Former US Rep. Trey Gowdy on being a prosecutor: 'That's the job I want to be known for'

Trey Gowdy in 2016. Photo from Wikimedia Commons.

Trey Gowdy tells me that if I came to his home office in Spartanburg, South Carolina, I would never know he had been a member of Congress.

“There is not a single sign [of it] anywhere in my house or in my office at the law firm,” he says.

Notwithstanding his lack of congressional bric-a-brac, Gowdy’s eight years in the House of Representatives is why most people know him. But that is not his preference. Gowdy was once a prosecutor.

“That’s the job I want to be known for,” he emphatically says during a phone interview from that home office.

Gowdy did the job, which he says had “the highest sense of purpose,” for six years as an assistant U.S. attorney, followed by 10 as a solicitor (district attorney) in the Palmetto State. Gowdy’s substantial time in the courtroom taught him a lot about the art of persuasion. He remains wildly passionate about the subject.

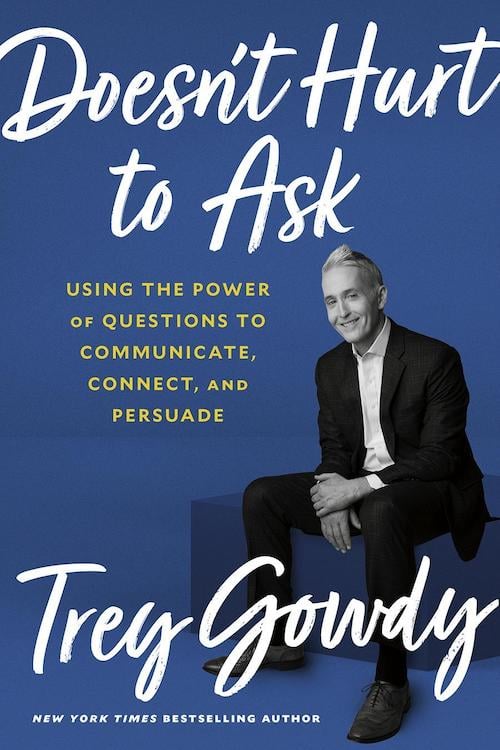

Late last month, Gowdy, 56, published Doesn’t Hurt to Ask. The former prosecutor and congressman applies the lessons he learned on those stages to achieve the book’s subtitle: Using the Power of Questions to Communicate, Connect, and Persuade. It debuted at No. 1 on the New York Times’ bestsellers list in the advice, how-to and miscellaneous category.

In his book, Gowdy shares his views on persuasion in a host of environments, such as the kitchen table, boss’s office and courtroom. While teaching lawyers is not the mission of his new title—and Gowdy modestly downplays his ability to do so—he in fact has much to offer those who make their living standing before juries.

Gowdy is quick to point out that when it comes to persuasion, there is a world of difference between courtrooms and congressional hearing rooms. To be able to serve, he says, jurors must acknowledge that they are open-minded. But “members of Congress, at least in the modern political environment, either cannot be persuaded or cannot admit that they were.”

Such frustration was behind Gowdy’s decision to pack up his office in Washington, D.C. Of his time there, he tells me, “I hated it.”

The recovering politician is currently a partner at Nelson, Mullins, Riley & Scarborough in the firm’s Greenville, South Carolina, office. He devotes half his time to the firm, principally focusing on white-collar investigations and “quasi-prosecutions”—attempting to resolve criminal matters at various stages in the process.

Gowdy misses the courtroom, which he calls his “single most peaceful and comfortable place.” When a colleague recently called to ask a question about a litigation matter, he invited himself onto her trial team. “She didn’t want me. But I just love it. I would rather do criminal work more than anything in the world,” he says.

But the time isn’t right for Gowdy to be conducting voir dire. After a quarter century in public service, he’s taking the opportunity to focus on financing his children’s education through public speaking engagements, media appearances and promoting his book.

“Two years from now, nobody is going to want me to make a speech,” he acknowledges. “And two years from now, I doubt anyone is going to want me to be on television.” Gowdy is a Fox News contributor.

A trial practice is simply not possible for Gowdy while this opportunity exists: “When a judge says we are going to try this case in October, he or she is just not interested in the fact that I committed to speak to some insurance agents in Las Vegas.”

Harold Watson “Trey” Gowdy III graduated from the University of South Carolina School of Law in 1989. Clerkships for judges on the South Carolina Court of Appeals and District Court of South Carolina followed. Then began his first stint at Nelson Mullins.

But private practice was short-lived. Less than two years later, Gowdy landed his dream job—assistant U.S. attorney. He was on the federal payroll for six years. In 2000, Gowdy was elected solicitor for South Carolina’s 7th Judicial Circuit.

Going from being a federal to a state prosecutor seems like a step backward, I suggest to Gowdy. There is precedent for it in South Carolina, he tells me, including two instances in which even the U.S. attorney chose to go from being head of a federal law enforcement office to overseeing a state one.

Gowdy made the move, he explains, to achieve variety in his work.

“Once you’ve done a couple of narcotics cases, you’ve done them all,” he says, describing his time as an AUSA. The same goes for firearms cases.

“A federal prosecutor,” Gowdy says, “is like being a research scientist that specializes in one point on a chromosome or gene. And you’re just really, really, really, good at that.” But a state prosecutor is “like being an emergency room physician. You just take whatever comes in.”

A 2016 Rolling Stone profile gave Gowdy plaudits for his talents in the courtroom, calling him Atticus Finch. And then adding—in pink seersucker. About that sartorial choice, Gowdy tells me it was a gift from homicide detectives in the Spartanburg County sheriff’s office. And one he treasures.

“Cops don’t make a ton of money,” he says. “So for them to go pool their money and have a suit made—not bought, but made—for a prosecutor, you’re doggone right I’m gonna wear it. No matter how ridiculous I look in it.”

Gowdy credits one technique for his success to thinking like a defense attorney—something he says some prosecutors “will not or cannot” do: “You have to think like a skeptic. … You have to say, ‘OK, great; you got the fingerprints, but that’s not enough.’” Of his trial preparation: “I lived in fear that somebody was not going to believe my best pieces of evidence.”

Despite his love for the job, Gowdy stepped away after 10 years.

“It takes its toll on your soul,” he says. “There are no trials for good, decent or kind people in the courtroom; the trials are for those who murder, rape and commit burglaries. … When evil is all you see, you fall prey to believing it is all that exists.”

Gowdy left the courtroom because “the questions were better than the answers.” He could never answer why, from a theological standpoint, such depravity exists.

In 2010, the lifelong Republican was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives from South Carolina’s 4th Congressional District. His service included chairing such high-profile committees as House Oversight and Government Reform and the Select Committee on Events Surrounding the 2012 Terrorist Attack in Benghazi. After eight years, Gowdy left Congress, where, he says, “the questions never mattered,” referring to the fact that “almost everyone in Washington, D.C., already has his or her mind made up.”

The idea for Doesn’t Hurt to Ask came from Gowdy’s close friend, Republican South Carolina Sen. Tim Scott. “‘I want you to show people,’ Scott said, ‘how what you learned in a courtroom can help them in real life.’” But Gowdy was skeptical. “I could write a haiku,” he told Scott. “I could write a sonnet. I can’t write a book on that.” The senator told him to try.

One of Gowdy’s theses is that persuasion is not achieved by arguing. It is more subtle. He suggests using questions to persuade. Make the other side see things they hadn’t otherwise. Essentially, get people to persuade themselves.

On the subject of trial lawyers and the art of persuasion, Gowdy places much emphasis on the need for authenticity. “When I got to the DA’s office, I was stunned at the number of seasoned prosecutors who, in their opening argument, asked for a verdict,” Gowdy says. “That’s the craziest thing I ever heard in my life. How in the world can you possibly do that?” After all, “the judge just got through telling them you can’t even begin to make up your mind until a couple of days from now.”

Rather, Gowdy says the purpose of opening argument is simply to lay out the “table of contents” for the jury. “When you sit down, you want the jury to think, ‘That young woman or that young man won’t lie to me.’ That’s it.”

Achieving authenticity also includes what Gowdy calls, oddly, “faking sincerity”—a concept he learned from David Stephens, a recently retired federal prosecutor in South Carolina whom Gowdy calls the best trial lawyer he has ever seen. The student of the technique calls it “the single best advice you will ever get about effective communication and the hardest to perfect.”

Of course, you cannot fake sincerity. By this, he means that a trial lawyer finds a reason to be passionate about what is otherwise a mundane case. Gowdy goes back to Stephens for an example, explaining that it was hard for him to get passionate about just another drug case with no identifiable victim.

Instead, Stephens talked about an “evil wind sweeping across the playgrounds and schoolyards of America, gathering lives in its wake.” Gowdy calls this something Stephens “could be passionate and therefore sincere and authentic about.”

Gowdy also stresses the need for trial lawyers to be able to change course midstream. “A mistake that I see lawyers make is they become so wed to their theory of the case that they are almost incapable of pivoting.” Gowdy explains that “it doesn’t matter how compelling you think that piece of evidence is.” A lawyer must be able to recognize whether it has “resonated in the room,” and if not, be able to pivot.

At bottom, Gowdy says to be persuasive, you must demonstrate that you are yourself persuadable.

“It is a huge turnoff when you tell people, ‘I am going to try to change your position on gun control, but I myself am not open to it.’” Gowdy is animated on this point: “I can’t think of anything less conducive to moving someone than to admit to them up front that you are unwilling to do the very thing that you are asking them to do.”

Gowdy calls himself persuadable.

“I am one fact away from changing my view. But it has to be a true fact,” he says.

Randy Maniloff is a lawyer at White and Williams in Philadelphia and an adjunct professor at the Temple University Beasley School of Law. He runs the website CoverageOpinions.info.

Write a letter to the editor, share a story tip or update, or report an error.