Deb Haaland, other Native American 'first trailblazers' discuss importance of being at the table

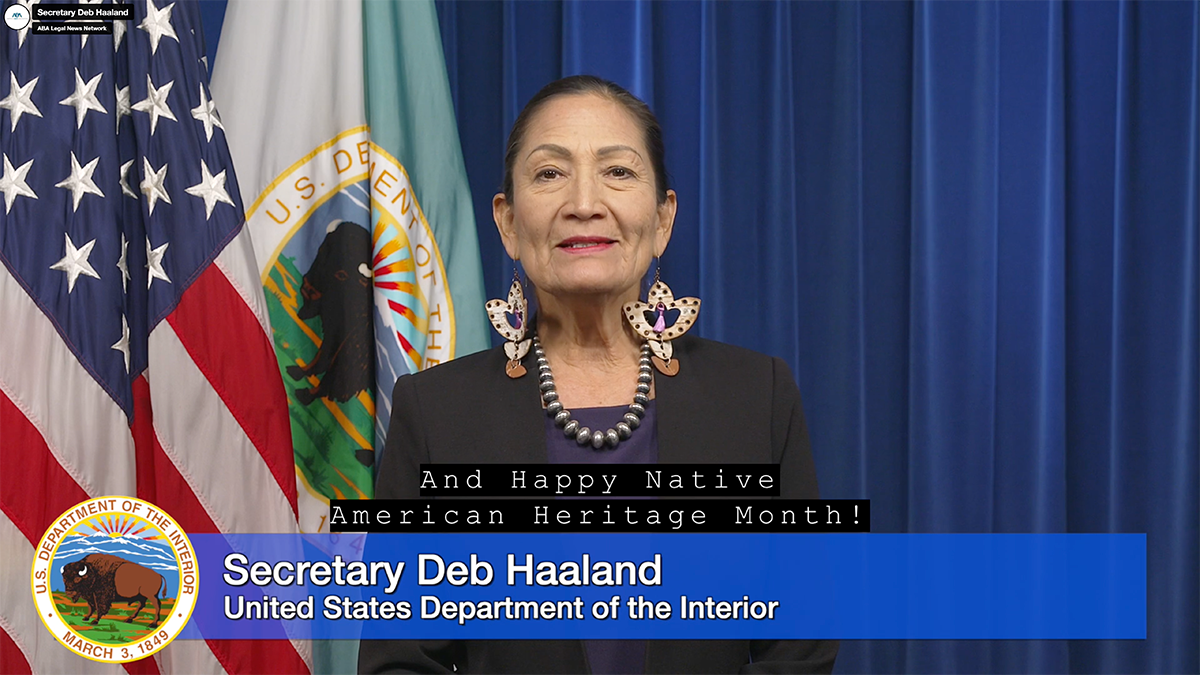

U.S. Secretary of the Department of the Interior Deb Haaland spoke as part of the ABA Presidential Speaker Series.

With the celebration of Native American Heritage Month in November comes a stark reminder that for too long, Indigenous people have been pushed to the margins of society, U.S. Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland said in special remarks made to the ABA on Thursday.

But that is changing, added Haaland, a member of the Pueblo of Laguna and a 35th generation New Mexican who became the first Native American to serve as a cabinet secretary. She introduced the latest installment in the ABA Presidential Speaker Series, a collection of virtual discussions exploring the personal and professional journeys of world leaders, philanthropists and other change-making guests.

“Indigenous people and Indigenous knowledge are at the decision-making tables,” Haaland said. “Our representation is tangible, and we aren’t going back. We are breaking down barriers, so that our communities have the representation they deserve everywhere—in statehouses, in Congress, in classrooms, in film, science and right here, with the American Bar Association.”

Following Haaland’s remarks, Makalika Naholowa’a, executive director of the Native Hawaiian Legal Corp. and the first Native Hawaiian president of the National Native American Bar Association, spoke with a panel of other Native American female “first trailblazers” about their journeys through the legal profession and how they are now supporting young Native American lawyers and law students.

The full video can be viewed here.

Stacy Leeds, a member of the Cherokee Nation and the dean of the Sandra Day O’Connor College of Law at Arizona State University, said in her experience, Native American students who find themselves alone or part of only a small group of others who look like them need help finding their place in the community.

“For those that are on the call that don’t have a lot of Native people working in their organizations, center that consciousness that people are always looking for community and figure out ways to help connect,” said Leeds, the first Native American woman to serve as a law school dean. “That belonging piece and that having a path of people that you’re walking along with is so critically important to success.”

Chief Judge Abby Abinanti of the Yurok Tribe—who was the first Native American woman to pass the California bar exam—explained she and her colleagues needed to get creative, both to better serve their community members and to expand the capacity of their court.

“When we started the court here, we had three people,” Abinanti said. “Now we have 60, and a lot of them are in the field working. And what is their role? We call them advocates, but we train them to be aunts and uncles. … It’s a different way of doing it, but we need those people.”

Kimberly Teehee, the first delegate-designate to the U.S. House of Representatives from the Cherokee Nation, agreed that representation matters. She pointed out that when she started her career, more non-Native Americans than Native Americans practiced federal Indian law.

Teehee said when she mentors young people, and young women in particular, she tells them their generation is going to be more competitive than hers, but it will hopefully encounter fewer obstacles.

“Their generation is going to have a lot more opportunities because more glass ceilings have been shattered for our community,” said Teehee, who also served as a former senior policy adviser for Native American affairs in the White House. “Whether it’s going to be a judge or a cabinet secretary or other things, my hope is that we continue to provide that pathway.”

The panel discussion included (clockwise from top left): Makalika Naholowa’a, Stacy Leeds, Kimberly Teehee, Chief Judge Abby Abinanti and Valerie Nurr’araluk Davidson.

The panel discussion included (clockwise from top left): Makalika Naholowa’a, Stacy Leeds, Kimberly Teehee, Chief Judge Abby Abinanti and Valerie Nurr’araluk Davidson.Teehee and Valerie Nurr’araluk Davidson, the first female Alaska Native to serve as lieutenant governor of Alaska, both highlighted the importance of not “pigeonholing” Native Americans into positions solely involving Indian or tribal law.

“As Native people, we have been long been told of what we should be and what we should do,” said Nurr’araluk Davidson, who is Yup’ik and now the president and CEO of the Alaska Native Tribal Health Consortium. “I think what we want to do and what we want to be is whatever the heck we want to be.

“And so, if you’re a person who wants to do private practice, if you want to be a judge, if you want to use your legal background to promote other students getting into law or you decide that you know, law is a really interesting, wonderful background to have to help advance policy, that’s a good thing.”

‘Be the person in the room’

Naholowa’a and the panel also discussed how other attorneys and organizations like the ABA can assist with efforts to advance young Native American lawyers.

Leeds encouraged more experienced attorneys to be deliberate about knowing younger attorneys and including them in opportunities for assignments.

“We can think of situations in our own workplace where you’re having some strategy session, and someone says, ‘You know, we really need somebody who can take on X project,’” Leeds says. “Be the person in the room that says, ‘Well, what about this person?’

“I think oftentimes the biases in the workplace are not overt, they are just that certain people don’t naturally cycle to the top of your head when you’re thinking about somebody to make an assignment to.”

Teehee said the ABA can also make a significant difference for Native American lawyers by educating the public and decision-makers about the importance of tribal court experience.

“There is a great need for ABA to help lift the veil of mystery of what tribal experience means in this country,” Teehee said. “I do recall having to take part of these kinds of conversations when I worked within the White House and worked with the judicial nominating committee … fighting for tribal court experience to be treated equally as other types of experience and making sure that contributed to the diversity on the bench in the federal system.

“That’s a conversation that is still going on today and that’s one the ABA can absolutely assist with.”

On Thursday, the ABA Commission on Women in the Profession and National Native American Bar Association released Excluded & Alone: Examining the Experiences of Native American Women in the Law and a Path Towards Equity, a new report based on a qualitative research study of the unique experiences of Native American women who are navigating the intersection of race and gender in the legal profession.

Commission on Women in the Profession member Jin Hwang and past National Native American Bar Association President Linda Benally, who served as the study’s co-chairs, presented the key findings after the panel discussion.

For complete study results and other information, visit the ABA Commission on Women in the Profession’s website.

For more information about the panel discussion and other past and upcoming programs, visit the ABA Presidential Speaker Series website.

Write a letter to the editor, share a story tip or update, or report an error.