Tales of double-crossing, big egos and cattle brands swirl around Gerry Spence lawsuits

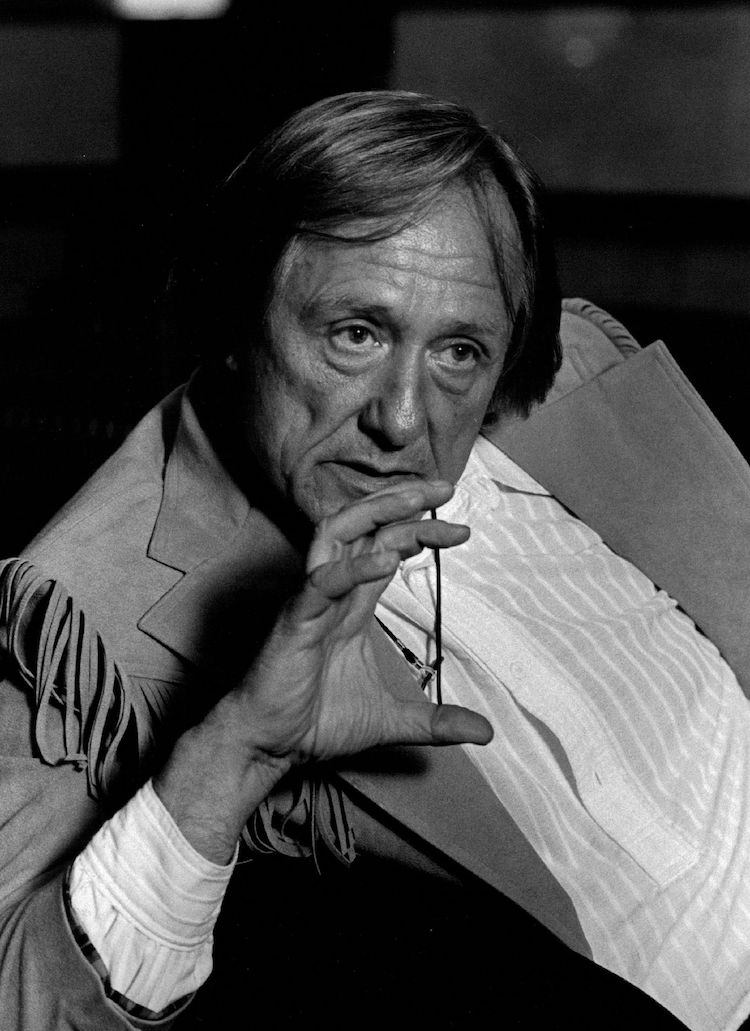

Gerry Spence. Photo By Bill Wunsch/The Denver Post via Getty Images.

Over the years, many attorneys shelled out thousands of dollars to spend three weeks in a converted Wyoming cattle ranch described as “spartan,” with no cellphone service, so they could listen and learn from the self-proclaimed “greatest trial lawyer in history.”

From all over the country, lawyers came to the Trial Lawyers College to learn from Gerry Spence, the famed litigator who claims to have never lost a criminal case. Tales of him taking on and beating big corporations were told in publications ranging from the Washington Post to People magazine.

Additionally, he’s written many books, including the 1996 bestseller How to Argue and Win Every Time, and frequently appeared on cable news television sporting a Western-cut tan leather sports jacket with fringe.

The ranch experience stopped in 2020. Since then, the TLC has been the subject of a real-life court battle pitting Spence, 92, against board members in both state and federal court. The lawsuits stem from a 2020 split of an organization once called the Gerry Spence Trial Lawyers College at Thunderhead Ranch. Spence claims some board members aren’t following his vision, while those board members say he’s suing because they denied his demand to build a multimillion-dollar conference center named in his honor.

He founded the nonprofit in 1993, which until recently was housed at a Dubois, Wyoming, acreage Spence owned. From 1975 to 1993, he bred cattle at the property while also representing noted criminal defendants including militia movement figure Randy Weaver.

The Spence Foundation, which Spence created with his wife, LaNelle, now owns the property, and it terminated the TLC’s lease in April 2020. That same month, Spence and four board members who sided with him filed a Wyoming state court complaint against the TLC seeking a dissolution of the organization, a court order to audit its books and records and the appointment of a receiver. There’s an even number of board members on each side, and they can’t agree on important business issues, according to the complaint.

The lawsuit states that TLC’s mission is to “train and educate lawyers to obtain justice for individuals, the poor, the injured, the forgotten, the voiceless, the defenseless and the damned.” According to Spence, some board members were going against that vision by representing municipalities who sue individuals for property damages. Additionally, the complaint accuses some board members of appointing or removing other board members to benefit their own agendas, not for the good of the college.

Meanwhile, from a pedagogic perspective, Spence says he started to see a pattern of overly structured teaching methods. In an affidavit, he describes himself as the organization’s founder and board chairman.

Additionally, the complaint states that some board members made threats that objections to their positions could dry up referrals. That’s not helping the college create “warriors and advocates,” the complaint states.

In a separate action filed in Los Angeles County Superior Court, Spence argued that the board members obtained a trademark on his livestock brand without his knowledge.

However, the defendants have a different story. Patrick Murphy, a Casper, Wyoming-based shareholder with Williams Porter Day & Neville, who represents the board members fighting with Spence, says his clients have followed group bylaws. According to him, they’ve identified an auditor he is working with to develop the scope of the proposed audit.

Gerry Spence.

Gerry Spence.

In the meantime, they are in the process of finding a new home and are currently offers virtual classes, with plans for in-person offerings later this year, Murphy adds. A 2017 990 tax form lists almost $8 million in assets.

Murphy says the dispute started after his clients refused to immediately build a conference center named in Spence’s honor. He claims that Spence wanted the conference center to be built in his lifetime, but the organization has raised only $281,000 for its construction, and the project would cost between $3 million and $7 million.

Additionally, Murphy states that Spence and his “loyalists” have advocated for laying off TLC’s administrative staff during the pandemic. Instead, the defense obtained a federal Payroll Protection Program loan, and the staff’s work has been vital to the organization, according to Murphy.

Almost one month after Spence filed the Wyoming state court action, the TLC brought a Wyoming U.S. District Court action alleging trademark infringement against Spence and board members who sided with him. It includes marks the organization registered in 2012 for “Trial Lawyers College” and “a stylized design of a cloud with a bolt of lightning.”

According to the complaint, the TLC accused the defense of trying to mislead the public by sending out communications with the cloud and thunderbolt logo even though they had already split.

It also alleges someone from Spence’s camp created a new listserv from the TLC database and told members the old listserv was “experiencing difficulties.” A May 27 temporary restraining order prohibits Spence from using items trademarked by the plaintiffs, making false and misleading statements related to the cloud and lightning bolt logo or the Trial Lawyers College name, and tampering with business or personal records related to the group. An appeal of the federal TRO is pending.

Spence didn’t know that James Clary, the organization’s treasurer, registered the mark until the organization sued him in May, says Rex Parris, a board member who is plaintiff in the Wyoming state court case and a defendant in the federal case.

Additionally, he represents Spence in a Los Angeles Superior Court action against Clary and other board members alleging fraud, conversion, breach of fiduciary duty and elder financial abuse, among other things. That case was filed in November.

Besides the livestock brand issue, the California action claims the organization refused to return Spence’s personal and intellectual property.

When contacted by the ABA Journal, the defendants directed all questions to Murphy. He says his clients returned Spence’s items but have been unable to get some of the organization’s belongings from the ranch. Murphy is not involved in the California lawsuit and would not comment on the livestock brand allegation.

It may not violate any laws to trademark someone’s livestock brand without their knowledge, but doing so wouldn’t sit right with many, says James Bradbury, a Texas attorney who represents ranching associations and producers.

He doesn’t know of other lawsuits about trademarking a livestock brand, but says some large ranches that also sell items like clothing and saddles have trademarked logos based on their brand design.

“There’s an interesting question, and that is: Before they got crossways and were all in the saddle together, did Spence say, ‘Yes, go ahead and use my brand?’” asks Bradbury. And if that did happen, he adds, it will likely come out in discovery.

“Realistically, what this is all about is who controls Gerry Spence’s legacy. Every person who applied to the Trial Lawyers College wanted to learn what Spence has to offer. But Spence is aging; all men are mortal. What becomes of a charismatic organization revolving around the charisma of one person? When that person is gone, what happens?” asks Norman Pattis.

A TLC graduate who also taught for the organization, he represents Spence in the Los Angeles Superior Court lawsuit and Parris in the Wyoming federal action.

Indeed, when thinking about who might be the “the next Gerry Spence,” it’s hard to come up with names, says Stephen Easton, a former dean of the University of Wyoming College of Law, who now serves as president of Dickinson State University in North Dakota.

“I don’t think there is anyone right now at the level of being as widely known as he was at the height of his fame. The old gray mare of trial work ain’t what it used to be,” says Easton, whose academic work centered on trial advocacy.

Graduates of the TLC program say they are part of a tribe even long after they leave Wyoming, and the ongoing brawl hurts their hearts.

Laura Shamp, an Atlanta plaintiffs lawyer, completed the three-week program in 2018. The experience includes exercises in psychodrama, an acting method often used in psychotherapy, where patients use role-playing and dramatic self-presentation to investigate and gain insight about their lives.

Sometimes tears were shed, but Shamp says the experience helped her be a better lawyer. It also connected her with other lawyers who have similar outlooks. She often meets with other TLC graduates in the Atlanta area to get and receive advice on trial strategy.

“They are willing to spend all day on a Saturday doing that, and they want nothing in return. I would do the same thing for them,” she says.

Write a letter to the editor, share a story tip or update, or report an error.