Suit filed against Louisiana law requiring Ten Commandments in classrooms

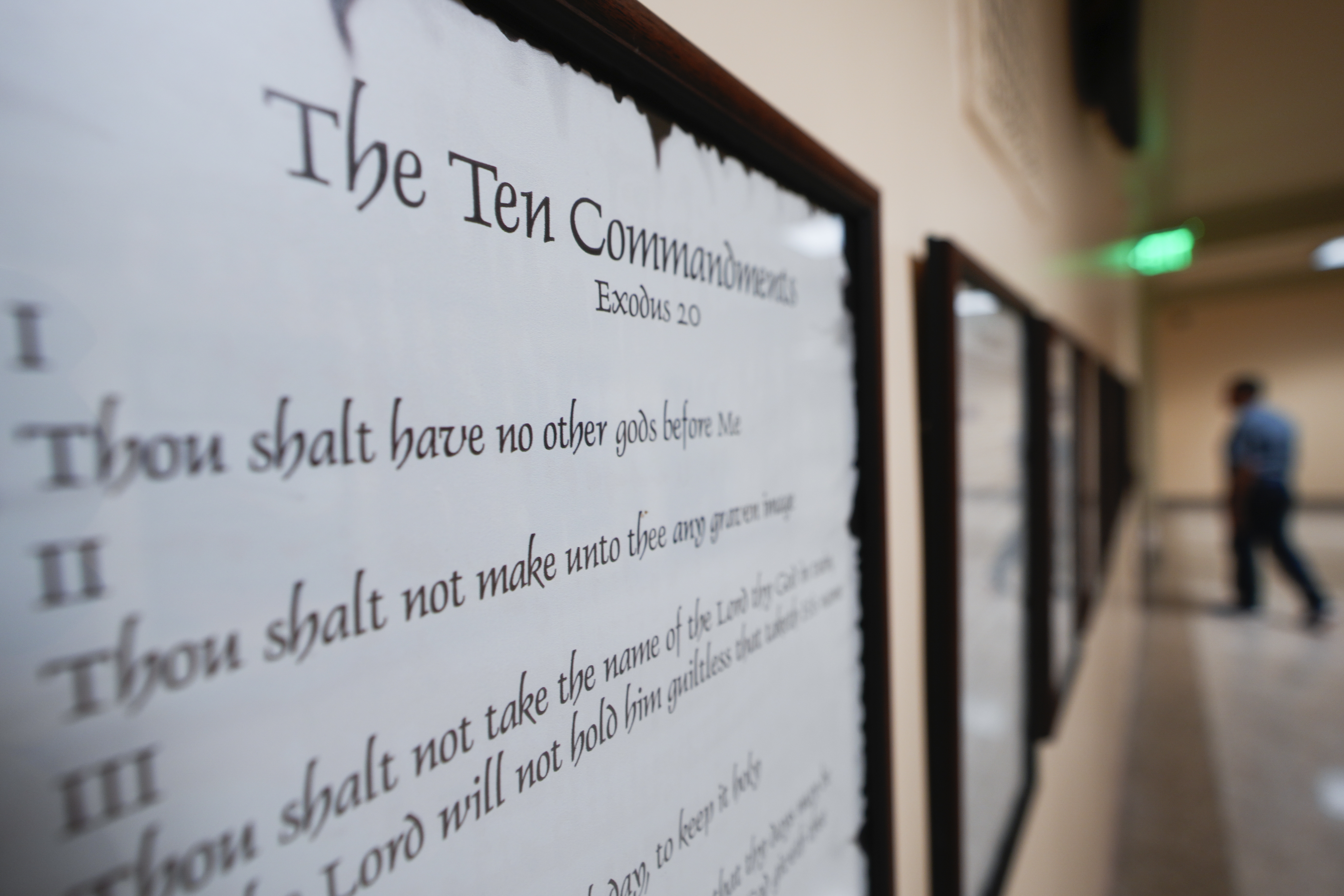

A copy of the Ten Commandments is posted along with other historical documents in a hallway of the Georgia Capitol, Thursday, June 20, 2024, in Atlanta. Civil liberties groups filed a lawsuit Monday challenging Louisiana’s new law that requires the Ten Commandments to be displayed in every public school classroom. (AP Photo/John Bazemore, File)

A coalition of groups filed a lawsuit Monday against the state of Louisiana’s new requirement to post the Ten Commandments in every school classroom, claiming parents’ rights are violated by the new law.

“Permanently posting the Ten Commandments in every Louisiana public-school classroom—rendering them unavoidable—unconstitutionally pressures students into religious observance, veneration, and adoption of the state’s favored religious scripture,” says the suit, which charges that there is no long-standing tradition of hanging the commandments in classrooms and that courts have already ruled against the practice.

The suit was filed in U.S. District Court by the Freedom From Religion Foundation, Americans United for the Separation of Church and State, and the American Civil Liberties Union’s national and state offices. The plaintiffs include nine Louisiana families of different faiths, among them four members of the clergy.

At an afternoon news conference, some of the rights groups said the case has national import.

“We are at an inflection point in Louisiana and also in the United States. This is a reckoning that has been in the making since the civil rights movement. I suggest we’re in the civil rights movement of our generation. This is a choice we’ll make and it’s about whether we move towards light, hope and freedom or if we choose to live in darkness and to promote despair,” said Alanah Odoms, executive director of the state’s ACLU. She said the law, called HB71, “is the canary in the coal mine.”

The groups, which work to protect church-state separation, had said last week they would challenge the law, which was signed Wednesday by Gov. Jeff Landry (R) and is the first of its kind in the country since 1980, when the Supreme Court ruled a similar Kentucky law unconstitutional.

State Attorney General Liz Murrill said Monday she hadn’t seen the suit yet, but pointed to a pending U.S. Supreme Court case in which Louisiana is accusing the Biden administration of censoring conservative views, and a January conviction of six abortion opponents who blockaded a Tennessee abortion clinic. In the first case, the administration said it only made requests to remove misinformation.

“It seems the ACLU only selectively cares about the First Amendment - it doesn’t care when the Biden administration censors speech or arrests pro-life protesters, but apparently it will fight to prevent posters that discuss our own legal history,” she said.

Last week, appearing on the conservative cable channel Newsmax, Murrill noted that the law calls for the scripture to be posted with “context” describing the Ten Commandments as a “prominent part of American public education for almost three centuries.” She said the effort to add “context is our legislature trying to thread the needle. … This has yet to be played out, and I certainly plan to give legal guidance to our school system.”

Heather Weaver, ACLU staff attorney for Freedom of Religion and Belief, said there is no context that could justify a permanent, prominent version of the Ten Commandments that comes from a specific Protestant text, as the legislation requires.

“It’s especially egregious because they’re posting it in every classroom, clearly trying to draw students’ attention to the displays in a way that’s extremely problematic,” she said at the Monday afternoon conference. “There is no reason for that, it wouldn’t be tied to any academic lesson.”

The new law gives schools until Jan. 1 to display the Ten Commandments on “a poster or framed document that is at least eleven inches by fourteen inches” in every classroom. The commandments have to be the display’s “central focus” and be “printed in a large, easily readable font,” the law says.

The Rev. Jeff Sims, a Presbyterian pastor, father of three Louisiana public school students and plaintiff, said the law is a “gross intrusion” of government into private faith.

“I want my children to understand scripture in the context of our faith, which honors God’s diversity and preaches all people are equal. This law interferes with my religious freedom—it tramples on it,” he said. “We have a separation of church and state in this country to prevent just this kind of government overreach. As a pastor and father I can’t sit by silent while our political representatives usurp God’s authority for themselves.”

Rights groups’ attorneys Monday said they felt confident that if the case got to the U.S. Supreme Court the law would lose.

“Looking at many years of [Supreme Court rulings] there is extreme concern about coercive practices on children,” said Patrick Elliott, legal director at the Freedom From Religion Foundation.

Since the law was passed, church-state law experts have noted that the legal metric used in the 1980 case was in 2022 set aside by the current conservative court. The so-called Lemon test was in place for more than 50 years to decide whether a law violates the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment, asking whether the government was being “excessively” entangled with religion, or whether a particular law harmed or boosted religion—rather than staying neutral.

The court in 2022 suggested it will look at history, tradition and the text of the Constitution.

“Now we are in somewhat uncharted territory,” Michael Helfand, a professor focused on religion and ethics at Pepperdine University’s law school, said last week of how the Louisiana law might fare.

Write a letter to the editor, share a story tip or update, or report an error.