Army lawyer let Sen. McCarthy 'hang himself' through his own words, says author of new bio

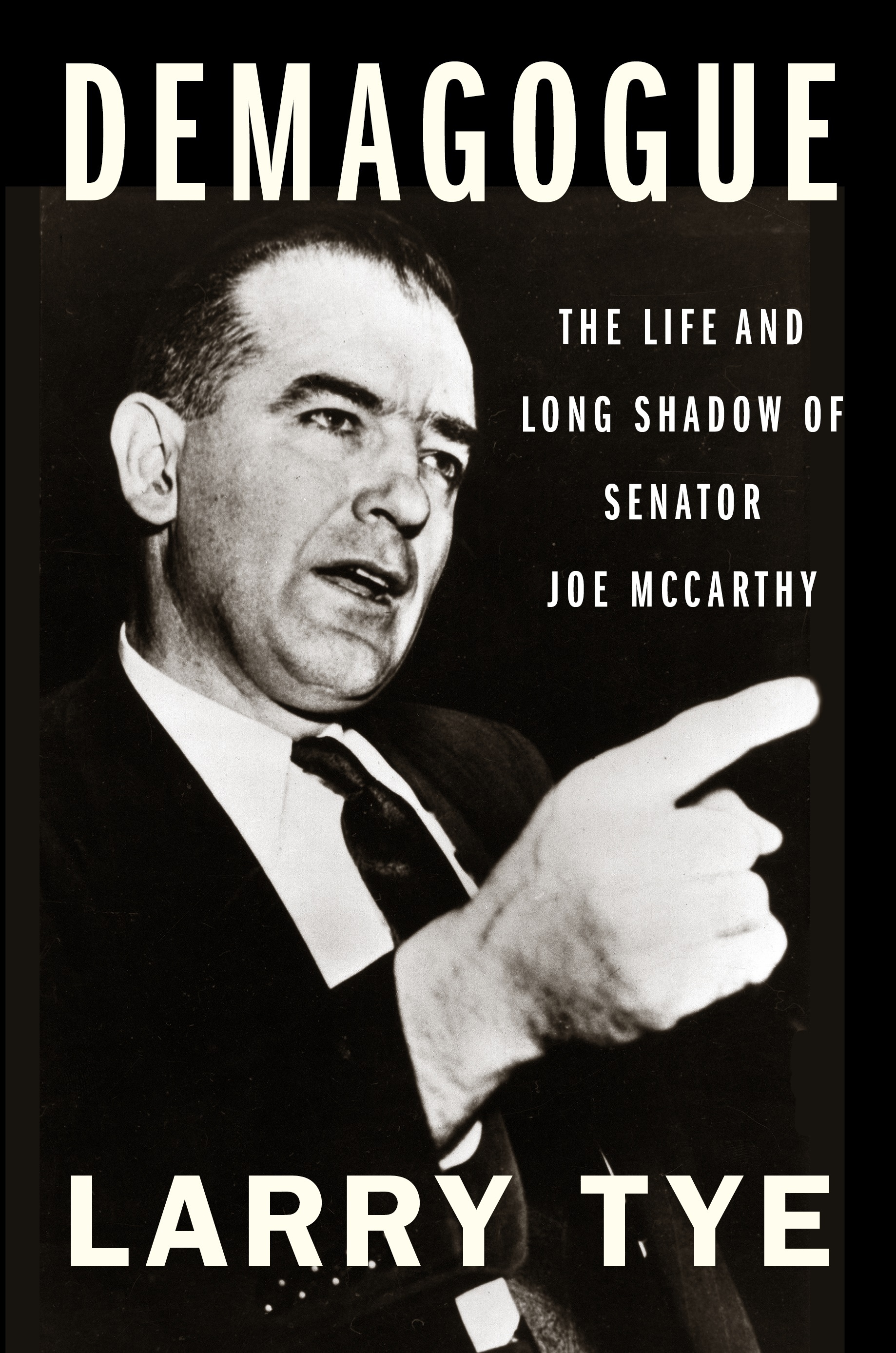

Sen. Joseph R. McCarthy in 1954. Photo from Wikimedia Commons.

They are among the most canonized words ever uttered by a lawyer, the emotional climax of the historic Army-McCarthy hearings.

Near tears, Army attorney Joe Welch reproached Joe McCarthy after the red-baiting senator slandered Welch’s young colleague: “Until this moment, senator, I think I never really gauged your cruelty or your recklessness. … Have you no sense of decency, sir? At long last, have you left no sense of decency?”

The question captured the moment perfectly, hanging in the air of the packed hearing room in Washington, D.C., and living rooms across America.

Welch’s words were no spontaneous outburst, we know now, but an assault calculated to stop the senator in his tracks. And it worked in a way that resonates today, when a McCarthy acolyte holds the nation in his grip. The leprechaun-like Welch knew that the way to slay a demagogue was to give him the rope and let him hang himself. And that’s what Sen. McCarthy, the most masterful political tactician of his era, did that afternoon of June 9, 1954.

The Army-McCarthy hearings would rightfully be compared to a soap opera, even though there was no infidelity or seduction, the plot meandered, and the only real star was a hired-gun solicitor. Joe Welch was recruited by the brother of Army Secretary Robert Stevens, who recognized that the Boy Scout of an Army boss was “unable to defend himself” against a schoolyard bully like McCarthy and his specious charges that the armed services harbored nests of Communist moles.

Welch had the air of a butter-won’t-melt-in-his-mouth Brahmin. Graduating second in his class at Harvard Law, he rose quickly to senior partner at Boston’s whitest-shoe legal firm. But he had started out poor, like Joe McCarthy, on a farm in the Midwest. Now Welch was a Bostonian, albeit with quirks. A wooden box held his supply of 150 bow ties, and the door of his office was shut most afternoons for an intra-firm game of cribbage.

He thought it terrible luck for a lawyer to enter the courtroom with a two-dollar bill in his pocket or to open his mouth, unless speech was required. “I gained stature as a public speaker by a simple device of keeping still in a room where there was often accusation, charge and countercharge and immense irrelevancy,” Welch explained. “I was seen often to sit in what was actually stunned silence but was interpreted by the audience as wise restraint.”

Whether he had ever been relaxed is questionable, but there is no doubt that any calm was shattered that climactic afternoon as the Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations neared the end of its hearings looking into McCarthy’s ferocious battle with the Army. Roy Cohn, McCarthy’s brilliant and unbridled protégé, was withering on the witness stand under Welch’s unrelenting cross-examination. Across the table, McCarthy was mad as a hornet.

Welch’s strategy

Out of the blue and beyond any bounds, McCarthy charged that Welch’s law associate in Boston, Frederick Fisher Jr., belonged to the National Lawyers Guild “long after it had been exposed as the legal arm of the Communist party.”

Seemingly distraught, Welch objected: “Let us not assassinate this lad further, senator. You’ve done enough. Have you no sense of decency?”

The question became the watchword of the Army-McCarthy saga. Cohn seemed to mouth the words “No! No!” as he frantically scratched out a note to his boss saying, “This is the subject which I have committed to Welch we would not go into.” Welch sounded more like a preacher than a lawyer as he scolded the senator, “If there is a God in heaven it will do neither you nor your cause any good.”

The audience at first seemed stunned, then, defying Chairman Karl Mundt’s long-standing admonition, it burst into loud and long applause in support of Welch and Fisher. Making no attempt to gavel for silence, Mundt declared a recess. Welch followed him out of the room. McCarthy was left behind and exposed. “What did I do?” he asked his aides, his hands spread and palms turned up. “What did I do?” Of the millions who’d heard, he alone didn’t know.

During the break Welch and McCarthy both dug in. The Army lawyer seemed to be wiping his eyes in the restroom. “Here’s a young kid with one mistake—just one mistake—and [McCarthy] tries to crucify him,” he told reporters. But as McCarthy saw it, there were no bounds in his four-year-old crusade against the communism conspiracy, and Welch had opened the floodgates by browbeating Cohn. “Too many people can dish it out,” the senator said, “but can’t take it.”

We know now there was more to the Fisher affair. Welch’s performance—from his “have you no sense of decency” speech, to near crying in front of the media—likely was rehearsed.

John Adams, the Army general counsel who wasn’t a fan of special counsel Welch, called him a “master actor” and said he overheard the lawyer asking a friend during the recess, “Well, how did it go?” Cohn at first agreed, calling it “an act from start to finish,” although the slippery lawyer later insisted there was no evidence that the famous remarks were prepared in advance.

Whether the trap was pre-planned or sprung spontaneously was beside the point. What mattered is that it was laid in the open—by Welch pushing beyond what he knew was McCarthy’s capacity for self-restraint—and the senator fell into it.

We also realize now that McCarthy’s tantrum wasn’t the first revelation of Fisher’s background, or even the second. Welch himself made it public before the hearings started, although the New York Times thought it unnewsworthy enough to give it two paragraphs on page 12 at the end of a related story.

Four days later, in a brief filed with the subcommittee, McCarthy wrote that “a law partner of Mr. Welch has, in recent years, belonged to an organization found by the House Un-American Activities Committee to be the ‘legal bulwark’ of the Communist Party.” (The Lawyers Guild in fact spent more time advocating for the New Deal and against racial segregation than pushing a Communist agenda, and most members, Fisher included, were liberal, not radical or red.)

The senator showed the discretion then not to name Fisher, even though press had. Welch and Cohn discussed the matter, and Cohn agreed his side wouldn’t discuss Fisher during the TV hearings, in return for Welch not bringing up Cohn’s draft dodging.

While McCarthy regularly threatened to “tell the ‘Fisher story,’” Fisher himself recalled, Assistant Secretary of Defense Fred Seaton had dirt on McCarthy that he thought would keep the senator quiet: “that on at least one occasion Sen. McCarthy wanted a person cleared for a government post who had a Communist background and that, as a favor to McCarthy, [Seaton] had cooperated.”

So why did the Machiavellian McCarthy break his word, risk Seaton’s revenge, and just eight days before the hearings ended, alienate much of America with his hard-hearted outing of Fred Fischer? The answer is simple, said the senator’s lawyer, Edward Bennett Williams: “McCarthy was a man who could never resist the temptation to touch a sign which said WET PAINT, and he had to touch this one.”

As for the career-shattering cost the senator paid for his outburst, New York Post columnist Murray Kempton captured that best. “You can only measure what that [audience] applause meant when you knew that two press photographers were clapping, and I have never believed before that a press photographer cared whether any subject lived or died,” Kempton wrote. “The Army, stumbling, tired and shadowed, has been handed its best witness; his name was Joseph R. McCarthy.”

.jpg) Larry Tye.

Larry Tye.

Larry Tye’s eighth book, Demagogue: The Life and Long Shadow of Senator Joe McCarthy, was published this summer by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. This article was drawn from that biography, for which Tye got first-ever access to Joe McCarthy’s personal and professional papers, along with his military and medical records.

Write a letter to the editor, share a story tip or update, or report an error.