What privacy threats do consumers face by using internet-connected devices?

Every panelist at the ABA Annual Meeting’s “Knock Knock. Who’s There? The Internet of Things” had a favorite internet-connected device that made their lives a bit easier. Those favorites included wearable step counters, home security devices and “smart cars” that permit them to lock their car remotely or check their spouse’s commute.

But the panelists, who came together Thursday morning for a CLE discussion sponsored by the ABA Section of Litigation, also had a lot of warnings about the security and liability issues created by the growth in internet-connected devices.

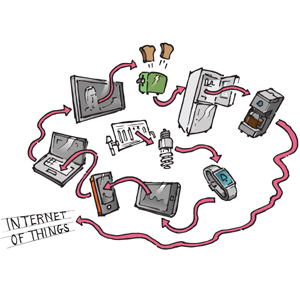

Professor Gary Marchant of the Arizona State University Sandra Day O’Connor College of Law moderated the panel. He started it off with a definition of “the internet of things”: consumer products that connect, store or transmit information to each other and to people. Amazon Echo devices and Nest brand thermostats are two examples.

The Brookings Institution predicts exponential growth in the number of those devices in the near future, Marchant said. But the most exciting thing to technologists, according to Marchant, is the connections between those devices. With a “smart” refrigerator, he said, you could easily track how soon you might run out of a staple—and maybe even order more to be delivered to your home. But that kind of setup also raises the possibility of “someone hacking your fridge and delivering 10,000 gallons of ice cream.”

Marchant first asked panelists about information privacy, a major issue when devices could be broadcasting pictures of a sleeping baby, personal health information and more. Laura Berger, an attorney for the Privacy and Identity Protection Division of the Federal Trade Commission, said consumer education is part of the answer. At the FTC, one thing regulators examine is whether information is being used in a way that consumers expect—and if not, whether the company has disclosed that in a clear and conspicuous way.

Devika Kornbacher, a partner at Vinson & Elkins in Houston, added that the technology industry should come up with a standard, as it has done in areas like graphic design. Her clients want to know what they can do to avoid litigation; adherence to a standard is one way, but the industry is still young enough that it’s not clear what that standard should be.

Another solution is to hand the reins over to the end user. Sanam Saaber (PDF) is senior director of legal at technology company Box, which permits users to securely share files and collaborate on projects. At Box, she said, the company has handed over encryption keys to customers, giving Box itself no meaningful access to the data. It also stores data in different countries locally, which helps avoid the need to reconcile the many competing privacy standards in different jurisdictions.

Robert E. Anderson Jr., of Navigant Consulting, adds that a lot of problems can be avoided by actions as simple as changing a default password or installing a patch to software that needs it (and following through to ensure it works). Recently retired from a 20-year career at the FBI, Anderson now leads Navigant’s global information security practice. In those roles, he’s become very aware of all the ways malicious people can access your data.

In addition to security and privacy, the panelists discussed discovery and products liability. Kornbacher said this is “not a new ballgame, just a new inning”—that is, the internet of things merely permits creative lawyers to find new ways to litigate. She mentioned a client in the data storage business that added language to its contracts making it clear that the data is not truly under its control or possession. Saaber said the client-side encryption key does the same for Box.

Marchant added a story of his own, about a lawsuit in which discovery turned up information suggesting that a company official was having an extramarital affair. Though the information wasn’t relevant to the lawsuit, the other side used it to get a favorable settlement.

Despite the destructive potential of the internet of things, Anderson believes there’s no turning back.

“Technology is moving so quickly that there’s a cost to liberty,” he said. “The reality is that we’re so interconnected that it’ll never go back to the way it used to be.”

Follow along with our full coverage of the 2016 ABA Annual Meeting.