University of Chicago Law School celebrates Earl Dickerson’s legacy as a civil rights lawyer and activist

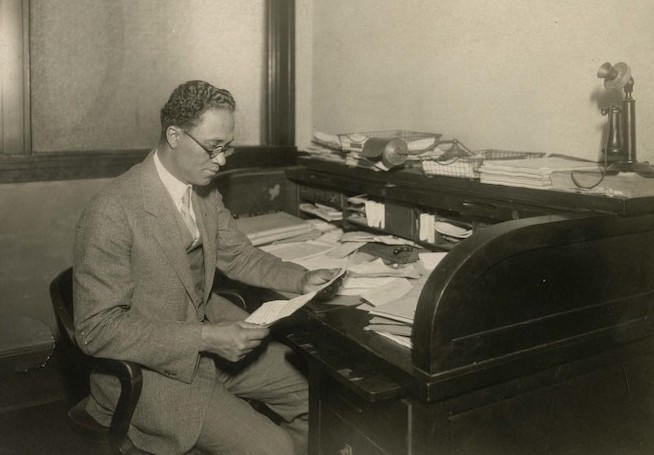

Earl B. Dickerson, who died in 1986 at age 95, filled numerous roles during his life. He was an outspoken Chicago alderman as well as the first African American appointed an Illinois assistant attorney general. Photo courtesy of Steve Brown.

Earl B. Dickerson’s name may not be well known to the public, but the civil rights lawyer lived a larger-than-life existence. Now, scholars, relatives and activists are marking the 100th anniversary of his 1920 graduation from the University of Chicago Law School in celebration of his becoming the first African American to receive a juris doctor. The school’s Black Law Students Association is named in his honor.

Dickerson also won an important case before the U.S. Supreme Court in 1940, Hansberry v. Lee, which ended a restrictive covenant that blocked African Americans from buying homes in a section of Chicago’s Woodlawn neighborhood. It’s a textbook case most students study in law school. The story behind that litigation was later fictionalized in A Raisin in the Sun, an iconic drama by the plaintiff’s youngest daughter, the playwright Lorraine Hansberry.

But that accomplishment is just one part of Dickerson’s dramatic life story. “It wasn’t until I started looking further into him that I realized, Oh my gosh—there’s so much more to him, and nobody’s talking about this,” says William Hubbard, a professor at the U of C Law School. “He was remarkable not just because he was a great lawyer, but because he did so many things, each of which embodied what it means to be a great lawyer.”

A man of many talents

Dickerson, who died in 1986 at age 95, filled numerous roles during his life. He was an outspoken Chicago alderman as well as the first African American appointed an Illinois assistant attorney general. He was general counsel of the Black-owned Supreme Life Insurance before becoming the company’s president.

He broke the color barrier as a leader in bar associations, and was also active in the NAACP and the Urban League. During World War II, he served on President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Fair Employment Practices Committee, fighting for Blacks to get a fair chance at wartime jobs and denouncing Southern segregation.

“That’s really kind of breathtaking, the scope of his contributions as a lawyer and as a citizen,” Hubbard says.

Hubbard and other law school faculty members had originally planned to mark the centennial of Dickerson’s graduation with a two-day conference and celebration in the spring, but the event was postponed because of COVID-19. The conference will now be two separate events, the first of which will be Oct. 30 via Zoom and feature a group of distinguished lawyers and historians discussing Dickerson’s work and legacy.

Organizers hope the second event, slated for April 17, 2021, can safely take place in person. Plans include a keynote address by Chicago Mayor Lori Lightfoot and remembrances by those who knew Dickerson in addition to a variety of panel discussions and artistic performances.

Although Dickerson is largely unheralded today as a player in the African American struggle for freedom, he was highly respected during his lifetime—so much so that he earned a spot near Martin Luther King Jr. during the civil rights leader’s “I Have a Dream” speech in front of the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C., Aug. 28, 1963.

“I don’t want to give the impression that my grandfather was modest, but he did not dwell on that stuff,” says Steve Brown, one of Dickerson’s grandchildren. “He was just living in the moment.”

When Brown was growing up, he didn’t hear Dickerson telling many stories about his past accomplishments. Brown didn’t know his grandfather had shared the stage with King—until it was mentioned in journalist Robert J. Blakely’s biography Earl B. Dickerson: A Voice for Freedom and Equality, published in 2006. “When I read that in the Blakely book, I was somewhat skeptical,” Brown says.

But the U of C Law School’s website later posted a photo from the historic moment, highlighting Dickerson’s face in the crowd near MLK. “That was the first time that anyone in my family ever saw any documentation of it,” Brown says.

“I don’t want to give the impression that my grandfather was modest, but he did not dwell on that stuff,” says Steve Brown, one of Earl B. Dickerson’s grandchildren. “He was just living in the moment.” Photo courtesy of Steve Brown.

“I don’t want to give the impression that my grandfather was modest, but he did not dwell on that stuff,” says Steve Brown, one of Earl B. Dickerson’s grandchildren. “He was just living in the moment.” Photo courtesy of Steve Brown.

The biography (published 12 years after Blakely died) describes Dickerson as a man of fierce convictions who was also a pragmatist. University of Chicago law professor Sharon Fairley says Dickerson’s story shows “you can be an activist just by being a really good lawyer or even a really good businessperson.”

She says Dickerson used smart procedural arguments to improve society. “That’s a theme that I hope students will take away from this. By being a good lawyer, you can make great change.”

Hansberry v. Lee is one example of that approach. On May 26, 1937, Carl Hansberry, who was Black, moved his family to a home at 6140 S. Rhodes Ave. in Woodlawn, which was an all-white neighborhood.

In his role with the insurance company, Dickerson “convinced the board of directors of Supreme Life to loan money to Carl Hansberry so that he could buy this property across the color line, which then made it possible to challenge the racially restrictive covenants that were attempting to maintain the segregated neighborhoods,” says Richard H. McAdams, U of C Law School’s deputy dean and Bernard D. Meltzer Professor of Law.

White homeowners sued Hansberry, arguing that 500 property owners had agreed to a covenant ensuring no real estate in their neighborhood could be “sold, leased to, or permitted to be occupied by any person of the colored race.” When the case reached the U.S. Supreme Court, Dickerson “wanted to argue that it was unconstitutional, but that wasn’t his only argument,” says Hubbard, who covers Hansberry v. Lee in a civil procedure class. “The backup arguments were about procedure.”

As Hubbard explains, Dickerson’s legal team also argued that the restrictive covenant wasn’t a valid contract despite an earlier court decision saying that it was. “In order to become valid, it had to be signed by 95% of the homeowners—and it hadn’t been signed by 95% of the homeowners,” Hubbard says.

The Supreme Court agreed, striking down the restrictive covenant and opening the doors for Black families to buy property on those blocks in Woodlawn. But the ruling didn’t end racially restrictive covenants everywhere else; that sweeping change would finally come in 1948 in another Supreme Court ruling, Shelley v. Kraemer.

That time, the justices agreed with the same constitutional argument Dickerson had pushed for eight years earlier in Hansberry v. Lee. Dickerson was “laying the groundwork for a court that wasn’t quite ready to take that step,” Hubbard says.

A life of firsts

Born in Mississippi in 1891, Dickerson came to Chicago in 1907 as a stowaway on an Illinois Central train. He attended Northwestern University for a year before earning a bachelor’s degree at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. After serving in the U.S. Army in Europe during World War I, he completed his law studies at U of C, carrying his service revolver for protection as he walked through white neighborhoods to attend classes during the race riot of 1919, when 38 people were killed in Chicago.

“The whole atmosphere was charged with fear and madness,” Dickerson later recalled, speaking to Blakely in one of many interviews for the biography.

Although Dickerson was not the first African American to graduate from the University of Chicago Law School—that distinction belongs to Nelson Willis, who earned a bachelor of laws in 1918—he found that his JD from the prestigious school and stellar recommendations from its faculty made no difference when it came to getting a job at an established Chicago law firm. In Blakely’s book, Dickerson recalled one of his job interviews.

The senior partner told him: “Mr. Dickerson, we would so much like to have you with us. But we are sorry. My partners would object to having a colored lawyer in the firm.” Abandoning hope of getting hired by any of Chicago’s white lawyers, Dickerson opened his own office, while beginning his work as general counsel for Liberty Life Insurance (later renamed Supreme Life).

In 1939, Dickerson became the first African American Democrat elected to the Chicago city council, where he urged improvements in public housing. In 1943, four years before the Chicago Transit Authority was created, Dickerson successfully pushed for the city to outlaw racial discrimination in the hiring of workers for the new public transit system. The city’s leading Black newspaper, the Chicago Defender, said Dickerson “put dynamite into eloquent words” when he spoke about the issue.

He wasn’t a natural politician, and Dickerson showed a “disdain for compromise,” according to Blakely’s biography. He lasted only one term as an alderman. In his final speech on the council floor, Dickerson implored the body to engage in a “fight for complete democracy of all people.”

Dickerson’s words from that 1943 speech resemble statements by today’s progressive politicians.

“When the people of my community are refused equal job opportunities,” he said, “when they are hemmed into ghettos by restrictive covenants and left to die in disproportionate number because of inadequate health and medical facilities, an improvement in their welfare should be the concern not just of their own representatives, but of every member of the elected body of the city; for we cannot have a great city free from disease, poverty and crime if we permit one large group to grow up and live under substandard conditions.”

Dickerson was active in the National Bar Association, a group for minority lawyers that formed in 1925 as a response to the American Bar Association’s refusal to accept Black attorneys as members. (The ABA changed that policy in 1943, declaring that membership “is not dependent upon race, creed or color.”) Dickerson served as the NBA’s president from 1945 to 1947.

He was also president of the National Lawyers Guild, from 1951 to 1954.

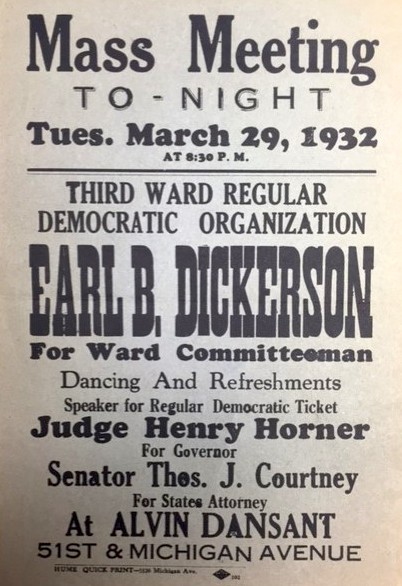

Photo courtesy of Steve Brown.

Photo courtesy of Steve Brown.

“That made him the first African American to serve as the president of an integrated national bar association,” McAdams says. “It was during McCarthyism. The National Lawyers Guild was a liberal-left legal organization, and it was under legal attack. There was an effort to have it listed as a subversive organization.” Dickerson defended the guild against this assault from the Justice Department, keeping the organization intact.

Looking back on his grandfather’s life and career, Brown says, “You sort of can’t believe that one individual was present in so many places. … The man seemed to be on top of all topics, right until the time he died at 95. … He read three newspapers a day, religiously. He still had a library. Who actually picks up a book of Milton and refers to it, or Thucydides?”

When Dickerson was 90, he gave a speech at First Chicago Center on Jan. 15, 1982, commemorating Martin Luther King’s birthday. Recalling the 1963 March on Washington, Dickerson said: “It came like a force of nature. Like a whirlwind, like a flood, it overwhelmed by its massiveness and finality.”

But nearly 14 years after King’s assassination, Dickerson was still worried about persistent racial injustice and disparity. “Through all of these years, the disproportionate rise in unemployment among Chicago Blacks, the unconscionable neglect of all-Black neighborhoods, the violence triggered when a Black boy rides a bicycle through Bridgeport—the sense of powerlessness and frustration has grown,” he said.

“From where I sit, the vision of the future is not bright on this important front. I invite each of you, here assembled today to mark the birthday of so important a man, not to wring your hands in despair or to make simple gestures of apology, but to be as active as it is humanly possible in continuing to attack and ultimately solving these problems.”

Write a letter to the editor, share a story tip or update, or report an error.