Barrett will join Supreme Court to hear blockbuster religious freedom case

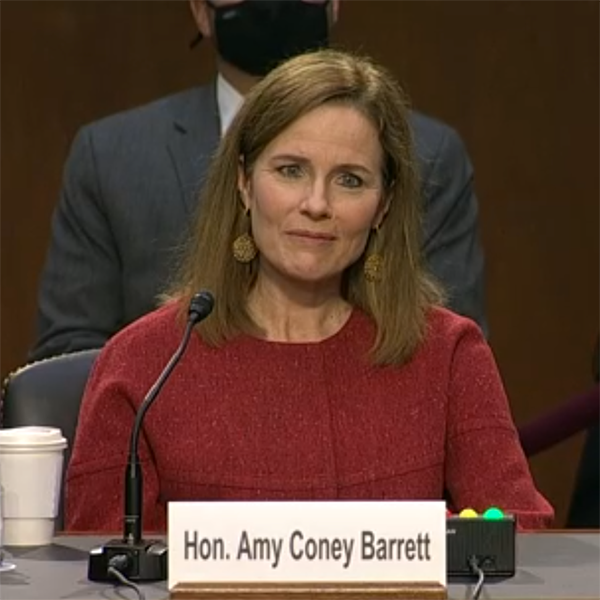

Judge Amy Coney Barrett appears at her confirmation hearings before the Senate Judiciary Committee. Image from C-SPAN.

With new Justice Amy Coney Barrett duly sworn in, the U.S. Supreme Court will soon hear arguments in one of the biggest cases of its term, which involves a clash between religious liberty claims and laws barring discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity.

The case is Fulton v. City of Philadelphia, to be argued Nov. 4, just one day after Election Day. (It is probably just the second biggest case of the November sitting. The one that got the most attention during Barrett’s confirmation hearing, California v. Texas, inovlves the future of the Affordable Care Act and will be argued Nov. 10.)

In Fulton, the justices are reviewing Philadelphia’s decision to exclude Catholic Social Services, an agency of the Archdiocese of Philadelphia, from its foster care system over the church agency’s refusal to abide by the city’s nondiscrimination policy.

Catholic Social Services argues that it has a First Amendment free exercise of religion right to decline to certify same-sex couples for foster parenthood because of the Roman Catholic Church’s teachings on marriage.

“Catholic Social Services can’t provide foster care endorsements for same-sex couples, but if [such] a couple ever asked—no one had—they would instead help them to find a foster care agency with expertise in serving LGBTQ couples,” says Lori H. Windham, a senior counsel at the Becket Fund for Religious Liberty, the law firm representing the religious agency.

Windham says there are 28 other foster care agencies in Philadelphia and three with special expertise in training and serving the LGBTQ community.

“But Philadelphia’s government says that’s not enough, and it won’t allow any more foster kids to be placed with families who work with Catholic Social Services,” Windham says.

She contends that has harmed children as well as foster parents who have worked with Catholic Social Services for years, such as Sharonell Fulton and Toni Lynn Simms-Busch, who joined Catholic Social Services in suing the city, advocates for Catholic Social Services and the foster parents say.

A ‘point of light,’ but …

Philadelphia responds in its merits brief that Catholic Social Services “has long been a point of light in the city’s foster care system” and has “performed its contractual duties with distinction.”

But “the Constitution does not grant CSS the right to dictate the terms on which it carries out the government’s work,” the city says. “CSS lacks a constitutional right to demand that it be granted a government contract to perform a government function using government funds without complying with the same contractual obligation that every other [foster family care agency] must follow.”

The city’s arguments are echoed by two organizations that intervened in the case in support of Philadelphia: Support Center for Child Advocates, which advocates for children in foster care, and Philadelphia Family Pride, a membership group that includes LGBTQ foster parents.

“While this case involves one foster care agency in Philadelphia, … it has implications for children in foster care across the country,” says Leslie Cooper, the deputy director of the American Civil Liberties Union’s LGBT & HIV Project, which represents the two intervenors. “And it could have serious consequences for children and families in a broad range of government services, such as homeless shelters and food banks, and for everyone who depends on the protections of civil rights laws.”

Catholic Social Services notes that the Catholic Church has been helping needy children in Philadelphia for more than 200 years, and the agency had an annually renewing contract with the city for 50 years, until 2018. That is when the Philadelphia Inquirer published a story about another foster care agency not conducting home studies of or providing certifications for same-sex couples.

In the article, the Philadelphia archdiocese confirmed that it had long abided by its religious-based policy of excluding same-sex couples, but also that it had not received foster care inquiries from any.

The news article sparked a back-and-forth between city officials and the archdiocese, resulting in Philadelphia’s Department of Human Services freezing foster care referrals to Catholic Social Services. The city cited its contractual language and its Fair Practices Ordinance, which bars discrimination in public accommodations based on sexual orientation and other characteristics.

“The refusal to provide services to same-sex couples constitutes a violation of a fundamental city policy to provide services to all qualified families,” the city said in a letter to Catholic Social Services’ lawyers.

Catholic Social Services, which has declined to sign city contracts since then, sued under the First Amendment’s free speech and free exercise of religion clauses.

A federal district court and the Philadelphia-based 3rd U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, in rulings refusing the church agency preliminary relief, held that city officials did not act with religious hostility toward Catholic Social Services and that the city was enforcing a neutral law of general applicability under the Supreme Court’s 1990 decision in Employment Division v. Smith, which held that government burdens on religious exercise would not be analyzed under strict scrutiny if they were neutral and generally applicable.

A city official’s comments

In granting review of the church agency’s case, the high court agreed to weigh whether Smith should be reconsidered.

Catholic Social Services argues that he city was not applying a neutral, generally applicable policy and that Smith should not have controlled the case.

“Philadelphia did not act in a neutral manner, and its policies, rather than being generally applicable, are riddled with exemptions,” Catholic Social Services argues in its brief. The city has long authorized various individualized exceptions or exemptions to its anti-discrimination policy, Catholic Social Services says.

But ultimately, advocates for Catholic Social Services call on the court to reconsider and overrule Smith.

“Smith is unsupported by the text, history, and tradition of the Free Exercise Clause—all of which guarantee broad protection for religious beliefs and practices,” Catholic Social Services says.

Douglas Laycock, a preeminent church-state scholar and law professor at the University of Virginia, argues in an amicus brief for the Christian Legal Society and other groups that Smith should be overruled. “Free exercise without exemptions … fails to avert the historic evils that religious liberty is meant to avert: coercion of conscience, suffering for one’s faith, and social conflict,” Laycock wrote.

President Donald Trump’s administration is among the dozens of groups filing amicus briefs in support of Catholic Social Services, but the administration stops short of recommending that Smith be reconsidered.

The city’s exemptions and selective applications of its policies undercut the city’s asserted interests in nondiscrimination, and thus strict scrutiny of its policy should apply, and the city cannot satisfy that high standard of review, the U.S. solicitor general’s office argues in a brief. Further, the city’s actions reflected “hostility toward Catholic Social Services’ religious views,” the brief says.

For example, the solicitor general cites comments by a Philadelphia official to Catholic Social Services that they should be listening to Pope Francis rather than archdiocesan officials regarding attitudes towards the LGBTQ community and that “times had changed,” which Catholic Social Services officials perceived to mean the church needed to change with the times as well.

“That overt hostility toward religious belief and intermeddling with religious doctrine was unconstitutional under Smith,” the solicitor general’s brief says.

If the court were to rule along the lines suggested by the Trump administration, the result could be something similar to its 2018 decision in Masterpiece Cakeshop Ltd. v. Colorado Civil Rights Commission.

That case, about a baker who refused to design a custom wedding cake for a same-sex couple, was decided on narrow grounds that the state civil rights panel had shown hostility to religion and did not resolve the larger issue of when religious liberty interests should prevail over nondiscrimination laws.

A focus on contracting

Both the city and the intervenors represented by the ACLU agree with the Trump administration on at least one point: that this case is not an appropriate one for reconsidering Smith. (And the principle of stare decisis calls for retaining Smith, the city adds.)

The ABA is among dozens of groups who have filed amicus briefs in support of the city.

Philadelphia argues that requiring a religious organization that contracts to participate in its foster care system comports with the free exercise clause.

“A government contractor who refuses to serve individuals of whom her religion disapproves, or who insists upon incorporating religious criteria into government decision-making, risks placing the government itself in the role of divvying up rights and responsibilities based on private individuals’ conformity with religious beliefs,” the city says in its brief.

The ACLU’s Cooper, representing the intervening groups, says that Catholic Social Services’ “claim is quite extraordinary and has absolutely no support in the law. CSS claims the free exercise clause gives it a right to get a government contract to provide a government service, get paid millions of taxpayer dollars to do it, and then alter the way those government services are provided to the public to comport with its own religious beliefs.”

If the court uses this case to recognize a constitutional right to a religious exemption from neutral nondiscrimination laws, the consequences will go well beyond foster care.

“It could gut nondiscrimination in government programs and beyond,” she says.

Many legal analysts believe the case presents many off-ramps for the court to avoid a major ruling or reconsideration of a significant precedent. But the case has high stakes, and with the participation of a new justice for her first major case, the interest will be intense.

See also:

ABAJournal.com: “Chemerinsky: SCOTUS considers whether religious freedom also means freedom to discriminate”

Write a letter to the editor, share a story tip or update, or report an error.