Fair Game: Does the fair use doctrine apply to Andy Warhol’s pop art?

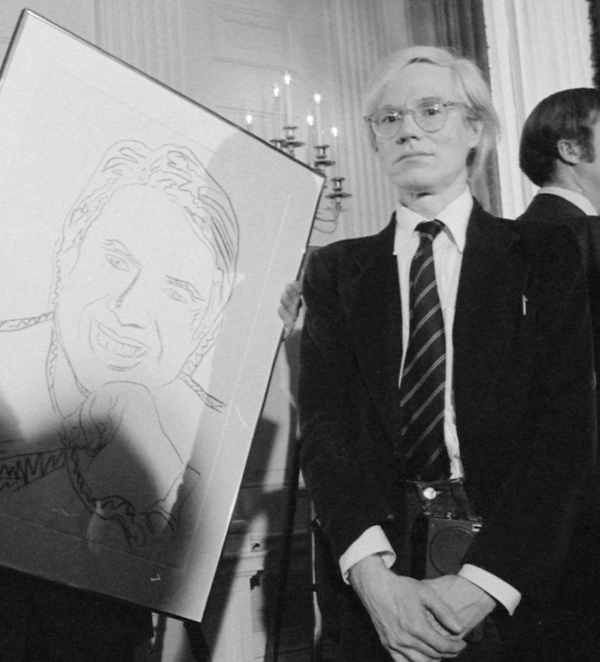

Andy Warhol in June 1977. Photo from Wikimedia Commons.

The acclaimed “Andy Warhol—From A to B and Back Again” exhibit of more than 400 of Andy Warhol’s works has been making the rounds from New York to San Francisco to Chicago. Even casual observers have a sense of Warhol’s groundbreaking pop-art style. Yet there is one surprising legal question of fair use and transformative value that begs consideration: Just what is a “Warhol”?

If Pablo Picasso or Warhol could do portraits of Lady Gaga, we can imagine the artistic transformations that might occur. If those innovations were sufficiently transformative, then such works, even when taken from other images, would likely be protected by the fair use doctrine. Yet the Picasso and Warhol examples are even much different from each other, and therein lies a nuanced distinction.

Whereas an abstract Picasso image might not bear much resemblance to its subject, Warhol’s style relies on recognition. Consider his famed portraits of Marilyn Monroe, Prince, Mao, Coke bottles and Campbell’s soup cans, among many others. His work is pop art, not abstract. Virtually all of his famous works are recognizable, yet they also have the distinctive look of a Warhol creation. Is that fair game—and, thus, does fair use apply?

What about a full-page grocery chain ad featuring NBA superstar Michael Jordan’s name while congratulating him on his NBA Hall of Fame induction? Refer to the case Jordan v. Jewel Food Stores Inc. (2014). Another example can be drawn from a noteworthy painting called “The Masters of Augusta” that featured three images of Tiger Woods to commemorate Woods’ historic first Masters win in 1997 in ETW Corp. v. Jireh Publishing Inc. (2003).

In the early 1980s, Vanity Fair magazine commissioned a Warhol work derived from a photograph of rock icon Prince. The photo was enhanced by Warhol in a manner associated with his visual artistic style. Warhol, in fact, did a series of 16 Prince images, and Vanity Fair published one of them in 1984. Years later, Vanity Fair honored Prince upon his death with an article that also used that Warhol work.

The photographer who had created the original Prince photo complained to the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, which owned the Warhol version. The foundation responded with a lawsuit to resolve whether publishing the Warhol version was fair use in The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts Inc. v. Goldsmith (2019).

The Picasso question above is hypothetical. The other matters referenced herein are real. In one, the Jordan incident, the use was found to infringe on Jordan’s right of publicity, primarily because it involved commercial speech, which has a weaker free speech protection.

With the Warhol case, the federal court ruled last July that the Warhol image of Prince was a fair use based on the argument of transformative value. That begs the key question: When does a Warhol become a “Warhol”? For infringement purposes, this answer will do: when its transformative value overcomes an otherwise unfair use. Ergo, in the case of a famous artist with a famous style, does this mean that the work is sufficiently transformed just because that famous artist enhances it?

For the Tiger Woods prints, the court considered the alleged violation of Woods’ publicity rights. This also required an analysis of fair use. Artistic expression can be a valid use of another’s image, and art is given greater latitude than mere commercial speech—even though these prints were ultimately sold for profit. The artist won, but many experts criticized the decision.

What then puts the “transformation” into “transformative value”? If a local shoemaker takes a photo of NFL quarterback Tom Brady and uses it to sell a new line of shoes, there is more commercial exploitation than art involved. But if the shoemaker paints a picture of Brady from that same photo and then sells it, is that art? Probably. And if there is sufficient transformative value, his art might even be protected.

Marilyn Monroe in the 1953 film Niagara. Photo from Wikimedia Commons.

Marilyn Monroe in the 1953 film Niagara. Photo from Wikimedia Commons.

Warhol’s groundbreaking early diptych work of Monroe, created in the early 1960s, just after her death in 1962, comprised 50 likenesses of her taken from the star’s publicity photo for the feature film Niagara.

All the portraits had a black overlay applied with a silkscreen process, giving them a unique appearance. The left half of the work displays 25 color images to symbolize Monroe’s vibrant stardom, while 25 fading black on silver images on the right side represent her death.

Had the owner of that publicity photo complained, the transformative-value argument for this fledgling Warhol may not have been as compelling as it is today. But if the original Monroe art was not really a “Warhol” as we think of that term now, it quickly became a Warhol when his pop-art style swept the art world just as the Monroe image was becoming one of the most influential works of modern art.

If an unknown artist like the hypothetical shoemaker above, a random painter or a very young Warhol repaints an image of Monroe, Lada Gaga or Prince, then sells it, the transformative value would not be influenced by the artist’s unique reputation. But what happens when a famous Warhol creates a work in his own inimitable style? It is, by definition, a Warhol, and that may be a self-fulfilling transformation, as well.

In ruling on Prince, the district court judge found that, “The Prince Series works can reasonably be perceived to have transformed Prince from a vulnerable, uncomfortable person to an iconic, larger-than-life figure.” Counsel for the photographer argued that such reasoning erodes her rights in favor of famous artists who make cosmetic changes. Therefore, a Warhol becomes a Warhol, in no small part, because Warhol does it.

Transformative value seems to be a moving target. Too simplistic? Perhaps not, especially when Warhol turns it into a Warhol as a valid artistic expression. If Warhol does it, or Picasso or even Salvador Dali, then that says a lot—especially if they do it in their own recognized style. But what if someone else does a Warhol-like impression of a famous subject?

Consider the well-known Barack Obama “Hope” poster. An Associated Press photograph of Obama was converted by artist Shepard Fairey into an engaging image and then into a poster labeled “HOPE.” The original AP copyrighted photo was taken at a 2006 National Press Club event. Fairey removed a background flag, then enhanced the photo with a new background and contrasting color and added a lapel pin for Obama’s suit. Fairey made and sold the posters.

But was his use unfair under the law? The poster surely looked like Obama, and to the untrained eye, it looked much like the copyrighted photograph redone as a Warhol-like image. The AP claimed infringement and sued Fairey in Fairey v. the Associated Press (2010). The AP and the artist later agreed to collaborate on the poster and on additional AP photos, so the case settled without resolving the key copyright issue. Still, the pattern manages to evoke the “What is a Warhol?” type of question.

Even if the Obama poster was inspirational, a “Fairey” work apparently was not as compelling for an argument of protection as an established Warhol, even though the finished poster had Warhol-like traits. Thus, if Warhol does a Warhol, it’s transformative, but if a guy named Fairey does a Warhol impression, it is not? It almost seems more transformative to create an Obama poster transformed in a Warhol-like manner. One might also wonder whether it is a parody of a Warhol.

Meanwhile, an actual Warhol done like a Warhol seems to carry a lot of transformative value, leaving this paradoxical question: If an image of Prince looks like Prince and a Warhol at the same time, does the Warhol version win? Yes, at least for fair use. But wait: What about copying Prince’s music, not his image? This raises different questions about infringement and fair use parody. In other words, “When is a Weird Al Yankovic a Weird Al”?

Eldon L. Ham.

Eldon L. Ham.

My background and advice

Much of my 43 years of legal experience has been in sports and entertainment law, including matters on endorsements, licensing, trade secrets, trademarks, copyrights, fair use and public domain issues, and infringement.

My suggestion to lawyers entering or engaging in the practice of sports, entertainment, music and related intellectual property matters is to be a lawyer first: View issues of fair use, public domain, parody, trade secrets and infringement outside the box and through the lens of legal analysis.

Above all, be able to distinguish facts and cases for and against your position. Keep asking why and raising questions about the intent and purpose of the proprietary matters behind trade secrets, parody, exploitation, trademarks and copyrights.

Be persistent, especially with the federal trademark office. The U.S. Patent and Trademark Office pushes back a lot on trademark registrations, but it is staffed largely by competent lawyers who appreciate a well-grounded argument about categories of words, use and infringement.

Remember, the fundamental premise of a question or issue. When is a Warhol a “Warhol”—and why?

The exhibition, “Andy Warhol—From A to B and Back Again,” is showing at the Art Institute of Chicago through Jan. 26.

Eldon L. Ham is a member of the faculty at the Illinois Institute of Technology’s Chicago-Kent College of Law, where he has taught since 1994. He is also the designated legal analyst for WSCR Sports Radio in Chicago and is the author of five books on topics of sports history.

ABAJournal.com is accepting queries for original, thoughtful, nonpromotional articles and commentary by unpaid contributors to run in the Your Voice section. Details and submission guidelines are posted at “Your Submissions, Your Voice.”

Your Voice submissions

The ABA Journal wants to host and facilitate conversations among lawyers about their profession. We are now accepting thoughtful, non-promotional articles and commentary by unpaid contributors.