California Split: 1 year after nation's largest bar became 2 entities, observers see positive change

Photo illustration by Sara Wadford

For nearly 90 years, the State Bar of California hosted an annual convention that brought together hundreds of lawyers for educational programming, keynote speeches and networking.

But amid legislative scrutiny and concerns about optics, the bar’s board voted to cancel the 2017 meeting that was to be held at the Disneyland Hotel in Anaheim.

The bar association later decided to stop hosting such gatherings indefinitely, determining they were emblematic of the trade association-like activities it wanted to put in its past.

However, the so-called annual meeting for attorneys and various legal organizations was revived last year by a new group: the California Lawyers Association, known as CLA.

The nonprofit launched in 2018 to house the State Bar’s specialty law sections that were split off as part of the agency’s legislatively mandated de-unification.

During a swearing-in ceremony for CLA’s leaders at the group’s two-day convention in San Diego last September, the recently departed chair of the State Bar’s board noted the historic handoff taking place.

Photo of Michael G. Colantuono courtesy of Michael G. Colantuono

“The real significance of my presence today is to mark an important turning point in the life of the California bar,” Michael G. Colantuono told the crowd.

CLA was “accepting an entire role in our legal culture as the leaders of, and the advocates for, the legal profession,” Colantuono said. “The bar will merely regulate it.”

Colantuono was describing what he saw as one of the major shifts brought about by the split of the country’s largest state bar, an action proponents said was necessary for the scandal-plagued California agency to prioritize its regulatory duties.

The separation of the State Bar of California, created in 1927, did not come without fierce internal and legislative battles, though bar leaders and outside groups said the first year of de-unification produced the positive changes they envisioned.

The mandatory bar focused more closely on admissions and discipline for its more than 250,000 active and inactive licensees. In turn, the voluntary-membership CLA got off to a strong start taking responsibility for many of the bar’s trade association-like functions and launching new initiatives.

The case for bar associations: Why they matter

Meanwhile, the events in California have attracted nationwide attention as court rulings, active litigation and legislative pressures have prompted many of the 30-plus unified state bars to contemplate what a split would look like in their states. The U.S. Supreme Court’s June 2018 Janus v. AFSCME decision has played a key role in sparking more urgent nationwide discussions about the long-term future of mandatory state bars.

The court cited the First Amendment in ruling that public sector unions cannot force employees who benefit from a union’s collective bargaining agreement but decline to join the union to pay “fair share” fees.

Lawyers have already highlighted the decision in legal filings seeking to overturn compulsory bar fees via First Amendment arguments, and the Supreme Court in December vacated a ruling by the St. Louis-based 8th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals upholding the mandatory model so it could be reconsidered in light of Janus.

GENESIS OF A SPLIT

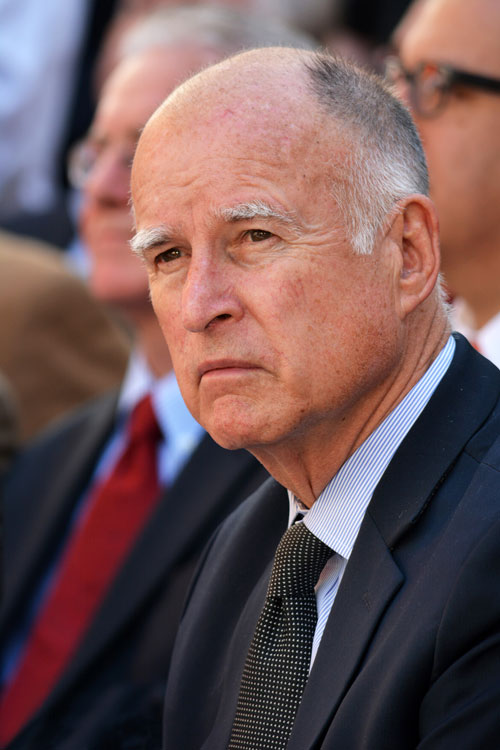

Former Gov. Jerry Brown / Shutterstock

In California, then-Gov. Jerry Brown signed the historic legislation separating the State Bar into law on Oct. 2, 2017, and it took effect at the start of 2018.

The bill, SB 36, mandated that the bar’s 16 specialty law sections depart the agency and become an independent nonprofit entity.

The sections, which focus on topics ranging from business law to environmental law, are best known for providing members with educational programming and networking opportunities. They were jettisoned to CLA along with the California Young Lawyers Association.

A primary impetus for the bar split was several years of scandals that generated frequent negative headlines and criticism asserting the State Bar was distracted from its mission of protecting the public from unethical lawyers.

The bar board’s decision in late 2014 to fire then-Executive Director Joseph L. Dunn, a former state senator from Orange County, was one major driver of widespread attention to the association’s shortcomings. While the bar typically only draws attention from the legal press, the Dunn firing and the ensuing legal battle sparked coverage in mainstream publications, including the Los Angeles Times.

Dunn, aided by media-savvy Los Angeles attorney Mark Geragos, immediately filed a suit insisting he was terminated for whistleblowing. Dunn claimed he blew the whistle on then-Chief Trial Counsel Jayne Kim’s alleged removal of cases from the bar’s backlog of attorney discipline complaints, as well as various financial and ethical improprieties.

The bar denied Dunn’s allegations while arguing that he never identified himself as a whistleblower and was fired on the basis of an outside law firm’s report. The confidential Munger, Tolles & Olson report was later leaked to the press.

The report’s authors accused Dunn of misleading, or failing to inform, the bar’s board about several important matters. For example, the report said Dunn misrepresented that California Chief Justice Tani G. Cantil-Sakauye supported a potential relocation of the bar’s San Francisco headquarters to Sacramento. Dunn was also accused of misleading the board into believing no bar funds would be used in connection with his travel to Mongolia in early 2014 to help the country set up a lawyer regulation system. (Dunn denied the allegations.)

The legal battle raged on for several years and featured a historic deposition of the chief justice. Other employees with ties to Dunn also filed suits against the bar regarding their terminations.

The bar retained Hueston Hennigan of Los Angeles, led by former Enron prosecutor John Hueston.

Dunn’s claims were the focus of a contentious five-day arbitration hearing held in a downtown Los Angeles high-rise building in early 2017 that was open to the press. JAMS arbitrator Edward A. Infante ultimately sided with the bar on Dunn’s two remaining causes of action, determining Dunn breached his duties to keep the board fully informed and to maintain a good relationship with the California Supreme Court.

“The State Bar’s evidence demonstrates that the board had a legitimate, nonretaliatory explanation for its decision to terminate claimant’s employment,” Infante wrote in his March 2017 ruling.

However, the bar’s victory came at a cost that went beyond the hundreds of thousands of dollars it spent investigating Dunn and probing the leak of the Munger Tolles report. The legal dispute was frequently highlighted by lawmakers and other bar critics as a prime example of the agency’s dysfunction.

CRITICAL AUDITS AND ARTICLES

Reports from the California State Auditor’s Office and news stories also provided plenty of fodder for the bar’s detractors.

A June 2015 audit said that in a rush to reduce its backlog of disciplinary cases, the bar allowed some attorneys who typically would have faced steeper consequences to keep practicing law through “inadequate” settlements. The report also slammed the agency’s decision to purchase and renovate a building in downtown Los Angeles for roughly $76 million instead of using the funds to improve its discipline system.

A 2016 state audit criticized the bar’s generous executive compensation, noting that the maximum salaries for the State Bar’s 13 top executives exceeded the governor’s annual salary of about $183,000. The salary for the bar’s then-executive director, Elizabeth Rindskopf Parker, was $267,500.

The state audits also generated unflattering coverage in the mainstream press, including from the Sacramento Bee.

Meanwhile, one of the bar’s outside auditors flagged concerns that year about the specialty law sections’ alcohol spending, which drew scrutiny from lawmakers, as did the sections’ venue choices for certain events.

The bar spent at least $156,000 on alcohol between January 2015 and late September 2016, most of which was tied to section events, according to information the agency provided to the state Legislature. The bar’s board later approved a ban on alcohol spending.

Also in 2016, the Los Angeles Daily Journal reported that the bar had allowed hundreds of complaints about the unauthorized practice of law by nonattorneys to sit in drawers for months without investigation. Lawmakers were furious, and the agency’s top prosecutor, Jayne Kim, resigned when it became clear she would not secure state Senate confirmation for a second four-year term.

Under the leadership of Parker and then-Chief Operating Officer Leah T. Wilson, the bar also made a legally questionable $1.6 million transfer from its Lawyer Assistance Program to its Client Security Fund that was later reversed. In addition, the agency was ordered by lawmakers to undo a building loan arrangement in which it pledged future lawyers’ dues as collateral.

The revelations gave fuel to those calling for a major bar overhaul.

Heather L. Rosing and Joanna Mendoza publicly advocated for the de-unification of the bar in submissions to the Legislature. Photos courtesy of Heather L. Rosing and Joanna Mendoza

ADVOCATES FOR REFORM

One group that had long called for a bar split with little traction was the Center for Public Interest Law. However, the University of San Diego School of Law-based center gained powerful new allies in 2016 when bar board trustees Joanna Mendoza, Dennis Mangers and Glenda Corcoran—along with former bar vice president Heather L. Rosing—publicly advocated for the de-unification of the bar in submissions to the legislature.

They wrote that splitting off the bar’s trade association-like functions, such as the sections, would allow the agency to stop being a “distracted regulator” known for its “long history of cyclical crisis, reform, neglect and renewed crisis.”

Additionally, they said creating a separate voluntary association for attorneys would ensure better legislative advocacy for the legal profession.

“We foresee a more effective regulator of legal services to Californians, and a more potent and less costly professional association for lawyers,” the group of four wrote in an April 2016 submission to the California State Assembly’s Committee on Judiciary.

Bar executives and other trustees opposed their proposals, with some trustees expressing anger in person and via email.

“This will set access to justice back decades, and hurt the very people that we are charged with protecting. I am sickened to be associated with you,” then-bar board trustee Hernán Vera wrote in a June 2016 email thread, referencing the trustees who advocated for de-unification to the Legislature.

But the reform-minded trustees found a receptive audience among the members and staff of the Assembly Judiciary Committee. The panel— chaired by Assemblyman Mark Stone, a Monterey Bay Democrat—held oversight hearings in which lawmakers slammed the bar and its executive team headed by Parker.

“I’m convinced this year the State Bar is the Titanic, and if we don’t turn it around, we will only have ourselves to blame,” Assemblyman David Chiu, a San Francisco Democrat, said during a May 2016 hearing.

While some members of the Assembly committee were eager to move ahead with a bar split, the panel decided in 2016 that the issue should be studied further by a commission.

Even that was a bridge too far for Senate Judiciary Committee Chair Hannah-Beth Jackson and Chief Justice Cantil-Sakauye. Sen. Jackson, a Santa Barbara Democrat, and the chief were fearful of going down a path that would lead to a less-than-deliberate bar overhaul.

The fiery standoff led to the 2016 legislative session ending without a bill authorizing the bar to collect lawyer fees in 2017 being enacted. In response, the California Supreme Court ordered lawyers to pay a special regulatory assessment to fund the bar’s disciplinary functions.

With the Assembly standing firm in its desire to see major changes at the bar, the resistance to a split dissipated in the ensuing months.

In early 2017, bar executives and the board agreed the agency’s sections should be separated off. Jackson and the chief justice were supportive as well. The bill crafted to de-unify the bar sailed through the California Legislature without a “no” vote.

“SB 36 supports the State Bar in our ongoing reforms to focus on our mission of public protection,” State Bar Executive Director Leah T. Wilson, who replaced Parker in September 2017, said the day the bill was signed into law.

Photo of Bridget Gramme from the University of San Diego

MANDATORY BAR REFOCUSES

Both State Bar leaders and outside groups say the agency has paid greater attention to lawyer admissions and discipline since the split.

For example, the bar spent last summer and fall preparing to implement new and amended Rules of Professional Conduct that became effective Nov. 1, 2018. A bar commission crafted the state Supreme Court-approved rules that led to the first rules overhaul in nearly 30 years.

The agency has also more actively publicized its disciplinary actions against attorneys and efforts to halt the unauthorized practice of law by nonlawyers.

The bar’s work in year one of de-unification drew praise from the Center for Public Interest Law, a group willing to criticize the agency when it falls short.

“We are heartened by what can best be described as a cultural shift at the bar—a difference in the language they use, and what appears to be a much more narrowed and clarified focus on public protection and access to justice,” said Bridget Gramme, the Center for Public Interest Law’s administrative director.

Gramme said she was encouraged the agency has looked to licensing boards from other professions for guidance on best practices and formed a Task Force on Access Through Innovation of Legal Services. “I am hopeful that this work may provide a useful model for other bars across the nation to follow,” she said.

Bar board trustee Mendoza, a member of the task force, said the panel is one way the bar is still supporting access to justice despite critics’ claims such efforts would suffer if de-unification occurred.

Reforming the agency’s various subentities to ensure greater accountability and efficiency was another key bar initiative last year. The work included examining whether more subentities should be split off, or eliminated, with plans to sunset the Committee on Mandatory Fee Arbitration moving ahead.

“We are much more sensitive to the fact we can’t let all these various committees perform the bar’s functions without proper oversight,” Mendoza said. “Rather, we have to have our finger on these things if we are going to run a government agency.”

A positive note out of Sacramento was that the bar’s funding bill for 2019 sailed through the Legislature without any lawmaker opposition.

The bill included language changes requested by the bar to reflect that it is a regulatory agency, not a bar association. Licensed attorneys are now officially referred to in the State Bar Act as “licensees” instead of “members,” and they pay “fees” rather than “dues.”

But 2018 was not without its challenges for the bar, including the financial hit it took from the loss of the sections. The bar is seeking to have the Legislature raise the $315 basic annual fee lawyers are assessed to help it address budget deficits, which the agency says have been exacerbated because there has been no fee increase in 20 years.

Also in 2018, the bar failed to secure state Senate confirmation for its chief trial counsel to serve in the role for the long term. Steven Moawad withdrew from Senate consideration amid his role as a defendant in a federal lawsuit alleging he harassed a Muslim colleague at his previous job. (He denied the allegations.)

CLA GENERATING ENTHUSIASM

Meanwhile, CLA’s leaders said the voluntary bar had a successful launch last year.

By virtue of housing the 16 specialty law sections and the California Young Lawyers Association, the group kicked off in 2018 with roughly 100,000 members, making it one of the largest bar associations in the country. For comparison, the New York State Bar Association has roughly 70,000 members.

Rosing, CLA’s first president, says the opportunity to create a new bar association from the ground up immediately generated excitement in California’s legal community.

“We are finding that our members are enthusiastic and our volunteers are enthusiastic,” Rosing says. “Equally as important, stakeholders across the state are reaching out to us on a daily basis to ask us to partner with them.”

Rosing said those stakeholders include a wide variety of bar associations, the California Supreme Court and the Legislature.

CLA has already established an Office of Bar Relations and Collaboration to partner with other bar associations on programming, education, networking and advocacy. It hired Ellen Miller-Sharp, the former San Diego County Bar Association CEO, to develop those partnerships.

California Chief Justice Tani G. Cantil-Sakauye swears in CLA President Heather L. Rosing at CLA’s annual meeting in San Diego in September 2018. Photo by Lyle Moran

In addition, CLA Initiatives focused on bolstering access to justice, diversity in the profession and civics education in schools are underway. At the group’s annual meeting, Chief Justice Cantil-Sakauye called the voluntary bar “a powerhouse with tremendous potential ahead of it.”

Rosing said another benefit of being free from the constraints applied to the State Bar as a government agency is that CLA can advocate for legislation in Sacramento that goes beyond merely regulating the legal profession or improving the quality of legal services.

In the last legislative session, CLA supported a bill—that was signed into law—to draw international arbitrations to California. It opposed unsuccessful legislation to tax high-end business services, including legal services.

The various specialty law sections are also continuing to provide technical and substantive assistance to the Legislature regarding their areas of expertise.

While CLA initially leased space from the bar in San Francisco, it moved its operations to Sacramento early this year. “We are purposely positioning ourselves very near the Capitol so we can have easy and constant access to the Legislature,” said Rosing, a shareholder at Klinedinst in San Diego.

CLA, which also leased staff from the bar, has ramped up its hiring as well. Ona Alston Dosunmu became CLA’s executive director at the start of 2019, replacing Interim Executive Director Pam Wilson. Dosunmu most recently served as vice president, general counsel and secretary at the Brookings Institution in Washington, D.C., capping a 16-year run as a member of the organization’s senior executive team.

“The skills she brings with her from the Brookings Institution are going to be invaluable to us as we grow our own membership and expand our member benefits,” Jim Hill, inaugural chair of CLA’s Board of Representatives, said when Dosunmu’s hiring was announced.

ALL EYES ON CALIFORNIA

Leaders of mandatory state bars across the nation said they have been closely watching the events in California amid precarious times for their organizations.

In Arizona, members of the Legislature have unsuccessfully tried in recent years to either abolish or bifurcate the State Bar. Some supporters of an overhaul have argued the mandatory bar model violates the First Amendment right of free association, while others have raised concerns about lawyers regulating themselves.

John Phelps, the State Bar of Arizona’s recently departed CEO, says the organization has fended off lawmakers’ restructuring attempts by highlighting the bar’s successes. But he shared that the legislative maneuverings in his state, litigation in other locales and the changes in California have forced bars to review their structures.

“Those conversations are happening across the country,” Phelps says. “In our case, we are doing some contingency planning and asking ourselves what we would need to do if we had to change our current model.”

The National Association of Bar Executives has hosted discussions at its meetings about the changing landscape facing mandatory bars, said Janet Welch, the State Bar of Michigan’s executive director. She said the topic was scheduled for further discussion at the recent NABE Midyear Meeting in Las Vegas.

Photo of Paula Littlewood courtesy of Paula Littlewood

Paula Littlewood, the Washington State Bar Association’s executive director, said the bar split in California “has set a very strong example” for bar leaders to examine.

Her state even used a document from California listing different bar functions on a spectrum to support a review of its activities.

“Each bar is unique from the next, so what worked in California may or may not work in other states,” Littlewood said. “But we certainly tried to educate ourselves a bit about what they did and how they did it.”

In September, the Washington Supreme Court announced plans to undertake a comprehensive review of the State Bar in light of both pending lawsuits and recent case law regarding the legal status of bar associations.

The court created a work group that it tasked with recommending a future structure for the bar, such as whether it should be divided into two organizations. The panel was scheduled to start meeting in January of this year, and it is expected to provide recommendations later in 2019.

LEGAL THREATS

One pending case that has drawn the close attention of state bars in the aftermath of the Janus decision is North Dakota lawyer Arnold Fleck’s federal challenge to the mandatory bar model on First Amendment grounds.

Fleck, represented by the Phoenix-based Goldwater Institute, claimed in his lawsuit he was being forced to subsidize political activities he did not support. He also highlighted that nearly 20 states regulate attorneys with voluntary bars, which he argued was evidence “attorney regulation can be readily achieved without the First Amendment burdens imposed by mandatory bar associations.”

Fleck lost at both the U.S. District Court and the 8th Circuit. But he filed a cert petition in December 2017 that sought to have the U.S. Supreme Court overrule its prior support of the mandatory bar model, such as in Keller v. State Bar of California (1990).

The U.S. Supreme Court’s December 2018 order vacating the 8th Circuit’s ruling against Fleck and remanding the case for further consideration in light of Janus was hailed by Fleck’s lawyers.

“This is a major victory, not just for Arnold Fleck, but for attorneys like him across the nation who have been forced to fund speech they don’t agree with,” Timothy Sandefur, a Goldwater Institute lawyer, said in a news release after the ruling.

However, state bar leaders believe strong legal arguments can be made that their organizations are distinguishable from labor unions, so Janus protections should not be extended to lawyers.

Photo of Janet Welch courtesy of Janet Welch

“Our members are officers of the court, they are not employees of the state,” the Michigan bar’s Welch says.

Welch says she believes state bars can also compellingly argue that the many ways in which they are integrated into the regulatory structures of government promote speech rather than suppress it. Her bar recently undertook a national survey to get a better sense of just how differently the mandatory bars around the country operate.

Helen Hierschbiel, CEO of the Oregon State Bar, also says mandatory bars stand on solid legal ground.

“We maintain that Keller v. State Bar of California is both the appropriate and the controlling case that specifically addresses the lawyer-regulatory environment, as opposed to labor unions and other nonregulatory organizations,” Hierschbiel says.

Her organization is facing a federal lawsuit two Oregon attorneys filed in August in which they point to Janus to argue they should not be compelled to pay bar dues. The Oregon bar is seeking to dismiss the suit.

THE NEBRASKA EXPERIMENT

Foreseeing the type of bar litigation playing out now, the Nebraska Supreme Court decided in late 2013 to de-unify its state bar. The court acted in response to a petition filed by Scott Lautenbaugh, a lawyer who was serving in the state Legislature. He alleged the bar association’s lobbying activities were impermissible under Keller.

While the court did not find the Nebraska State Bar Association was violating Keller, it did decide to limit the activities mandatory lawyer dues could fund to those regulating the legal profession: chiefly, admissions and discipline.

“By drawing the line for use of mandatory bar assessments well within the bounds of the compelled-speech jurisprudence, we ensure that the assessments—which will be administered by the Supreme Court—will be used only for activities that are clearly germane,” the Nebraska court wrote. “And by drawing the line in this way, we will clearly avoid the morass of continuing litigation experienced in other jurisdictions,” the Dec. 6, 2013 opinion said.

But in turning the Nebraska State Bar Association into a voluntary organization, the court created new challenges, including budgetary ones. The voluntary dues assessed were less than the mandatory ones, and lawyers were less likely to pay them, said Elizabeth Neeley, the Nebraska bar’s executive director.

The result was program and staffing cuts, and only a small number of the eliminated positions have been restored. Neeley said her association also had to make a philosophical shift.

“The beauty of a mandatory bar is that it can look outside of itself; and it can support the profession, it can support the court system and it can support the public,” she said. “One of the primary changes when you convert to a voluntary bar is you become member-centric. Your service to the court and service to the public becomes secondary, because if you don’t have members, you can’t do anything.”

Neeley highlighted that change and other issues in a letter she sent to the State Bar of Wisconsin’s CEO in April 2017 amid an effort to make bar dues in that state voluntary.

Asked if she would recommend the Nebraska approach for other states, Neeley said: “I think we have done the best we can with this model. We have really tried to make it work.”

Photo of Ellen Miller-Sharp and Heather L. Rosing by Lyle Moran

MORE CHANGE IN CALIFORNIA?

Ellen Miller-Sharp, the California Lawyers Association’s director of strategic partnerships and initiatives, acknowledges new voluntary bars have challenges they must confront.

But the longtime bar leader with experience at the national, state and local levels said she believes the opportunities for new organizations like CLA are great as well.

“To be able to start now means that you don’t have to do what other bars have done, or what the prior unified bar always did,” Miller-Sharp says. “You get to look and see what the landscape looks like and where could we add value.”

However, the California association may also become the new home for more functions the State Bar decides to spin off.

As with the annual meeting, President Rosing said CLA would welcome bar activities into its fold under the right circumstances.

“The reality is that CLA is well-positioned to take on additional responsibilities and ensure that the attorneys in the state of California continue to receive the services that they have traditionally received through the State Bar,” Rosing said.

Lyle Moran is a San Diego-based freelance reporter who specializes in legal issues. He has previously reported for the Associated Press, Los Angeles Daily Journal, San Diego Daily Transcript and the Lowell Sun.

Write a letter to the editor, share a story tip or update, or report an error.