Ketanji Brown Jackson gives readers a tour of her meteoric rise

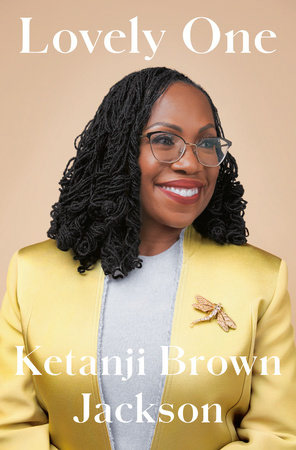

Although it offers a wealth of biographical detail, Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson's new memoir, "Lovely One," showcases little of the feistiness that marks Jackson’s judicial pronouncements. (Random House)

It hasn’t taken Supreme Court Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson long to emerge as a uniquely powerful judicial voice: Her written opinions display a rare blend of intellect and moral clarity, joined with common sense and compassion. As a district court judge in 2019, for instance, she offered a blistering rebuke to the Trump administration’s claims that White House officials could not be compelled to respond to congressional subpoenas. “Presidents are not kings,” she wrote. “[They] do not have subjects, bound by loyalty or blood, whose destiny they are entitled to control. Rather, in this land of liberty, it is indisputable that … employees of the White House work for the People of the United States.”

When the Supreme Court ended race-based affirmative action in college admissions, Jackson offered a similarly scathing dissent. By rejecting the validity of a holistic, race-conscious admissions process, she wrote, the Supreme Court “launche[d], in effect, a dismally misinformed sociological experiment,” requiring colleges to willfully disregard the ways in which race may have constrained an individual applicant’s opportunities. This “perverse, ahistorical, and counterproductive outcome … is truly a tragedy for us all.”

Sometimes, her judicial writing displays flashes of wry humor. In another 2023 dissent, Jackson poked fun at the majority’s logic: The court’s majority, she noted, seemed to assume that “because the pro-arbitration party” in the case “gets an interlocutory appeal, it should also get an automatic stay. See L. Numeroff, If You Give a Mouse a Cookie (1985).” This sly reference is not to a jurisprudential classic but to a children’s picture book (one in which a boy’s decision to offer a cookie to a passing mouse triggers a cascade of increasingly absurd consequences).

All this might lead readers to assume that Jackson’s new memoir, Lovely One, will be characterized by similar take-no-prisoners sharpness. If so, they may be disappointed. Although it offers a wealth of biographical detail, Lovely One showcases little of the feistiness that marks Jackson’s judicial pronouncements.

Instead, Lovely One introduces us to a more wide-eyed and earnest Ketanji Brown Jackson, as she grew from a serious-minded little girl, eager to earn her parents’ approval, to a hardworking young woman determined to overcome every challenge. A self-proclaimed “risk-averse rule follower,” she describes herself as someone whose “nature was to seek harmony and cooperation wherever I happened to be.”

In many ways, Jackson’s upbringing was marked by the truest kind of privilege: Her parents were educated, stable and loving, and they dedicated themselves to ensuring that their firstborn child—whose West African-inspired name, Ketanji, means “lovely one”—would have the character and the tools needed to blaze a meteoric trail through life. “My mother and father,” she writes, “were united in their determination to start me out in a program that they believed would nurture me culturally, foster my sense of curiosity and put me on the right path academically.”

In other ways, of course, Jackson faced challenges that cannot be understood without acknowledging the continued pervasiveness of racism. A sheltered child, 8-year-old Jackson struggled to understand her mother’s reaction when, one day, she lost track of time. Returning home after dark, she found her mother “frantically pacing … her abject terror turned to inchoate fury as I approached. … How could I have been so irresponsible, she demanded … ? Did I not understand what could befall a girl alone in the night? She did not add, especially a little Black girl in the South.”

Only later, Jackson writes, did she begin to understand that for Black children of her parents’ generation, “those rules about where … and when they were allowed to go could literally keep them alive.” Similarly, it took a conversation with a White friend in adulthood to make Jackson belatedly recognize the more subtle forms of racism that marked her childhood: an elementary school teacher, for instance, who cracked down on Black children for the same petty infractions he ignored when the children involved were White.

But Jackson makes clear that whether she recognized it as a child or not, her life was shaped by the omnipresent need to defy stereotypes by excelling at every turn—and the equally omnipresent fear that the White world would still dismiss her as inadequate. As an undergraduate at Harvard, she found it initially difficult to fully trust her future husband, who was White. Patrick’s declarations of love at first both thrilled and terrified Jackson. (“What was he up to?” she recalls wondering.) They triggered a long-suppressed memory: As a small child, she befriended a little White boy named Tommy, but the friendship ended abruptly when Tommy’s mother discovered the two playing together. “She spoke to me nicely and smiled the whole time,” recalls Jackson, but the next day, a distraught Tommy informed her that he was no longer allowed to play with her; his mother said she was “just too different.”

Such revelatory and painful anecdotes are relatively rare in Lovely One, however. For the most part, Jackson’s memoir is a determinedly upbeat chronicle of achievement. Jackson was admitted into a program for gifted children; she starred in school theater productions; she won prizes on the school speech and debate team; she got into Harvard College and then Harvard Law. She made Law Review, and the increasing diversity of its ranks reminds her that “our society is continuously striving to become a more perfect union.” After that; there was a federal court clerkship, then another, then a coveted Supreme Court clerkship—and eventually her own place on the court.

Unlike her fierce judicial opinions, Jackson’s conclusions in Lovely One hew closely to the conventions of memoirs by other luminaries. Yes, there are challenges: the impossible effort to balance career and motherhood, for instance, and the pain of watching her beloved older daughter struggle in school before being diagnosed with autism. But, she assures readers, “if you are diligent and well prepared, relentlessly optimistic, and resolute in purpose, you will be capable of creating a brilliant future for yourself. … [No] matter where we begin our journey, or the missteps we will surely make along the way, we must press forward, girded by our blessings and strengthened by our hardships.”

These are conventional sentiments, produced by an unconventional woman—but this, perhaps, is the fundamental tension that has shaped Jackson’s life. More than most, she understands the ways in which racism still constrains American society. But more than most, she also understands that this is not the end of the story: “It is true that not everyone was represented at the table when our country was being birthed. … Yet the principles of liberty and equality that the framers adopted … mean that every citizen can now enter those rooms.”

Jackson is a realist, but she’s not a cynic. She understands that when you’re the first Black woman on the Supreme Court, every fiery judicial opinion may need to be counterbalanced by an unthreatening meritocratic or patriotic cliche. But in Lovely One, she also insists that if we try hard enough, and work hard enough, we might—just maybe—manage to turn those cliches into truths.

Rosa Brooks is a law professor at Georgetown and a former senior Defense Department official under President Barack Obama. Her most recent book is Tangled Up in Blue: Policing the American City.

Sidebar

Lovely One

A memoir by Ketanji Brown Jackson

Random House. 432 pp. $35