What the Doug Jones election means for criminal justice reform

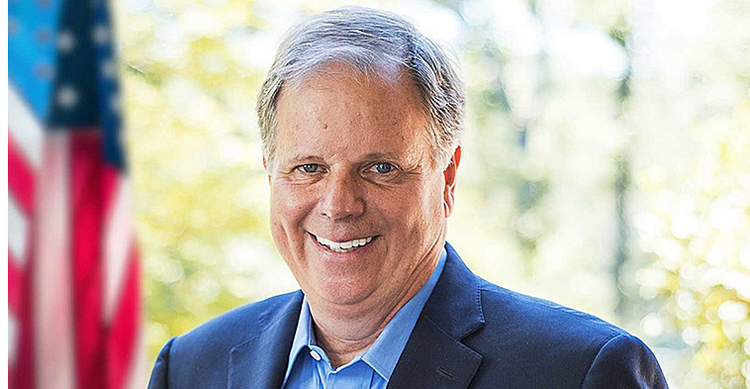

Doug Jones/Wikipedia.

Last year, prospects were looking good for a bipartisan effort in Congress to overhaul federal sentencing. But after long and careful negotiations, one senator almost single-handedly torpedoed the measure: the junior Republican from Alabama, Jeff Sessions.

Sessions, of course, went on to become Attorney General, dimming hopes even further. But Tuesday’s election of his unlikely replacement, Democrat Doug Jones, hands the seat to a former federal prosecutor who has advocated for less harsh sentencing and more alternatives to prison.

“Doug Jones was a groundbreaking voice for prosecutorial reform to end mass incarceration,” said Lauren-Brooke Eisen, senior counsel in the Brennan Center’s Justice Program. “He was one of the first prosecutors to speak out about how prosecutors can and should help reduce unnecessary incarceration.”

Jones, the former U.S. Attorney for the Northern District of Alabama, was best known as a prosecutor for securing the convictions of two former Ku Klux Klan members in the infamous 1963 bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, which killed four young black girls. The men were convicted in 2001 and 2002.

Over the last few years, Jones, who could not be reached for comment Wednesday after his victory, has begun to openly push for changes that would give prosecutors more leeway. He included criminal justice among his top campaign priorities, taking aim at mandatory minimum sentencing, disparities that send a disproportionate number of blacks and Latinos to prison, and “three strikes” laws.

“These are bipartisan issues Democrats and Republicans agree on,” Jones told a group of Alabama State University students last month. “Try to reduce the crime, keep our communities safer and at the same time cut down the costs of the criminal justice system.”

In March 2015, Jones wrote an op-ed criticizing Alabama state prosecutors who left Anthony Ray Hinton, convicted of two murders, on death row for 15 years “despite compelling evidence of innocence.”

“All of us are at risk if prosecutors believe their commitment is not to fairness and reliability but to win and defend convictions at all costs,” Jones wrote.

It’s too soon to tell what Jones’ election means for federal sentencing reform. Progress stalled under President Donald Trump, and Sessions has stayed true to his law-and-order roots, calling on U.S. Attorneys to seek the highest possible charges and rolling back a guideline that had allowed prosecutors to ignore some drug charges. Legislators and advocates instead have focused on trying to create more re-entry programs, prison educational opportunities and job skills training.

But Jones’ election elevates one of the effort’s most vocal supporters.

Two years ago, Jones and another former federal prosecutor, James E. Johnson, and other law enforcement officials formed Law Enforcement Leaders To Reduce Crime & Incarceration, a bipartisan, reform-minded advocacy group. Jones was among members who signed a letter supporting the effort that ultimately died in Congress. One of the bill’s sponsors, Senate Judiciary Committee Chairman Chuck Grassley, R-Iowa, and Republican Sen. Mike Lee of Utah, spoke at a group meeting in February 2016.

“While I sought harsh punishments for violent offenders as U.S. attorney, not all cases require severe sentences,” Jones wrote on his website. “Judges and prosecutors should be given flexibility and be empowered to decide the fate of those before them in the justice system.”

On a tour of civil rights landmarks with his daughter early last year, Johnson said he called Jones when he arrived in Birmingham and told him they were on their way to see the 16th Street Baptist Church. Jones hurried over.

In a navy suit and yellow tie, with sunglasses slung around his neck, Jones pointed to the building’s brick wall as he walked Johnson and his daughter Abigail through the evidence used to convict the Klansman bombers.

By the end of the tour, as Jones shared more about a commitment to civil rights that dated back to high school, Johnson said he felt strongly about one thing. “He is committed to right some of the wrongs of Birmingham’s past and our nation’s past,” Johnson said.

Additional reporting by Donovan X. Ramsey

This article was originally published by The Marshall Project, a nonprofit news organization covering the U.S. criminal justice system. Sign up for their newsletter, or follow The Marshall Project on Facebook or Twitter.

Write a letter to the editor, share a story tip or update, or report an error.