A bookish Supreme Court keeps stacking the shelves

(Image from Shutterstock)

The gift shop on the ground floor of the U.S. Supreme Court building offers all manner of knickknacks and mementos—gavels, paper weights, Christmas ornaments and neckties. But the shop is dominated by books about the court, from children’s picture books to serious biographies and legal tomes.

Increasingly, the sales shelves are packed with books written by some of the life-tenured jurists who have chambers one floor above. Four current justices have published books while on the bench, two more have deals for forthcoming books, and one retired justice has numerous titles and is still churning out books.

It seems almost quaint that in 1988, then-Chief Justice William H. Rehnquist fretted over a request from the Supreme Court Historical Society to sell a book he wrote in the gift shop it operates at the court.

“Thinking this through as best I can it seems alright to me, but I shall be very much influenced by the views of any of those of you who feel otherwise,” Rehnquist wrote in a memo to his colleagues. (Several wrote back to say they had no problem with it.)

Two fresh books, with more due soon

Among the current members of the court, Justice Clarence Thomas published a memoir in 2007, My Grandfather’s Son, in which he recounted his hardscrabble upbringing in rural Georgia and reflected on his brutal confirmation process. He received a reported $1.5 million advance from his publisher, and the book was a bestseller with some 237,000 copies sold. The normally press-shy justice even went on 60 Minutes to promote the book.

Justice Sonia Sotomayor, the first Hispanic member of the court, received a reported $1.2 million advance for her 2013 memoir, My Beloved World, which told of her youth in the Bronx and her rise through the legal profession. That book sold more than 320,000 print copies. And that memoir, along with her other books, which include a young adult edition of the memoir and several children’s books, have earned her $3.7 million.

Justice Neil M. Gorsuch’s book Over Ruled: The Human Toll of Too Much Law was released in August. (Harper Collins)

Justice Neil M. Gorsuch’s book Over Ruled: The Human Toll of Too Much Law was released in August. (Harper Collins)Justice Neil M. Gorsuch has been the lead author of two books since he joined the court in 2017, A Republic, If You Can Keep It and Over Ruled: The Human Toll of Too Much Law. Neither is a memoir but deals with judicial philosophy and challenges for the legal system. Citing industry sales data, The New York Times reported this month that those books and an earlier volume Gorsuch wrote about euthanasia collectively have sold a more modest 64,000 print copies.

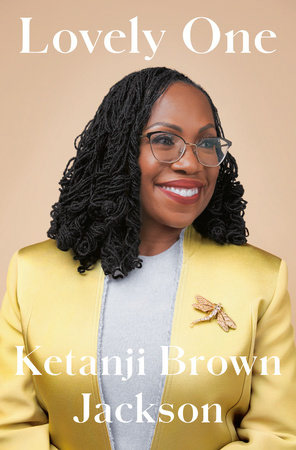

Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson is the latest to publish a memoir. Lovely One, a deeply personal account of her journey to becoming the first Black female on the court, came out earlier this month and launched her on a whirlwind publicity tour that has taken her from concert halls and Black churches to television interviews with news anchors, late-night show hosts such as Stephen Colbert and the ladies of The View.

Lovely One, a memoir by Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson, came out earlier this month. (Penguin Random House)

Lovely One, a memoir by Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson, came out earlier this month. (Penguin Random House)

“I wrote several sections from scratch myself, because I really wanted it to reflect my authentic tone and views,” Jackson told The New York Times Book Review in a recent interview during which she acknowledged a “brilliant collaborator,” who goes uncredited in the book.

Two other members of the court have books in the works. Justice Amy Coney Barrett, who joined the court in 2020, received a reported $2 million deal (she reported on her financial disclosures being paid $425,000 so far) for a book that will presumably touch on her large family and her career as a law professor before taking the bench.

Justice Brett M. Kavanaugh, who joined the court in 2018 after a contentious confirmation process, has a book contract with an undisclosed advance figure, but he reported a $340,000 payment from his publisher on his 2023 financial disclosure form.

And if books by active justices aren’t enough to satiate the public’s appetite, retired Justice Anthony M. Kennedy, who was at the ideological center of the court for three decades, has a two-part autobiography now slated for publication in 2026.

“These big advances, you’re getting them because you are a Supreme Court justice, not necessarily because your books are going to be the most blockbuster autobiography ever written,” says Stephen J. Wermiel, a law professor at American University in Washington who teaches a seminar about how the court works. (Wermiel is also a member of the ABA Journal Board of Editors)

A long tradition of justices and books

Gabe Roth, the executive director of Supreme Court watchdog group Fix the Court, notes that there have been some documented or perceived ethical breaches surrounding the justices and their books recently.

Sotomayor’s court staff helped organize book events and urged event organizers to purchase bulk copies, the Associated Press reported last year. And both Sotomayor and Gorsuch faced scrutiny over their failure to recuse themselves in court actions in which their publisher, Penguin Random House, played a role. (Sotomayor, at least, responded in a statement issued by the court that a conflict check in her chambers had failed to catch the cases involving her publisher and said she would have recused herself.)

Roth said there was nothing fundamentally wrong with the justices writing books and collecting advances and royalties.

“Justices could earn 10 times in the private sector what they are earning on the bench,” he says. “We want to incentivize public service. So I don’t begrudge them for trying to make money if they have an interesting story to tell and it doesn’t interfere with their work on the court.”

The tradition of justices writing books on the side is almost as old as the institution itself. Ronald Collins, a retired University of Washington law professor who writes about Supreme Court books for SCOTUSblog, compiled a list in 2012 of more than 350 books by the justices by that point.

The list includes a biography of George Washington by Chief Justice John Marshall in the early 1800s as well as a work Collins calls the most influential by any member of the court, Justice Joseph Story’s 1833 three-volume Commentaries on the Constitution of the United States.

“[T]he work is a rare union of patience, brilliancy and acuteness,” the American Monthly Review said in a rave the year it was published.

Story published 33 books and was “enormously influential,” Collins says.

But the most prolific was Justice William O. Douglas, who served from on the court from 1939 to 1975 and who wrote 51 books on a broad range of topics, from the environment to psychiatry to foreign policy to his two-part autobiography.

“He didn’t hold back,” Collins says. “I don’t think we’ll ever see anyone as prolific and uninhibited as Douglas.”

Aiming for a larger public audience

Wermeil, while serving as the Wall Street Journal’s Supreme Court reporter, began meeting clandestinely with Justice William J. Brennan Jr. in the early morning hours many weekdays for a biography that was eventually published in 2010 (and co-authored by Seth Stern).

No other justice seems to have followed that example, Wermeil notes. But he is fond of the book Rehnquist once asked his colleagues about the propriety of selling in the court’s gift shop. That was The Supreme Court: How It Was, How It Is, a short history of and a guide to some of the court’s inner workings.

“It’s a direct explanation from a participant on how the process works, and that is rare,” he says. “I don’t have any reasons to believe Chief Justice [John] Roberts would write a similar book.”

Rehnquist also wrote books on historical episodes that had modern relevancy, such as his works on the suspension of civil liberties during the wartime, the impeachment of President Andrew Johnson and the disputed 1876 presidential election.

Some books by the justices, including those by the late Justice Antonin Scalia and retired Justice Stephen G. Breyer, have been on topics such as legal interpretation and writing or judicial philosophy. Others, arguably starting with Justice Sandra Day O’Connor’s 2002 memoir, Lazy B, which was co-written with her brother, H. Alan Day, about growing up on their family’s Arizona ranch, have been more personal.

But unlike O’Connor and Thomas, who settled in to the high court before tackling their memoirs, recent justices such as Sotomayor, Jackson and Barrett have grabbed big advances when they were offered to them early in their tenures.

“The modern practice is to have a new justice release an autobiography soon after they are seated,” Collins says. “They’re speaking to a lay audience and a popular culture.”

To him, though, these books don’t approach the “rare union of patience, brilliance and acuteness” a reviewer once ascribed to a 19th-century justice.

“Nobody’s in Joseph Story’s league as an author,” Collins says. “We’re never seeing his like again.”

Write a letter to the editor, share a story tip or update, or report an error.