The Supreme Court seems bitterly divided. Two justices say otherwise

Justices Sonia Sotomayor, left, and Amy Coney Barrett during a panel discussion at George Washington University on March 12. (Jahi Chikwendiu/The Washington Post)

The bitter confirmation battle was behind her, and Amy Coney Barrett was the nation’s newest Supreme Court justice—a conservative protégé of the late Antonin Scalia whose antiabortion bona fides helped make her President Donald Trump’s pick to cement a 6-3 supermajority.

She was still celebrating at the White House when she received her first congratulatory phone call from the high court. On the line: Justice Sonia Sotomayor, the court’s leading liberal, an Obama nominee and the first Latina on the bench.

The unlikely pair are now headlining joint public appearances to make the case for disagreeing more agreeably at a time when the country is more polarized than ever and public opinion of the Supreme Court is at historic lows, with approval divided sharply along partisan lines.

The justices are at the center of a huge number of politically consequential disputes, all falling in an especially polarized presidential election year. The opinions they issue from their stately courthouse, in view of the U.S. Capitol, often contain heated language and reveal vigorous disagreement. But sitting side by side onstage at two recent events, Barrett and Sotomayor insisted the vitriol ends there.

“When we disagree, our pens are sharp,” Sotomayor said, turning to look at Barrett. “But on a personal level, we never translate that into our relationships with one another.”

It doesn’t hurt, she and Barrett said, that their lifetime tenure on the bench means they are somewhat insulated from politics and not beholden to the presidents who appoint them. And the nine justices spend lots of time with one another, eating lunch together most days the court is in session and typically holding two private conferences a week to discuss the cases before them. Barrett and Sotomayor sit across the table from each other at lunch, in assigned seats that belonged to their predecessors.

“We don’t sit on opposite sides of an aisle. We all wear the same color black robe. We don’t have red robes or blue robes,” Barrett told a gathering of the National Governors Association last month as part of its Disagree Better initiative. “Our loyalty lies to the Constitution and the court.”

At times, a moderating voice

Back in 2020, Democrats cried foul when Republicans muscled Barrett’s confirmation through the Senate without bipartisan support, just one week before the election Trump lost to President Biden. It was an especially bitter fight because Mitch McConnell, then the Senate majority leader, had blocked President Barack Obama’s final nominee, Merrick Garland, eight months before Trump was elected.

Barrett, an appeals court judge and longtime Notre Dame law professor, was cast by Democrats as a threat to health care and reproductive rights. Her replacement of liberal icon Ruth Bader Ginsburg paved the way for the newly configured conservative majority to quickly eliminate the nationwide right to abortion and overturn Roe v. Wade after 50 years. Barrett also aligned with the other Trump nominees to end race-conscious college admissions policies, expand gun rights and invalidate Biden’s student loan forgiveness program.

Justices Sonia Sotomayor and Amy Coney Barrett discuss building bridges and “lowering the temperature” on the court. (The Washington Post)

But the justice has emerged as a moderating voice in other areas, more in line with Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. and Justice Brett M. Kavanaugh—both conservative but often less so than Justices Clarence Thomas and Samuel A. Alito Jr.

She has been increasingly outspoken in calling for narrow rulings and less heated rhetoric.

One of Barrett’s recent appearances with Sotomayor came just 10 days before the high court’s ruling to keep Trump on 2024 presidential election ballots, reversing a Colorado decision that disqualified the former president from returning to office because of his actions around the Jan. 6, 2021, attack on the Capitol.

By the time the two justices took the stage at the governors’ conference in Washington, they surely knew the outcome of the much-watched case. While the decision not to bar Trump from the ballot would be unanimous, the ruling included plenty of pointed disagreement—tucked into two concurring opinions, which judges typically write when they agree with the outcome but for different reasons.

Barrett agreed with Sotomayor and the two other Democratic-nominated justices that their colleagues—Roberts, Kavanaugh, Thomas, Alito and Neil M. Gorsuch—had gone too far by dictating in their opinion how to enforce a long-dormant section of the Constitution designed to prevent insurrectionists from holding office.

Barrett parted ways with the liberals, however, when they accused the majority of trying to insulate the court and Trump from “future controversy” and to “insulate all alleged insurrectionists from future challenges to their holding office.”

Writing separately, she emphasized that “particularly in this circumstance, writings on the Court should turn the national temperature down, not up.”

“For present purposes, our differences are far less important than our unanimity,” Barrett added, speaking directly to the public. “All nine Justices agree on the outcome of this case. That is the message Americans should take home.”

Harvard Law professor Noah Feldman said Barrett’s writing in the Colorado case shows she “cares a lot about the legitimacy of the Supreme Court and wanted to emphasize the court’s unanimity.” He noted that the justice had memorably said in 2021 that she hoped to convince Americans that the justices were not “a bunch of partisan hacks.”

“Where possible,” Feldman said, “the court should speak with a single voice, especially on matters of election law and matters involving the presidential election.”

But that does not mean Barrett has managed to avoid politics altogether. Her 2021 speech was introduced by McConnell, who had fast-tracked her confirmation and facilitated Trump’s transformation of the federal judiciary.

And even as she sought to take the high road in the Colorado ballot case, Barrett took a shot at her liberal colleagues, including Sotomayor, in her concurrence, writing: “In my judgment, this is not the time to amplify disagreement with stridency.”

Barrett’s chiding of the liberals and use of the word “stridency” was perhaps not the best way to turn down the temperature, Feldman said. He added that Barrett’s vote to overturn Roe—the long-standing court precedent whose reversal led to heated rhetoric and public mistrust of the court’s legitimacy—is also part of her record.

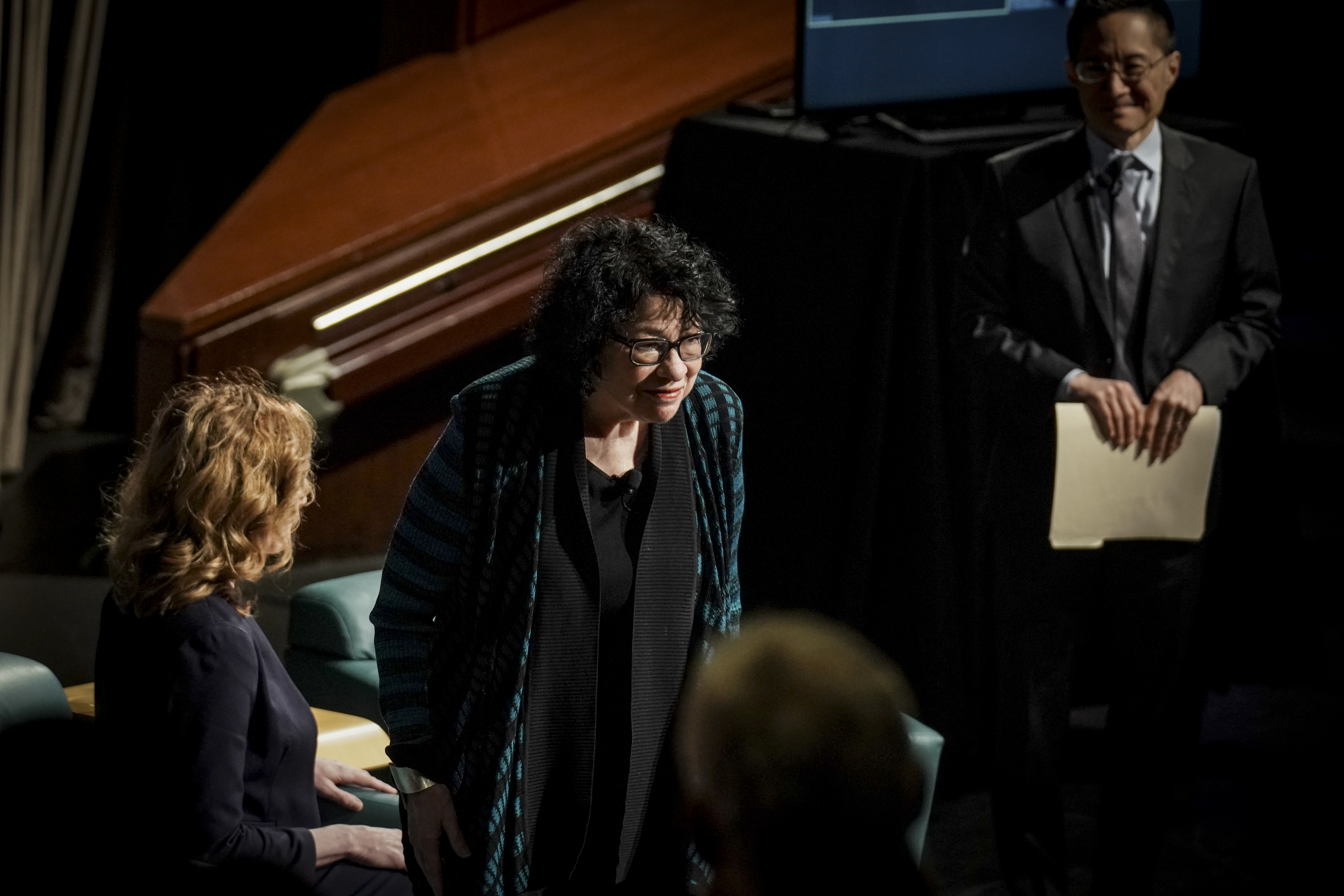

Sotomayor and Barrett at George Washington University. (Jahi Chikwendiu/The Washington Post)

Sotomayor and Barrett at George Washington University. (Jahi Chikwendiu/The Washington Post)

Barrett and Sotomayor are not the first pair of justices with differing views to make joint public appearances or forge close personal ties. Ginsburg and Scalia were the court’s most storied odd couple, attending the opera and traveling together. Scalia and retired Justice Stephen G. Breyer, a Clinton nominee, engaged in public debate over how to interpret the Constitution. Gorsuch, a Trump nominee, and Elena Kagan, an Obama pick, taught together in Iceland in 2021.

“This is not a new concept, but it’s never been more important than it is right now,” Stanford Law professor Jeffrey Fisher, co-director of the Supreme Court Litigation Clinic, said of the joint appearances.

As students on college and law school campuses—and the public more broadly—struggle with how to tolerate differing points of view, Fisher said, “we desperately need models for civil discourse across disagreement.”

The justices like to point out to their audiences that they agree more often than they divide along ideological lines. During Barrett’s first three terms, the court was on average unanimous in 41 percent of cases, according to Adam Feldman, the founder of Empirical SCOTUS. In the cases that split the court last term, Barrett and Sotomayor voted together 55 percent of the time.

In some ways, it may be easier for Barrett to call for comity than some of her liberal colleagues, given that she is more often on the winning side of big decisions. But she has also demonstrated an interest in narrow, less disruptive rulings in some cases.

She was in the majority in 2021 when the court rejected an emergency request from Maine health-care workers to block a coronavirus vaccination mandate that did not include an exception for religious objectors. She joined the court’s three liberals, as well as Roberts and Kavanaugh, and wrote separately to say the court should not make such a decision “on a short fuse without benefit of full briefing and oral argument.”

The same year, the court found a narrow way to rule unanimously that Philadelphia must continue to allow a Catholic agency to participate in vetting potential foster-care parents even though it does not accept same-sex couples. While the court’s most conservative members were put off by the limited scope of the opinion, Barrett disagreed. She said the justices need not take an additional step to overturn a 1990 precedent, seeing “no reason to decide in this case whether Smith should be overruled, much less what should replace it.”

Barrett and Sotomayor are stylistically quite different on the bench and in their writings. Barrett’s former boss and mentor, Scalia, was known for fiery rhetoric, but the former professor has said that’s not her style. During oral argument, her questions tend to be technical and professorial, reflecting a high degree of preparation.

In contrast, Sotomayor tends to use more biting language. When the court sided last term with a Christian business owner who did not want to provide services for gay couples, she wrote the dissent, calling it a “sad day in American constitutional law and in the lives of LGBT people.”

And as the court appeared poised to overturn Roe at oral argument, Sotomayor asked: “Will this institution survive the stench this creates in the public perception, that the Constitution and its reading are just political acts?”

Barrett and Sotomayor before their conversation with moderator Eric Liu, right, at George Washington University. (Jahi Chikwendiu/The Washington Post)

Barrett and Sotomayor before their conversation with moderator Eric Liu, right, at George Washington University. (Jahi Chikwendiu/The Washington Post)

‘We don’t raise voices’

Relations on the court have been tested and at times strained in recent years. After the 2022 leak of the court’s draft opinion to overturn Roe, Alito said the unprecedented betrayal of trust “certainly changed the atmosphere at the court.” The justices also struggled under pressure from Democrats in Congress to agree on an ethics code in response to media reports of lavish trips and gifts that some justices received from billionaire friends.

But Barrett and Sotomayor, who did not respond to interview requests for this story, did not focus on those tensions in their joint appearances this week and in late February. Instead, they emphasized the importance of cultivating collegiality, describing conversations about family, television shows, books and sports during their workday lunches.

Those in-person gatherings are critical, Barrett and Sotomayor said, when it comes to tackling tough issues in the conference room with only the justices in attendance.

“We don’t raise voices, no matter how hot-button the case. We always speak with respect,” Barrett said Tuesday during the National Forum of Civic Learning Week at George Washington University, sponsored in part by iCivics, the nonprofit started by the late Justice Sandra Day O’Connor.

“Even if, inside, you are frustrated or hot under the collar, you don’t express that in the conference room.”

Sotomayor mostly agreed but said when it comes to certain issues “important to people in a more visceral way,” colleagues have come close at times to saying “something that could be viewed as hurtful.” In those instances, Sotomayor said, one of the more senior justices has encouraged an apology or “patching it up a little bit.”

And it’s not that collegiality changes your principles, the justices added.

“I may disagree with how many of my colleagues approach these questions, but I’m very vocal about that disagreement, and I lay out why I think they are wrong, and I hope some day they’ll see the error of their ways,” Sotomayor said Tuesday, prompting Barrett and the audience to erupt in laughter.

Barrett joked that the relationship among the nine justices is something like an arranged marriage with no opportunity for divorce.

“We’re not going anywhere, so we have to get along,” she said. “But shouldn’t that be true of all of us in a civic community? Why should any of us want to obliterate the opposition or even see another person as the opposition? I think we should all be trying to get along.”

Akhil Amar, a Yale Law School professor, who was the first to interview Barrett and Sotomayor together, in 2022, said Barrett “is a cautious person; she’s not a bomb thrower.”

He encouraged the pair to appear together more often.

“The country,” he said, “needs to see more of that.”

Write a letter to the editor, share a story tip or update, or report an error.