'Death by Cop': A judge joins the brother of a Black man killed by police to promote racial healing

Officer Scott Smith from New Milford, Connecticut, shot and killed Franklyn Reid in 1998. Photo from AP Images.

On a cold December morning in the town of New Milford, Connecticut, Officer Scott Smith was driving an unmarked police car along Route 202 looking for Franklyn Reid, who was wanted on some warrants. Smith, who is white, spotted Franklyn, who is Black, near a gas station.

Smith, in plain clothes, stopped the car, jumped out and yelled, “Police! Police! Stop, Franklyn!”

Franklyn darted off. Smith, who was among several officers searching for Franklyn that morning, ran after him. As Smith got closer, Franklyn stopped, turned his head and looked at the officer. Smith, unholstered his gun. “Show me your hands! Show me your hands!”

The officer moved in and got Franklyn down on the ground.

Smith’s account of what happened next would differ from what others nearby said they saw on that day back in 1998. But this much was certain: Smith shot Franklyn in the back at close range, killing him.

Smith said he thought Franklyn was reaching for a weapon and feared for his life. Franklyn, it turned out, was not armed, though a small pocketknife was found in a jacket nearby.

After the shooting, folks around New Milford, population about 27,000, began talking. Some believed it was racially motivated and demanded the officer be held accountable. There were small protests in the mostly white community, which remained peaceful. Social media platforms such as Twitter and Facebook did not yet exist to spread the news or ignite the kind of unrest that has erupted in recent months after police shootings of Black people.

Three weeks after Franklyn was killed, the state brought murder charges against Smith, making him the first Connecticut police officer charged with murder for an on-duty shooting. Smith had been on the force for just two years.

Wayne Reid, Franklyn Reid’s younger brother.

Wayne Reid, Franklyn Reid’s younger brother.

Franklyn’s younger brother, Wayne Reid, sat through a grueling and emotional three-week trial with his parents, Jamaican immigrants who were crushed by the experience. A jury convicted Smith of the lesser charge of first-degree intentional manslaughter, and the judge sentenced him to six years in prison.

But story didn’t end there.

A journey to understand

In the years that followed, Reid developed an unlikely friendship with Charles Gill, the Litchfield District Superior Court judge who presided over the trial. Reid had wanted to write a book about the case. He was motivated not to be divisive or anti-police, but instead driven to take a deeper look at the case and promote racial healing. Reid approached Gill to ask whether he’d be interested in collaborating.

“I said, ‘Judge Gill this is such a dramatic story. We can tell what occurred, but also use it as an opportunity, hopefully, to bring community and law enforcement together,’” says Reid, now an assistant controller for a PR agency in New York City.

Judge Charles Gill.

Judge Charles Gill.

Gill said yes. “This case was very emotional for me,” he says. “Very difficult, as you can imagine.”

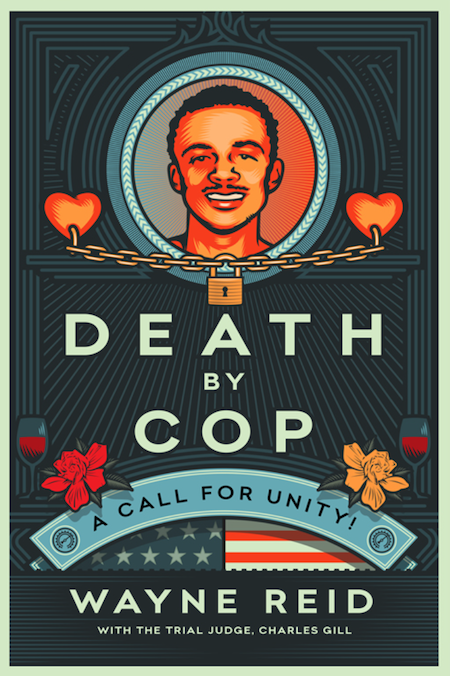

Death by Cop: A Call for Unity!, which they self-published in January, has turned out to be as timely and relevant as ever. The original cover was a color autopsy photo of Franklyn’s body, face down with a gaping bullet hole between his shoulder blades. Reid and Gill are re-releasing the book this month with a new cover that celebrates Franklyn by using a smiling portrait of him and with the hope of renewing interest by using a more positive image.

Reid says he wanted to provide a full account of the circumstances leading up to the shooting and its aftermath, while also describing the human toll it took on so many.

“I would like readers to understand that these tragic incidents traumatize the victims and officers’ families,” he says. “We must show compassion for all involved.”

While it’s uncommon for judges to publicly discuss their cases Gill, now retired, felt compelled to share his thoughts and insights. “Our message is unity from an unlikely source; a victim’s brother and perhaps for the first time in journalism, the trial judge,” he says.

The judge, a national advocate for children’s rights and the co-founder of the nonprofit National Task Force for Children’s Constitutional Rights, also felt there was much to learn.

“This case can be an example for other cases that have gone wrong,” Gill says. “It’s important to get a realistic view, a humanistic view of who police are, what their jobs are, and they should learn how to de-escalate situations rather than jump into them.”

The book is drawn from Reid’s own experiences living through the ordeal, along with thousands of pages of documents, transcripts and statements that were part of a civil case the family filed against the town. (The family settled for $1.6 million.) “I started to go through [the court records], and it gave me a completely different perspective of the case and what occurred,” Reid says.

Writing about it was more difficult than he anticipated. “For the first nine months, I cried every single day and single night, but I persevered through it,” Reid says.

A brother’s grief, a family’s struggle

Wayne Reid was in Fort Lauderdale, Florida, with his teammates from the University of Scranton wrestling team when he got the news on Dec. 29, 1998, that his brother had been shot dead by police.

“I suddenly feel as if I’m asleep in a hollow tunnel, having a terrible nightmare,” he writes. “But I am awake, frozen in time, with the phone at my ear. I can’t decipher the numerous thoughts flooding my mind.”

Following the shooting, there were small rallies in New Milford—rallies supporting Smith and rallies seeking justice for Franklyn—but nothing on the scale of events sparked by more recent police shootings.

“If this incident occurred in 2020 instead of 1998, I think the reaction and response would be vastly different. I think New Milford would have become a hot spot, and we would have been experiencing similar scenes as we have been across the nation,” Reid says.

Reid writes that New Milford police put forth their own narrative early on by releasing information about his brother’s criminal history, suggesting he was a dangerous felon. It’s true that Franklyn was known to police. He served nearly three years in prison for sexual assault and assault. When he was killed, Franklyn was facing two charges of violating probation, six counts of telephone harassment and three charges of failure to appear. During one arrest, he attempted to grab a knife.

“The first thing that came out was his record and some people already had already made up their mind about who this individual was,” Wayne Reid says. His brother, a father of three, was not a monster, Reid says. In the book, he writes: “There is nothing to gain in sugarcoating his history. Some arrests were due to his own poor choices or bad decisions; others were exaggerated to substantiate the artificial labels.”

In a recent interview, Reid says his brother was kind and loving. “Although he experienced numerous challenges in life as a young good-looking black male living in a predominantly white community, I like him to be remembered as someone who cared for others, loved his family, enjoyed drawing, writing poetry and loved God.”

In the book, Reid also humanizes Smith, describing his years growing up in Newtown, Connecticut, with his parents and sister. Smith was a standout high school basketball and baseball player. He came from a hardworking, loving family and as a young man had aspirations to become a police officer and state trooper. Smith and Franklyn Reid were both 27 years old at the time of the fatal shooting.

Murder charge creates division

Three weeks after the shooting, Waterbury State’s Attorney John Connelly, despite pushback from police, brought a murder charge against Smith after an investigation found his life was not in peril. Several witnesses testified; one witness said he saw the officer with his left foot planted on Franklyn’s back before he was shot.

New Milford Police Chief James D. Sweeney said he and his officers were “shaken and very disappointed” by the decision to charge Smith. Fellow officers carried signs of support outside the courthouse.

The trial, which began on March 3, 2000, drew daily demonstrations. Gill, concerned about the publicity, instructed jurors to assemble at a nearby church and walk down an alley, escorted by marshals, to an entrance at the back of the courthouse. During the trial, Smith took the risk of testifying in his own defense, sticking to the story, which he gave in an earlier sworn statement, that he thought Franklyn was going for a weapon.

“I was scared to death,” Smith testified. “I saw things flash before me. I thought of my mother and father and I thought of my sister and how much I was gonna miss them and how much I love them. I fired my gun.”

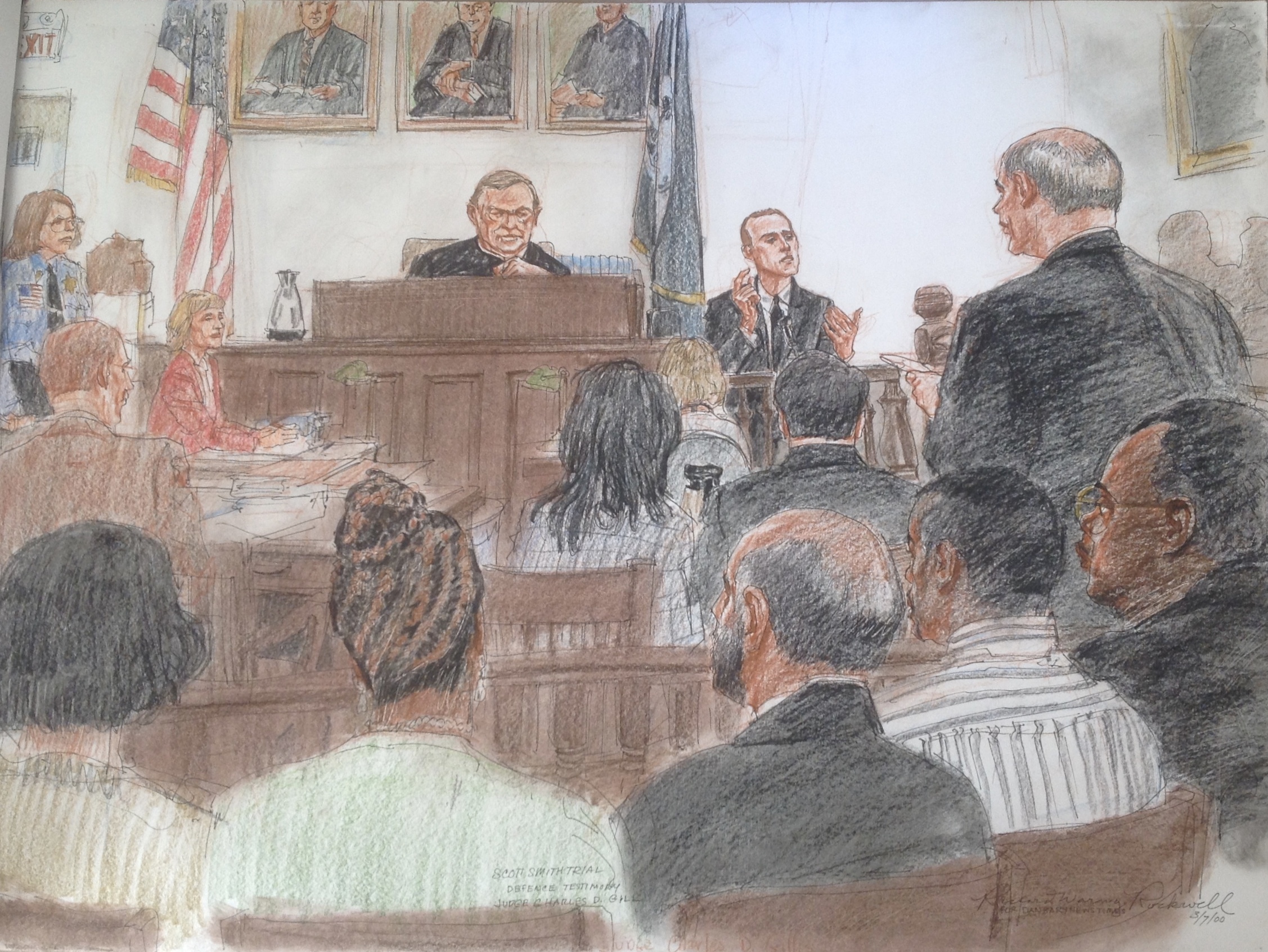

A courtroom sketch from the Smith trial by Richard Waring Rockwell. Courtesy of Judge Charles Gill.

A courtroom sketch from the Smith trial by Richard Waring Rockwell. Courtesy of Judge Charles Gill.

As Smith was testifying, Gill says he thought about the killing of another Black man at the hands of police—a high-profile case that had overshadowed Franklyn’s death. Just two weeks earlier, four New York City police officers were acquitted of killing Amadou Diallo, a 23-year-old unarmed man they shot at 41 times. Gill, who had been following that trial, says he spoke with the presiding judge on that case.

“He told me that all four officers on trial broke down and cried when they testified,” Gill writes in the book. “Their jury found them all not guilty because they admitted they made mistakes and showed sorrow in front of them.”

Both Wayne Reid and Gill were struck by how cold Smith seemed on the stand, showing no regret, remorse or empathy toward the grief-stricken family. They wondered why he didn’t claim it was an accident. They suspected he was coached by other cops to insist Franklyn was a threat.

“In my mind, I said, ‘Cry you son of a bitch,’” Gill says. “He just came across without having any emotions, which is not a good thing to do.”

Witnesses testified that Franklyn did not appear to be resisting arrest, was face down on his stomach and had surrendered. The jury agreed that Smith’s life was not in danger when he shot Franklyn, and it convicted Smith on the first-degree intentional manslaughter charge.

Another death to come

Smith appealed and was allowed to remain free on bail. In October 2002, the state appellate court found that while evidence supported Smith’s conviction, Gill had improperly barred the testimony of two defense experts on police training and the use of deadly force. The court ordered a new trial, noting that the testimony was necessary to determine whether Smith’s use of deadly force was reasonable based on his training and frame of mind.

Gill argues in the book that three experts were unnecessary because the other two would be superfluous.

“It is rare for a trial judge to criticize an appellate court decision that reverses him. But that court clearly earned it in this case,” Gill writes. “According to the law, only one expert witness is required to testify—if the trial judge feels that would be sufficient.”

Rather than face another trial, Smith agreed to plead no contest to a misdemeanor charge of criminally negligent homicide. He also agreed that he would not seek employment as a police officer ever again, which Franklyn’s family insisted upon to accept the deal. Smith was sentenced to a one-year suspended prison term and two years of probation.

Smith never worked in law enforcement again and did some painting and carpentry work. His lawyer said at one time he applied to be a firefighter and was briefly married with one child.

In 2013, Smith was found dead inside a bedroom of his home in Danbury. The state medical examiner ruled his death a suicide, the result of carbon monoxide poisoning after he placed a generator in his room with the windows taped shut. Smith was 41 years old.

“His death is a tragedy, and I’m convinced related to the trial and the tribulations that went along with it,” his former lawyer, John Kelly, told the Hartford Courant.

Wayne Reid felt terrible. “We have a lot of compassion about what happened to Officer Smith and to his family,” he says. “I regret I didn’t get the opportunity to speak with Officer Smith after our legal journey ended in 2004. If I did, maybe we could have shared our emotional feelings and perhaps he would still be alive today.”

The Rev. Cornell Lewis, an activist who organized demonstrations in support of Smith’s prosecution, still believes the shooting had its roots in a racial bias against Franklyn, who had a reputation among police for being trouble.

“I think they demonized him, and it was a small leap from verbal demonization to carrying it out,” Lewis says.

Lewis believes Smith had many options other than to shoot Franklyn. “Historically, I saw a bigger picture. I saw historically what happens to Black and brown people. The fact that he shot him like that indicates to me that it was deliberate.”

A picture of Franklyn Reid in 1998.

A picture of Franklyn Reid in 1998.

Police shootings now and then

Since the trial, prosecutor John Connelly has died. James Sweeney, the New Milford police chief at the time of the shooting, and Colin D. McCormack, chief during the trial, have both retired. Gill, who retired in 2017 after 34 years on the bench, bought a sketch of the Smith trial from the courtroom artist, the late Richard Waring Rockwell, Norman Rockwell’s nephew.

Kelly, in a recent interview, calls the incident “a tragedy all the way around,” and says despite criticism that Smith seemed cold and remorseless, he was deeply troubled by what happened.

“I spent a lot of time with him in and out of court, and he was always respectful,” Kelly recalls. “I wouldn’t say he lacked remorse. He was a quiet person, and he was reserved.”

As a certified police instructor and former prosecutor, Kelly understands the stresses and challenges that come with police work. “A shooting is the most traumatic event in a police officer’s life,” he says.

Kelly has read Death by Cop and believes it’s a mostly fair and balanced account of the case. But he takes issue with Gill’s criticism of the appellate court’s decision to grant a new trial, calling it “disappointing.”

While Rev. Lewis supports Wayne Reid’s message of unity and believes that in one sense, justice was served, the underlying issues remain: Racism must still be addressed. “Yes, it still exists, but people are confronting it because they are finally beginning to see that something hideous is going on in this country in how we treat people of color,” he says.

Each time there’s news of police shooting a Black person, Reid and Gill brace for what’s to come, hoping there’s no rush to judgment, knowing that the facts behind such incidents are not always revealed at first.

“I think, ‘Oh, no. Not again. Why?’” Gill says.

“My initial thought when I see all these incidents, is that I always feel the emotional pain for the families. On both sides,” Reid says. “If applicable, prosecutors should charge an officer after meticulous investigation and not based on emotions.”

Reid believes that while the officer who killed his brother was held accountable for his actions, there really was no happy ending. “This was a unique case where there were no winners.”

He does hope to bring the story to a wider audience. Reid and Gill have been working with a producer and screenwriter to develop a feature-length movie about the case.

Write a letter to the editor, share a story tip or update, or report an error.