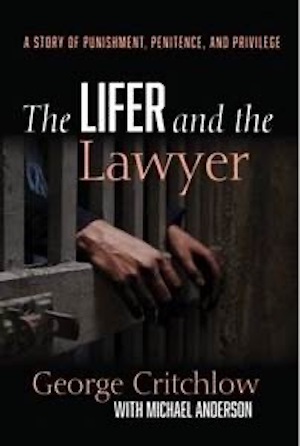

A conversation with attorney George Critchlow on his new book, 'The Lifer and the Lawyer'

“Each of us is more than the worst thing we’ve ever done.”―Bryan Stevenson, Just Mercy: A Story of Justice and Redemption

In 1979, George Critchlow was a young criminal defense attorney just a couple years out of law school. He was working at his father’s firm in the Tri-Cities, Washington, when a judge appointed him to defend the most high-profile criminal defendant in the area: Michael Anderson, an African American Chicago native who had resettled in the Tri-Cities and was charged with committing 22 offenses—including kidnapping, assault and robbery—during a violent crime spree.

In his new book, The Lifer and the Lawyer, co-authored by Anderson (Cascade Books), Critchlow recounts his defense of Anderson and how their relationship evolved from attorney-client to a lasting friendship.

Critchlow interweaves the story of Anderson’s early life of deprivation, trauma and criminal activity, with his own background as a privileged white person from a stable home with a good education and seemingly unlimited opportunity.

The book traces Anderson’s transformation from a hardened criminal and obstreperous convict to a force for good, an empathetic and giving person. His story stands as a testament to the idea that any system that aspires to justice must take into account the possibility of rehabilitation and redemption.

Anderson was sentenced to an extraordinary 10 consecutive life terms by a judge determined that “this black SOB”—in the judge’s words—would never leave prison. Despite more than 30 years of good behavior and dedication to his family and helping others, this elderly man remains incarcerated.

Critchlow is an emeritus professor, former clinical law director and former dean at the Gonzaga University School of Law in Spokane, Washington. He is also an experienced trial lawyer. He has served as a legal consultant for the ABA in Romania and Jordan and taught law in Romania as a Fulbright scholar. Further, he was instrumental in establishing Gonzaga’s Institute for Hate Studies, its MSW/JD dual-degree program, the Indian Law Program and Indian Law Clinic, and the China Comparative Law Summer Program.

Critchlow generously spoke at length on his new book. Some excerpts from that conversation follow:

George Critchlow.

George Critchlow.

On Anderson’s early upbringing

“Michael Anderson was born in 1953 and raised on Chicago’s south side in a family descended from Mississippi slaves. His biological father abandoned him at birth, and Michael had no emotional relationship with the man. Michael’s mother’s emotional history made it difficult for her to give him the support and affection he needed as an infant. She had other children and a demanding husband (Michael’s stepfather) who was not always kind to Michael.

“In time, Michael became numb, self-protective and aggressive. He dropped out of school at age 12 and looked to the streets for excitement, stimulation and status. This led to antisocial behavior, including an adolescence dominated by thievery and fighting. He started with stealing bicycles and graduated to stealing cars.

“In time, he became a burglar and armed robber. He was in and out of local jails and ultimately spent almost four years in an Illinois penitentiary for shooting a man during the course of a robbery. Fortunately, the man survived, but Michael’s prison sentence served only to reinforce and amplify his criminal contacts and proclivities. He was uneducated, self-hating, ego driven and lacking in empathy.

“After being paroled in Illinois, he and his girlfriend decided to move west (to Pasco, Washington) in the hope that a new environment could give them a new start in a calm setting and the possibility of leading productive, healthy lives.”

On Anderson’s Washington crime spree

“The most notorious aspect of his so-called crime spree involved his escape from a local Pasco jail and a subsequent home invasion, during which he tied up a family of five, stole money, assaulted and kidnapped the mother and ultimately held her and another man hostage while they drove in a stolen car to Seattle where Michael was finally arrested by a SWAT team.”

On systemic racism in the legal proceedings

“The jury was drawn from an overwhelmingly white group of people called for jury duty. I did what I could to select a jury made up of people who could judge the case on its merits and not on my client’s race. That is difficult in any case because it’s hard for people to publicly admit to prejudice even when they recognize it in themselves; harder still when people don’t recognize it and have convinced themselves they are color-blind.

“As to the judge who referred to Anderson as a “black SOB,” we discussed asking for a mistrial but decided against it for reasons of evidentiary context, trial tactics, respect for witnesses and our assumption that the judge could successfully cover his tracks.”

On permitting Anderson to testify on his own behalf

“The judge led us to believe that if Anderson took the stand and provided a foundation for enabling the jury to consider convicting him of less serious charges, then the judge would so instruct the jury. We felt Anderson’s ultimate testimony satisfied the legal standard, but the judge nonetheless ruled out the lesser crimes and basically told us we were foolish for putting our client on the stand.

“Still, the decision to have Anderson testify was his, and his motivation was only partly related to legal strategy. Yes, he wanted to take the stand to clarify a few factual details, but his primary motivation was to apologize to the family he had terrorized. The verdict in that trial was guilty on multiple charges of kidnapping and assault and one count of robbery. Together with guilty pleas entered in other proceedings, Anderson was sentenced to 10 consecutive life terms in prison.”

On Anderson’s transformation in prison

“Anderson had a spiritual transformation in his twelfth year in prison. He had been placed in a bare segregated cell at the Washington Penitentiary following a prison riot when he was approached by a Christian minister who encouraged him to ‘just believe.’ From that day forward, Anderson’s life incrementally and progressively changed for the better. The change was fundamental, convincing and enduring.

“The authentic nature of his transformation is evidenced in many ways. Not least is the fact that in the 12 years prior to his conversion, he had 68 major infractions of prison rules, including assaults, drug use, attempted escapes, rioting, insubordination, etc. Since his conversion in 1990, he has had none. His behavior reports, work history, educational programming and counseling outcomes have been stellar. He grew into a man who correctional officials trusted and who could be relied upon to mediate and reduce prison tension and violence. He worked for years in prison health clinics tending to the sick and dying.

“Perhaps most impressive is the fact that he was married in 1979 and has stayed married for 42 years. He enjoys regular conjugal visits with his wife and stays in contact with three children, five grandchildren and 15 great-grandchildren.”

“My belief is that there are many paths to redemption. Anderson’s happened to be a path revealed by evangelical inspiration and dedication. What is necessary and common to each path is changing one’s thoughts, neutralizing the source or cause of destructive impulses, and defining oneself in a new and positive way.”

On white privilege

“My hope is that the reader might glean what I think is fairly obvious. Some of us are born into situations that give us automatic and unearned advantages over those born into conditions created by historical exclusion from opportunities I took for granted in my life: opportunities for education, employment, accumulation of property and wealth, social mobility, access to power, unimpeded travel and effortless interaction with people who look the same, etc.

“In the criminal justice system, we must conscientiously examine the subtle and nuanced processes and decisions that result in a vastly disparate proportion of poor people and people of color in our jails and prisons.”

Life sentences and race

“One of every seven people in prison in the United States—a total of more than 200,000 people—is currently serving a life prison term, more than the entire prison population in 1970, before the advent of mass incarceration. Forty-eight percent of people serving life or “virtual life” prison sentences are African American and another 16 percent are Latino. The United States imprisons or jails more people per capita than any other country in the world.

“The recidivism rate for older inmates approaches zero as they reach age 70. On those rare occasions when an older inmate does reoffend, it is almost always a nonviolent crime involving a white-collar type of offense. For this reason and others, many European countries prohibit prison sentences of more than 20 years absent specific proof of psychopathy or other evidence-based risk factors.”

On their lasting friendship

“Anderson is not a client or prisoner as much as he is an admirably evolved human being. Also, I am not only his friend, but I am also no longer his lawyer. Michael was a critical collaborator in writing the book. It was Michael who encouraged me to add more of my life story because he wanted readers to know something about what made me tick in addition to my role as an observer and reporter of his story.”

Robin Lindley is a Seattle-based writer and lawyer. He is the features editor for the History News Network. Lindley’s work also has been featured in the Writer’s Chronicle, Crosscut, Documentary, NW Lawyer, Real Change, the Huffington Post, BillMoyers.com, Salon.com and more. He has a special interest in the history of human rights and conflict. He can be reached by email at [email protected].