Meet the Delaware judge who keeps foiling Elon Musk

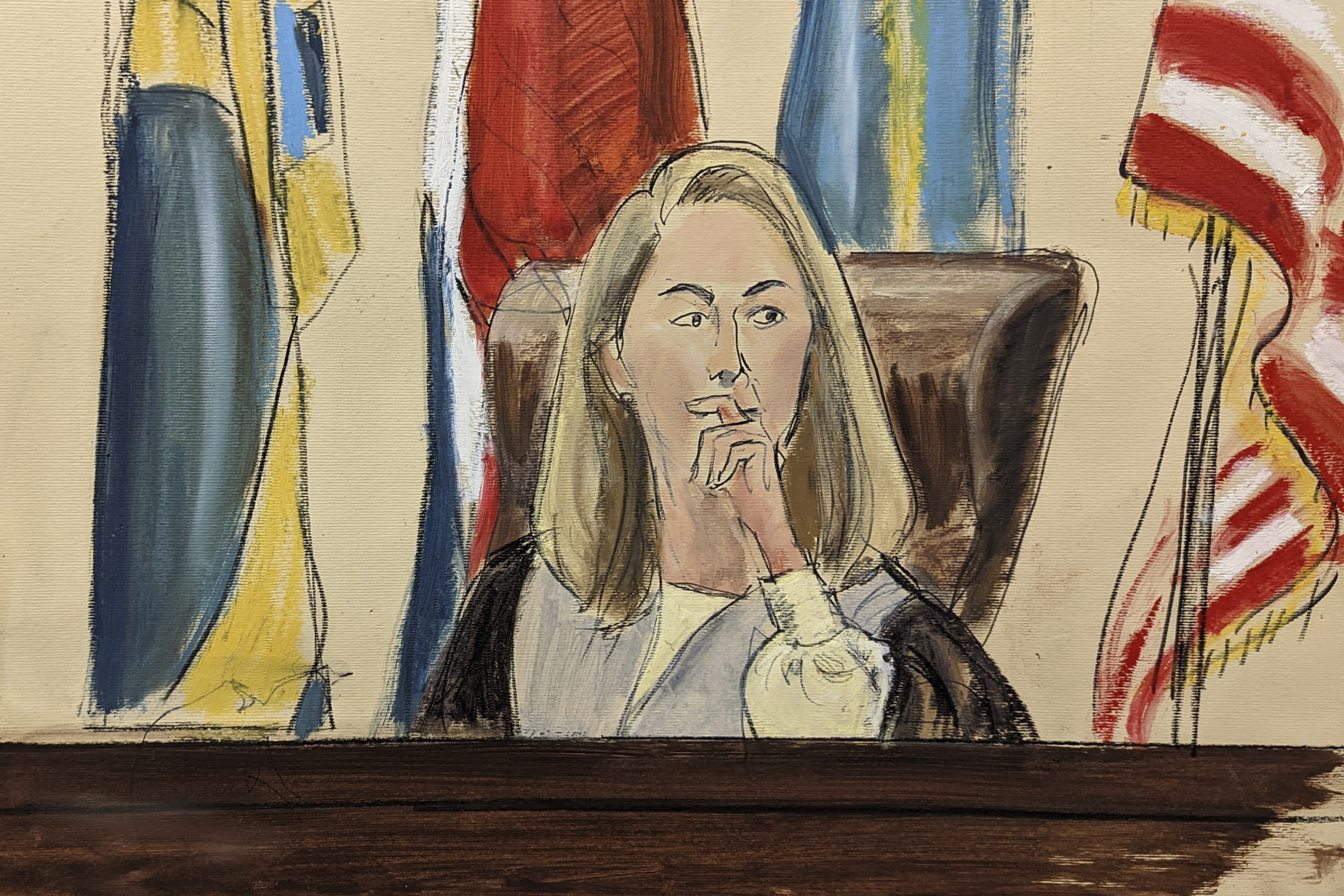

In this courtroom sketch, Chancery Court Chief Judge Kathaleen McCormick listens to testimony in a Wilmington, Delaware, courtroom on Nov. 14, 2022, where Tesla shareholders are challenging a compensation plan for CEO Elon Musk potentially worth more than $55 billion. (Elizabeth Williams via AP)

Few people in the world have the power to order around Elon Musk. One of them is a soft-spoken, small-town-raised, 44-year-old Delaware judge named Kathaleen McCormick.

When the planet’s richest person tried to back out of buying Twitter in 2022, it was McCormick who stood in the way, taking a no-nonsense approach to a lawsuit that ended with Musk backing down and completing the deal. And last month, it was McCormick who issued a landmark ruling against Musk in a Tesla shareholder lawsuit that could end up costing him some $50 billion and the title as the world’s richest person.

The decision, which found that Musk’s control over Tesla’s board led it to grant him an unfairly lavish compensation deal, left Musk fuming. “Never incorporate your company in the state of Delaware,” he posted on X, before pledging to hold a vote of Tesla shareholders on moving the company’s incorporation to Texas. The case is ongoing, with the two sides set to wrangle next over attorneys’ fees before a likely appeal to the Delaware Supreme Court later this year.

While Tesla has yet to hold a shareholder vote, Musk announced Tuesday that he has filed to move the incorporation of his privately held space company, SpaceX, from Delaware to Texas.

In her three years since becoming the first woman to lead Delaware’s influential Court of Chancery, McCormick has quickly established herself as a force to be reckoned with in the high-stakes realm of corporate litigation, insiders say. At a time when multibillionaires like Musk seem to face few checks on their power, McCormick’s sharply written opinions have sent a message: Don’t mess with Delaware.

“The reason Elon Musk frequently escapes account from other judges is because they don’t see through his phantabulating,” said Lauren Pringle, editor of the Chancery Daily, a legal publication that covers the Delaware courts. “They get wrapped up and starstruck. Not McCormick. She is clear-eyed as ever, and willing to take the slings and arrows that she knows will come with making a tough ruling.”

Those slings and arrows now include a campaign by Musk to chip away at Delaware’s special status in the corporate world. But even with 172 million followers on X and demigod status in certain business circles, Musk likely will face a battle to persuade Tesla’s shareholders to relocate the company’s incorporation—let alone convince other companies to follow its lead.

“I don’t see it getting serious traction,” Lawrence Hamermesh, professor emeritus at Widener University Delaware Law School and an expert on the state’s legal system, said of the call for companies to abandon Delaware. “He’s sort of a one-off.”

With a majority of Fortune 500 companies incorporated in the state, Delaware has enjoyed decades of dominance in the realm of corporate litigation, thanks in part to a unique court system that puts decisions in the hands of judges rather than juries. The state’s chancery court prides itself on dealing swiftly and predictably with all manner of corporate litigation.

Taxes from those corporations make up a sizable portion of Delaware’s state budget, adding to the pressure on its courts to maintain the state’s business-friendly reputation.

“One description is they sell corporate law as a product,” said Edward Rock, a law professor at New York University, referencing a coinage by the legal scholar Roberta Romano. “They market it, they care about it, they keep it up to date.”

For decades, the face of that product in Delaware tended to be old, white and male. Now it’s McCormick, a native of sleepy Smyrna, Delaware—population 13,000—who has ascended to the pinnacle of the corporate law world.

The daughter of Irish Catholic public high school teachers, McCormick underwent spinal fusion surgery at age 15 for scoliosis, but that didn’t stop her from playing softball and running track. An academic standout, she was the rare Smyrna High student to attend Harvard, where she majored in philosophy—and constructed an elaborate dorm-room bar that was the envy of her hallmates.

McCormick has always been tough, her older brother, Sean McCormick, said at a 2019 ceremony in which she was sworn in as vice chancellor. “Kate does not suffer fools,” he said. “Do not be one. If you are, she might call you names that her brothers called her when they were helping her build her character.”

After law school at Notre Dame, she returned to Delaware to start a family and her career at a legal aid foundation, which isn’t the typical launchpad for a future Chancery Court judge.

“You do public interest law, and you actually have real people whose future depends on what the court does,” Rock said, including cases involving evictions. “When you’ve dealt with real problems like that, there’s a sense, it seems to me, that you’re not intimidated by the kind of things that corporate litigators fight about.”

In a move motivated by family and personal considerations, McCormick left the nonprofit sector to become a corporate litigator at Young, Conaway, Stargatt & Taylor in Wilmington, Delaware, before being appointed to the court by Gov. John Carney (D) as a vice chancellor in 2018 and then chancellor in 2021. She took charge of a docket loaded with high-profile lawsuits.

When Twitter sued Musk in 2022 over his attempt to back out of buying the company for $44 billion, McCormick assigned herself the case rather than delegating what was sure to be a contentious, high-profile matter to one of her vice chancellors.

She was quick to put her stamp on the proceedings, rebuffing requests from Musk’s lawyers to delay the trial so they could investigate whether Twitter hid evidence from Musk about the prevalence of bots on the platform. “We’ll never know, right? Because the diligence didn’t happen,” she said, referring to the due diligence Musk waived by agreeing to the deal.

With the trial looming, Musk opted to go through with the purchase.

McCormick also presided over a lawsuit brought by a Tesla shareholder alleging that Musk’s 2018 compensation package, which reached a world record value of nearly $56 billion in performance-based stock grants, was unduly generous. Lawyers for the plaintiff, Richard Tornetta, argued that Musk himself controlled the process by which Tesla’s board arrived at the deal, and that the board failed in its duty to fully inform shareholders before a vote to approve it. (In the vote, 73% of the shares represented at the meeting approved the deal; Musk and his brother Kimbal Musk, a board member, were ineligible to vote their shares.)

Musk’s lawyers countered that the board had followed appropriate procedures and that Musk’s pay only ended up being so lavish because his phenomenal leadership propelled the company’s stock to improbable heights, resulting in huge returns for shareholders.

In a factually detailed 200-page opinion, which McCormick leavened with her trademark puns, she concluded that Musk had effectively set his own terms, enriching himself more than necessary at the expense of other shareholders, and that the appropriate remedy was to nullify the pay package altogether. In talks with the board over his pay, McCormick wrote, “Musk launched a self-driving process, recalibrating the speed and direction along the way as he saw fit.”

Dismissing Musk’s contention that the pay negotiations must have been thorough because they took nine months and 10 meetings, McCormick wrote, “Time spent only matters when well spent.”

McCormick’s role in the case isn’t finished yet. The plaintiffs indicated in a letter to the court Tuesday that they will seek attorneys’ fees from Tesla, which is likely to oppose paying what Pringle said could be a very large sum. Meanwhile, Musk’s side will seek a stay on McCormick’s judgment pending an appeal, which would be filed only after she has ruled on the legal fees.

Musk attorney Alex Spiro did not respond to a request for comment. Greg Varallo, co-lead counsel for the plaintiffs, said he expects Musk to appeal. But he scoffed at the idea that Delaware’s reputation will suffer from McCormick’s ruling.

“Investors in Delaware companies should be cheering this result and insisting that companies incorporate and stay incorporated in Delaware,” he said. “Because the court has shown once again that it is there to protect investors against overreaching controllers.”

Musk and Tesla will also have to decide when and how to follow through on his intention to relocate Tesla’s incorporation from Delaware to Texas, where Musk lives and the company is headquartered. To do so will require another shareholder vote, whose outcome is uncertain.

Five corporate law experts said that while reasonable people could disagree on aspects of McCormick’s opinion, it was well-reasoned and appeared generally consistent with precedent. Given that, all five agreed that the ruling was unlikely to elicit the outrage from the rest of the corporate world that it did from Musk.

“I don’t expect a mass migration of firms from Delaware,” said Michal Barzuza, a law professor at the University of Virginia who specializes in corporate governance. The state’s judicial expertise and large body of case law, she said, make for a relatively predictable legal environment, which most companies—and the lawyers and investors who advise them—tend to prefer.

If anything, Barzuza said, the biggest knock on Delaware’s system over the years has been that it’s too friendly to corporations; the Chancery Court previously sided with Musk in a shareholder lawsuit challenging Tesla’s $2.6 billion acquisition of the solar panel company SolarCity. But she said she does worry that states such as Nevada might put pressure on Delaware’s courts by trying to lure companies with even more lax systems that make it harder to hold directors and officers to account.

Still, Pringle said she doubts many firms will be eager to make a switch. “Uncharted waters are not lawyers’ favorite places to swim, generally speaking. No general counsel in their right mind is going to recommend that the company ‘wing it’ in a state with very little case law.”

Faiz Siddiqui contributed to this report.

Write a letter to the editor, share a story tip or update, or report an error.