected full clearance, but instead was described as a so-called “non-target.” Nonetheless, Jewell and his legal team knew the media would portray that as an exoneration. On the other hand, Alexander says, there were some in law enforcement who still thought that Jewell was the bomber or complicit in some way. “So, the FBI was satisfied because it was not necessarily a clearance letter,” he says. “Deciding how to write that letter really took some thought,” Alexander tells me. “Every single word in there was deliberate.”

Alexander says the Richard Jewell case offers an opportunity for law enforcement and the media to step back and consider: “How fast do we need the news, when does the suspect’s name need to be outed, and what kind of effect does a rush to judgment have on an individual?” He points to similar cases, such as the Duke University lacrosse players falsely accused of rape in 2006 and Sunil Tripathi, the Brown University student wrongly suspected of being the 2013 Boston Marathon bomber.

I tell Alexander that I’m skeptical that this lesson can ever be learned. Thanks to the internet, I offer, we have more journalists than ever. Some legitimate and some whose newsroom is their parents’ basement. But all of them have the same goal: get the story first.

Alexander says he’s not expecting “wholesale change, ‘oh the world’s going to slow down and everybody’s now going to be much more careful.’ ” But, he says, “If you can put a name on an issue, and Richard Jewell is very much a name,” it may cause people to pause. If someone is starting to leak a name of a suspect, they may say, “ ‘Remember Richard Jewell.’ ”

In addition to selling the book rights to Hollywood, the co-authors served as consultants on the film. It brought some memorable moments, Alexander tells me. During a meeting with the film’s producer, Alexander and Salwen were asked if they had “time to meet with Clint Eastwood next weekend.” Alexander, laughing, tells me that he pulled out his iPhone. “I don’t know, let me check,” he replied.

“The whole thing was a ‘pinch-me’ experience,” Alexander says. “How could you be anything but awed in Clint Eastwood’s presence?” But besides making his day, Alexander says he was “very impressed with how sharp he was and with how much he was really directing this movie. It wasn’t like anyone was propping [89-year-old] Clint Eastwood up. He was engaged and in charge.”

Alexander offers an entertaining side-note. At the time, Nancy Grace, the well-known legal commentator, was a 36-year-old assistant district attorney in Atlanta. She appeared on Good Morning America to give her two cents on the case. Blunt and accusatory, Grace speculated that Jewell’s arrest was imminent. She even denied that Jewell enjoyed a presumption of innocence since there was no jury trial on-going, Alexander recalls.

After a near all-nighter at the FBI, Alexander says he was awoken by an early-morning call from Washington. A loud and fast-talking Deputy Attorney General had a simple directive: “That woman is the face of justice. Get her off of there.” Alexander called Atlanta’s D.A. and he promised to take care of it.

But while Alexander achieved the unimaginable—putting a gag order on Nancy Grace—he may have also played a part in launching her second career. A short time later, Grace resigned from the prosecutor’s office and joined Court TV as a commentator. “It was clear to me going forward” Alexander says, “that Nancy aspired for a future in the media, not the D.A.’s office.”

Alexander has sat behind a variety of desks since graduating from the University of Virginia Law School in 1983. He jokingly described his career as “professionally unfocused.” The Atlanta native, in addition to over 10 years in the U.S. Attorney’s office, has made stops at King & Spalding as a partner, Emory University and its healthcare system as senior V.P. and general counsel and served as GC for international humanitarian organization CARE. Alexander also put a toe into politics as chief of staff for Michelle Nunn’s 2014 unsuccessful campaign for a U.S. Senate seat from Georgia. Alexander is currently working on his next book, a narrative nonfiction story that runs from the 1980 Cuban Mariel boat lift to the 1987 “Marielito” Atlanta Penitentiary riot and takeover.

Randy Maniloff.

Randy Maniloff.

Alexander and Jewell ran into each other at the Atlanta courthouse where they had both come to watch Eric Rudolph plead guilty to the Olympic bombing. It had been nearly nine years since the former U.S. attorney had written the letter that cleared the falsely accused security guard.

Alexander reached out to shake hands. Jewell surprised him with a hug. The former prosecutor thanked him again for what he did at the Olympics and told him that this day was a long time coming.

“In the end, of course, he was no bomber at all. He was a hero.”

Jewell died in 2007 at the age of 44 of complications from diabetes.

Randy Maniloff is an attorney at White and Williams in Philadelphia and an adjunct professor at Temple University Beasley School of Law. He runs the website CoverageOpinions.info.

Write a letter to the editor, share a story tip or update, or report an error.